An Irish doctor has spoken out about the suffering that children in institutions went through in the 1950s and 60s.

Dr Fiachra Byrne said that most of the children weren’t even criminals, but were imprisoned because they were living in poverty.

Dr Byrne told thejornal.ie: “They were suffering from status offences. Despite the rhetoric of the importance of family by the Irish State – that didn’t apply to all children in Ireland, especially the ones who were put into institutions.”

One of these institutions – St Patrick’s – closed on April 7, meaning that 17-year-old offenders are now sent to Oberstown detention centre.

The Minister for Justice Frances Fitzgerald said: “St Patrick’s Institution has been the subject of much criticism by various bodies and persons involved in the area of human rights and children’s rights.

“The signing of these orders will now consign the name of St Patrick’s to the history books and is a significant and progressive step forward in the treatment of children.”

While it may be a step in the right direction, Oberstown has also had high profile issues in recent history.

In 2016, a fire broke out after inmates climbed onto the roof during a protest. In May this year, three youths escaped after assaulting staff members and cutting a hole in the perimeter fence.

Dr Byrne has called on the government to ensure that changes are made in order to avoid repeating the same issues in the future.

He says the government needs to look to the past to understand what not to do in the future.

Dr Byrne is currently researching the mental health of juveniles in custodial institutions in Ireland and England from 1850-2000.

He says that up until the 1950s, there was a considerable reluctance to child psychology, which, in hindsight, could have made life less miserable for many people involved.

The reluctance was because of the strong link between church and state, with psychology being seen as ‘subversive to Catholic morals’.

Dr Byrne said: “That changes slightly in the 1950s, we then incorporate bits of child psychology without affecting Catholicism.”

However, plenty of problems still remained. In the early 1960s 700 boys were institutionalised at Artane Industrial school.

Dr Byrne said they were: “Quite young kids with almost no offenders at all in there.

“These children were kids deprived of a normal home life and they didn’t have proper affection.”

In 1965, care for psychologically or emotionally disturbed children – known as ‘child guidance’ – finally came into practice in Ireland. (It had been used in the UK since the 1920s).

Dr Byrne said: “Psychology here was dominated by priests in the 1930s. Proper studies were not started until the late 1950, early 1960s.

“They were still very much in a Catholic framework but there were liberal elements to it. It was modernising within a context.”

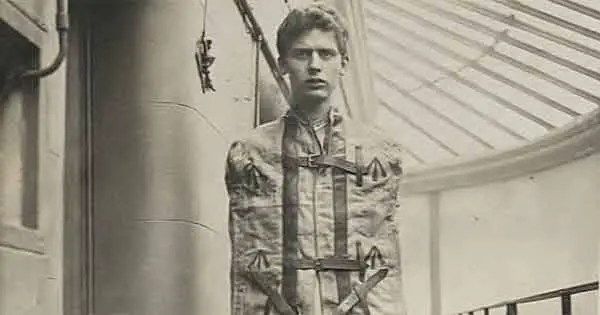

During this time, the majority of 16-17-year-old boys who were sentenced to prison in Dublin would be sent to St Patrick’s.

Dr Byrne said that the institution had very little difference to adult prisons. The boys would be forced to stay in their cells for 14 hours per day.

Punishments for bad behaviour included restricting diets to just bread and water for up to three days, solitary confinement and loss of remission.

After three days, the boy’s diet would be upgraded to porridge, potatoes, bread and water.

However, he could still be subjected to solitary confinement in a cell in a different section of the prison for up to 15 days.

They could then go another 15 days without being allowed cigarettes or even recreation time, and forced to return to their cells from 4.30pm until the following morning.

In 1971, Gabriel Slattery, who was chaplain at St Patrick’s, said that 14 hours per day in cells was a ‘considerable length of time. The psychological effects of this must be very serious especially for retarded or illiterate boys’.

He added: “The tiny window in these cells is well below ground level. The only furniture provided is a mattress, a few blankets, and a chamber pot in the corner. There is no table, no chair and no bed.

“The cell is no larger than a domestic bathroom. The removal of the mattress during the day in some cases means that a boy must sit on the wooden floor and walk around the cell for 23 hours a day for three continuous days. The 24th hour the boy spends walking in circles around the walled-in tarmac watched by an officer only and cut off from all others.”

Slattery wrote to Archbishop Charles McQuaid to describe the terrible conditions. He told how a combination of the number of boys there and the fact that one wing of the building had been ‘hacked down’ in preparation for plastering the cells had led to many being forced to stay in semi-demolished, dust-filled cells – leading to a protest by many of the inmates.

Many boys swallowed nails as part of the protest. One boy swallowed a buckle and others cut their wrists with glass.

One boy tried to burn down his cell from the inside but was saved. One inmate tried to stab another who had had tried to stop a 15-year-old boy from jumping off a balcony.

The 15-year-old said that he was terrified of being locked in his cell all night.

Similar institutions in England had begun to undergo changes in an effort to be more humane, but this didn’t start to happen in Ireland until the 1970s.

The Kennedy report in 1970 said that educational and training facilities in the institutions as ‘insufficient and primitive.’

It also said: “St Patrick’s is an old style penitentiary building with rows of cells, iron gates and iron spiral staircases. Offenders, in the main, occupy single cells. These are small and gloomy and each one has a small barred window almost at ceiling level. Offenders are held in these cells for approximately fourteen hours per day.

“The system of locking young persons into a cell alone for a good portion of the 24 hours can hardly be conducive rehabilitation. We feel that something should be done to improve conditions there.”

It was the first time that the government were recognising the issues in juvenile custody and led to new institutions being set up.

Dr Byrne said the report ‘signalled a significant disenchantment with the institutionalisation of children in Ireland’.

It also highlighted the importance of priding for the emotional and psychological needs of institutionalised children.

The conclusion of the report was that institutions that are inappropriate and inadequate should be shut down.

The ones that remain should be professionalised and that the psychological and emotional needs of the children must be met. This would include providing psychological and psychiatric assessment.

Since the report, institutions in Ireland have moved away from the church and are now more similar to those in other countries.

However, this didn’t stop the boys’ problems.

Dr Byrne said, “They started hiring social workers but some of those turned out to be sexually abusing the boys so the switch certainly didn’t solve all problems.”

He added that the institutions demonstrated systematic neglect frequently, child abuse in the past and the mistakes must never be repeated.

More popular articles and videos

The real life mystery of what Maureen O’Hara whispered to make John Wayne look so shocked

Matt Damon winning hearts and minds with charm assault on Ireland

Action hero Tom Cruise was once attacked by an old man in a Kerry pub

Liam Neeson speaks about his late wife in emotional interview

Dating site explains why Irish men make wonderful husband material

Billy Connolly says public should ignore politicians and listen to comedians

Take a look inside Hollywood star Saoirse Ronan’s stunning Irish home