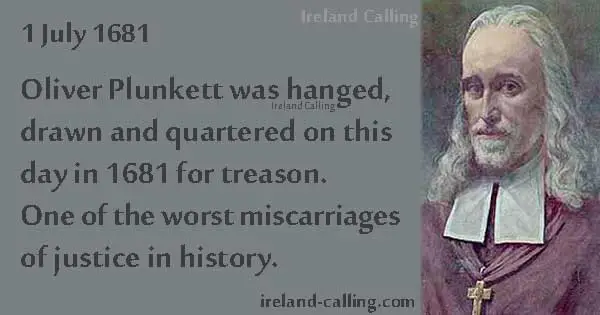

Oliver Plunkett was Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of all Ireland in the years after Oliver Cromwell had ravaged the country and the public practice of the Catholic faith was outlawed.

He was executed in 1681 due to the ‘Popish Plot’ that had nothing to do with him.

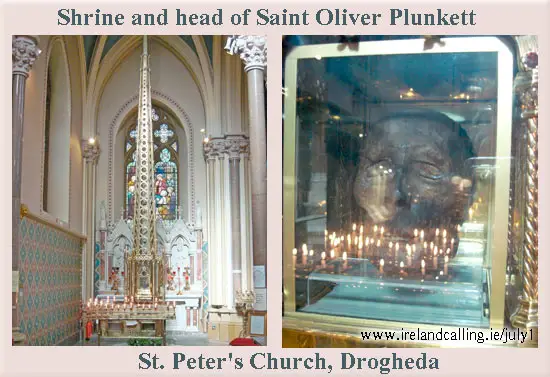

His execution has gone down as one of the most tragic miscarriages of justice in Irish and British history. He was a deeply religious man and was canonised a saint in 1975, making him the first Irish saint for nearly 700 years.

Oliver Plunkett was born on 1 November in 1625 at Loughcrew, Co Meath into a wealthy land owning family of Norman ancestry. He was highly intelligent and began his education in Dublin before moving to Rome as a teenager to continue his religious studies and became a priest.

However, at this time Oliver Cromwell and his army were invading Ireland.

Catholicism was outlawed and many Catholic priests were executed so it was unsafe for Plunkett to return. He remained in Rome and became a Professor of Theology.

He was appointed Bishop of Armagh on 9 July 1669, a position that also made him Primate of all Ireland. However, he continued to live in Rome.

Britain’s control over Ireland became more secure

In time, the hostility towards Catholics in Ireland wavered. Cromwell had successfully invaded and the British had put their own people into power.

With their position secure, many British officials in Ireland took a more relaxed approach to Catholics, and were happy to ‘leave them be’. The Restoration of the Monarchy in England had also eased the antipathy towards Catholics.

On 7 March, 1670, Plunkett returned and set up a Jesuit college in Drogheda, which welcomed both Catholics and Protestants. He also set up other schools and began working to remove drunkenness from the Catholic Church in Ireland.

He was generally left alone by British officials in Dublin, who only acted to disrupt him when ordered to do so by London.

Political smear against Plunkett

However, the tolerance was not to last. In 1673, the Test Act was passed which imposed penalties on Catholics and prevented them taking public office. It led to Plunkett’s college being closed. He had to keep a lower profile and sometimes even go into hiding.

Plunkett’s career and ultimately his life were cut short when he became the victim of a political smear campaign. In 1678, the English Protestant clergyman, Titus Oates, began circulating rumours about Catholic plots to assassinate King Charles II.

The rumours were untrue but they became known as the Popish Plot and led to widespread anti-Catholic feeling.

Arthur Capell, the first Earl of Essex, had previously held the position of Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. Capell lost his post to rival James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde.

Capell knew that Butler took a relaxed approach to the Catholic Church, and generally let them go about their business untroubled.

Capell decided to take advantage of the anti-Catholic feeling and started a totally unfounded rumour that Plunkett was planning to lead a revolution in Ireland with the support of 20,000 Frenchmen.

His aim was to discredit Butler, who would be made to look incompetent if he hadn’t noticed a rebellion being planned under his nose.

Ireland was bubbling up with revolution, with nationalist groups being formed across the country to fight back against British rule, but Plunkett wasn’t part of any of these rebel plans.

He was tried for treason in Ireland but the prosecution couldn’t get a guilty verdict as most of the witnesses were wanted men and didn’t show up in court.

The British arranged for the trial to take place in London, where it would be easier to get a jury willing to find Plunkett guilty.

Miscarriage of justice

The trial went ahead and Plunkett was found guilty and sentenced to death. It was widely understood that his death would be a huge miscarriage of justice.

Several high profile figures wrestled with their consciences, wanting to appeal for a pardon for Plunkett, but afraid they would then turn the attention on themselves.

Capell, the man who started the rumours of Plunkett planning a rebellion, realised his actions had gone too far.

He had only intended to discredit Butler and regain his place as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. He pleaded with King Charles II to spare Plunkett’s life.

Charles wanted to do so, but feared a royal pardon would provoke a political backlash from the government. When Capell asked for Charles’ help, the king reportedly raged:

“His blood be on your head – you could have saved him but would not, I would save him and dare not”

Oliver Plunkett was hanged, drawn and quartered in London on 1 July 1681. He was beatified in 1920 and canonised in 1975 by the Catholic Church. Plunkett was the first new Irish saint for almost seven hundred years.

* * *

More popular articles and videos

The real life mystery of what Maureen O’Hara whispered to make John Wayne look so shocked

Matt Damon winning hearts and minds with charm assault on Ireland

Action hero Tom Cruise was once attacked by an old man in a Kerry pub

Liam Neeson speaks about his late wife in emotional interview

Dating site explains why Irish men make wonderful husband material

Billy Connolly says public should ignore politicians and listen to comedians

Take a look inside Hollywood star Saoirse Ronan’s stunning Irish home