The Easter Rising of 1916 was one of the most important events in modern Irish history. It changed the country forever yet at first, as an event in itself, it was little more than an heroic failure.

Everything seemed against it. The rebels were ill-equipped and vastly outnumbered.

Many of them were idealists – better suited to lofty thoughts and grand ideas than to the harsh reality of fighting.

It’s likely that many of the leaders didn’t even expect to win. Both Patrick Pearse and Seán MacDiarmada had written that they may have to lay down their lives as a kind of “blood sacrifice” in order to inspire the people of Ireland to demand and achieve their freedom.

As it turned out, they may have been right, for it was the executions of Pearse, MacDiarmada and the other 14 leading figures in the Rising that created a huge change in Irish public opinion.

That seismic shift led on to the establishment of the the Irish Free State and the eventual forming of the Irish Republic.

The reasons for Irish discontent with British rule

The reasons for the Easter Rising go back hundreds of years. The Irish had never fully accepted British rule and had rebelled against it numerous times.

It wasn’t just a case of wanting independence for its own sake; the British had repeatedly given the Irish plenty of reason to rebel by their mismanagement of Irish affairs.

The most notable and tragic example was the Great Hunger, or Famine, between 1845 and 1851. More than a million Irish people died of starvation and disease following the repeated failure of the potato crop. A million more had to emigrate.

While the potato disease was a natural phenomenon, most people believed the real reason so many died was down to the greed of British landlords and the uncaring attitude of the British government in allowing shiploads of food to leave Ireland every day to be sold in England.

As far as the Irish were concerned, that was Irish food produced in Ireland and it should have stayed in the country to feed the starving.

The nationalist Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa was among the first to point out that enough food was exported from Ireland to have avoided the famine and saved hundreds of thousands of lives.

Anger at British mismanagement of the Great Hunger lingered on through the late 19th century.

There was also unrest with the way British absentee landlords were evicting poor Irish tenants from their land.

This discontent with British rule began to manifest itself in different ways. O’Donovan Rossa and others wanted full Irish inpendence and formed the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) to achieve it by force if necessary.

Michael Davitt and others formed the Land League to demand better conditions for tenants. Leading politicans like Charles Parnell led the campaign for Home Rule for Ireland.

Parnell persuaded British Prime Minister William Gladstone to introduce a Home Rule Bill in parliament but it was twice defeated by the House of Lords.

Nevertheless, the Irish Parliamentary Party kept up the pressure under the leadership of John Redmond and a Home Rule Bill was eventually passed in 1914.

Irish Home Rule did not mean Irish independence

It would be easy to confuse Irish Home Rule with Irish inpedendence but the two concepts are very different.

The Home Rule supporters from Parnell to Redmond simply wanted an Irish parliament dealing with Irish internal affairs.

They did not want to break from Britain entirely and were content to remain as part of the British Empire with Britain retaining ultimate control over matters such as foreign policy.

The nationalists, however, such as the leaders of the Easter Rising, were not interested in Home Rule; they wanted full independence.

As it turned out, the outbreak of the First World War put a stop to all talk of constitutional change.

The British government suspended Home Rule but promised that it would be introduced as soon as the war was over.

Most people at that time thought the war would only last a few months. Redmond accepted the British promise and urged that Irishmen should enlist in the British Army to fight against Germany.

The nationalists, however, had no faith in the British assurances and they weren’t interested in Home Rule anyway; they wanted full independence.

They saw Britain’s difficulty as Ireland’s opportunity. Seven men from different backgrounds began to plan a rebellion. They were Patrick Pearse, Tom Clarke, James Connolly, Sean MacDiarmada, Joseph Plunkett and Thomas MacDonagh.

They were from widely different backgrounds but were united in their belief in the need for an independent Ireland. Between them they had very little military experience.

The seven men who planned the Easter Rising

Éamonn Ceannt was an accountant with the Dublin Corporation and played uillean pipes. He was a member of the Gaelic League, which had been set up to promote Irish culture. More on Éamonn Ceannt

Tom Clarke was a veteran nationalist and one of the early members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. He had served 15 years in jail for his part in the IRB’s dynamite campaign in London. More on Tom Clarke

James Connolly was a socialist and the leader of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union. He had served in the British Army and helped to set up the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) to protect trade unionists. The ICA would also play a large part in the Easter Rising. More on James Connolly

Seán MacDiarmada was one of the IRB’s leading organisers who believed that he and other nationalists might have to offer themselves “as martyrs if nothing better can be done to preserve the Irish spirit”. More on Seán MacDiarmada

Patrick Pearse was fascinated by the Irish language and culture. He ran a school where the lessons were given in Irish and his pupils were taught to appreciate their cultural heritage. He was also a poet and a powerful speaker. More on Patrick Pearse

Thomas MacDonagh was a teacher, academic and a director of the Irish Theatre in Dublin. He only got involved in the Rising in the few weeks before it happened. More on Thomas MacDonagh

Joseph Plunkett was the highly cultured son of a papal knight. He was a poet and a director of the Hardwicke Street Theatre in Dublin. He had no military background but made a point of studying street warfare tactics. More on Joseph Plunkett

These seven men formed the Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

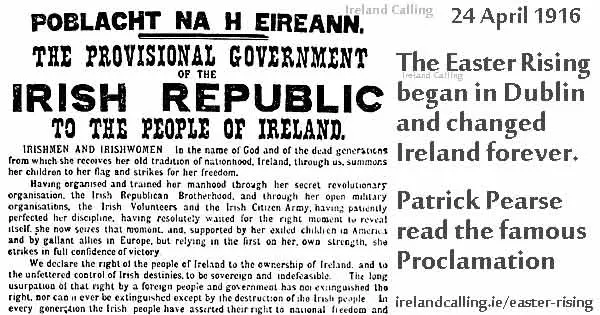

Together they planned the Easter Rising and together they signed the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, declaring themselves to be the Provisional Government of an independent Ireland.

They had little doubt that in doing so, they were probably signing their own death warrants.

The Easter Rising was unpopular with many Irish people

From our perspective today it’s easy to forget that that not everyone in Ireland in 1916 wanted to overthrow British rule and many people were unhappy about the Easter Rising.

There were several reasons for this. There were more than 200,000 Irishmen fighting for the British Army against Germany. To many of them and their families, a rebellion in Britain’s time of need was a shameful stab in the back.

A rebellion also seemed pointless to many as the British had already promised that Ireland would be granted Home Rule when the war was over. An Act of Parliament had already been passed to that effect.

For this reason, many Irish people were prepared to wait on the basis that the British would honour their pledge.

Some feared that a rebellion might do more harm than good and give the British government an excuse to renege on its promise.

The leaders understood the mood of the people but decided to go ahead anyway because they believed that their cause was just and the people would eventually come to see that.

While the rebellion was under way Pearse wrote: “When we are all wiped out, people will blame us.

In a few years they will see the meaning of what we tried to do.” His assessment turned out to be completely right.

The main groups involved in the rebellion

The troops providing the firepower in the rebellion were drawn from three main groups: the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army.

Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) The IRB grew out of the Fenian movement of the 1850s and was founded by James Stephens in 1858. It was a secret organisation dedicated to achieving Irish independence. Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa and Tom Clarke were two of its most prominent members.

It had once had about 40,000 members but this had declined to less than 2,000 as Ireland entered the 20th century. Tom Clarke set about rejuvenating it with the help of the energetic Seán MacDiarmada. The IRB remained relatively small, however, and so the leaders of the Rising intended that most of the foot soldiers would come from the Irish Volunteers. More on the Irish Republican Brotherhood

Irish Volunteers The Volunteers were formed in 1913 by Eoin MacNeill, a professor of Irish history and a member of the Gaelic League.

MacNeill was responding to the formation of the Ulster Volunteers in the North by Edward Carson. Carson wanted a paramilitary force to oppose Home Rule, which was anathema to most of the Loyalist population.

MacNeill decided it would be a good idea to have a paramilitary force with exactly the opposite objective: to support the campaign for Home Rule. More on the Irish Volunteers

The ranks of the Irish Volunteers soon swelled to nearly 190,000 men, a figure that alarmed the pacifist John Redmond. In the interest of unity, MacNeill allowed Redmond some control over the Volunteers.

Redmond used that influence to urge them to join the British war effort, safe in the knowledge that Ireland would be granted Home Rule once the war was over.

About 170,000 took his advice and enlisted in the British Army but about 11,000 refused. These would become the main military force in the Easter Rising.

Irish Citizen Army The Citizen Army was set up by the Irish Transport and General Workers Union to protect union members from police brutality during strikes and union meetings.

By 1916 it was under the control of James Connolly who planned to use it use it in the rebellion. The Citizen Army accepted female recruits and so attracted a number of women who fought in the Rising, the most famous being Countess Markievicz. More on the Irish Citizen Army

Cumann na mBhan The Irish League of Women was formed in 1914 and provided invaluable ancillary services during the Easter Rising. More on Cumann na mBhan

The leaders, the men…but where were the guns?

The seven men of the IRB Military Council planned a national rising with troops across the country taking part at the same time starting on Easter Sunday.

Due to last minute confusion that didn’t happen. The problem was that while the leaders could call on thousands of troops, for the rebellion to be successful, they also needed armaments.

The rebels hoped that Germany would be prepared to help. Sir Roger Casement was despatched to persuade the Germans to supply a shipment of arms. They duly obliged and agreed to send 20,000 rifles, 10 machine guns and accompanying ammunition.

However, the ship carrying the armaments, the Aud, was intercepted by the British off the coast of Kerry on 21 April 1916.

The German captain, Lt Karl Spindler, scuttled the ship rather than let it fall into the hands of the British and so the arms the rebels were relying upon were sent to the bottom of the sea.

Casement arrived a few days later and was arrested on Banna Strand. He was later executed for treason.

The failure of the arms to get through posed a huge problem for the Military Council.

They had some guns from a previous shipment that landed at Howth but there weren’t nearly enough to enable the rebellion to go ahead. Prominent figures outside the Military Council like Eoin MacNeill, the Chief of Staff of the Irish Volunteers, believed a rebellion should only take place if there was a reasonable chance of success, or if the British started to clamp down on nationalists and prevent them from meeting or, in the case of the Volunteers, from marching and training.

Leading figures inside the Council like Pearse and MacDiarmada were prepared to contemplate going ahead anyway in their belief in the need for a “blood sacrifice”.

In order to spur MacNeill on to action, the Military Council forged a document, supposedly from the British administration in Dublin Castle, outlining plans to restrict the activities of the nationalists. It became known as the ‘Castle document’.

MacNeill became increasingly suspicious that a rebellion was being planned behind his back and without his approval.

His suspicions were justified and when he eventually discovered that the Rising was going to ahead despite the lack of arms he was furious. His anger was compounded when he discovered that the ‘Castle document’ was a forgery.

He confronted Pearse on Easter Saturday morning and demanded that the Council called off all military action.

He went a stage further and issued an order to his Irish Volunteers which read: Volunteers completely deceived. All orders for special action are hereby cancelled, and on no account will action be taken.

MacNeill sent Volunteers across the country to make sure the message reached every unit. He also placed a similar notice in the Sunday Independent newspaper.

This presented Pearse and the rest of the Military Council with a terrible dilemma. The Irish Volunteers were providing the vast majority of the troops and without their help there was little prospect of success.

The Council held a crisis meeting at Liberty Hall, the headquarters of James Connolly’s Transport and General Workers Union.

Despite the lack of arms and the absence of most of the Volunteers, they decided to go ahead anyway. Their only compromise was to delay the start by one day until 24 April, Easter Monday.

Taking over key sites like the General Post Office (GPO)

At 12 noon on Easter Monday 1916, the leaders of the Rising and their collection of troops from the IRB, Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army assembled at Liberty Hall and set off to take control of key strategic locations in Dublin.

The people of Dublin were used to seeing them march and drill and so took little notice. Pearse and Connolly marched their men to the General Post Office (GPO) on Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street).

They attracted little attention until the order was given to take the building. Staff and customers fled as they realised the men with guns meant business and this was not just another exercise.

Pearse then read the Proclamation of the Irish Republic announcing that they were the new Provisional Government of the Irish Republic and appealing to the men and women of Ireland to lend their support.

Very few people were looking on, and most of them had little idea of what was really happening.

The rebels then set about securing the building, breaking the windows to avoid injury from splintered glass once the British started to attack.

They also built barricades on the street, and broke through to neighbouring buildings to enable them to extend their control along the street. Meanwhile, similar scenes were taking place at other locations across the city.

The insurgents were taking over other key locations including the Four Courts, the South Dublin Union, Jacob’s Factory, St Stephen’s Green, Boland’s Mills and the College of Surgeons.

These locations were chosen because they would enable the rebels to control main roads into the city.

Some, like the South Dublin Union, where Éamonn Ceannt was in command, saw fierce fighting, others such as Jacob’s Biscuit Factory were relatively quiet as the British left them largely alone while they concentrated on key targets like the GPO. More on the key sites of the Easter Rising.

The Rising lasted only six days

The Rising started on Easter Monday and was over by the following weekend. The rebels seized key buildings across Dublin but didn’t have enough soldiers to hold them because of Eoin MacNeill’s order cancelling operations.

Pearse and the other leaders had hoped that the Volunteers would rally once the rebellion began but that didn’t happen.

It’s unlikely that the outcome would have been different if they had, although the Rising may have lasted a little longer.

The remaining rebels fought bravely, but they were overcome within six days by the British Army which vastly outnumbered them and was far better equipped.

After being bombed and burnt out of the GPO, the rebel leaders retreated to a temporary headquarters on Moore Street.

Connolly had been wounded twice and was weak with pain. The decision was taken to surrender to avoid further loss of life.

Pearse asked Nurse Elizabeth O’Farrell, a member of Cumann na mBhan who had nursed the wounded in the GPO, to deliver a notice of their surrender.

As they were led to jail, the rebels were jeered by the people of Dublin who felt the Rising was ill-timed and disloyal to the 200,000 Irish soldiers who were fighting on Britain’s side during the war.

They were also angry that the rebels had created a conflict which led to the deaths of so many innocent civilians and to the destruction of so many of the city’s important buildings.

The image of the rebels in the minds of the public was diminished even further when John Redmond claimed the Rising had been organised by the Germans to undermine the British war effort.

He wrote: “Germany plotted it, Germany organised it and Germany paid for it.”

It was a completely unjustified slander but many people believed it and despised the rebels all the more because of it.

The Rising helped to create the Irish Free State

In spite of all this, the Easter Rising became a major catalyst in creating an Irish Free State and later the Irish Republic, although six counties in Ulster remained under British rule.

The reason for the Rising’s belated success was largely due to the brutal reaction of the British government once they had suppressed the rebellion.

The British sent in Lt-General Sir John Maxwell to deal with the rebels and put an end to all hopes of further insurrection.

Maxwell went about the task with great enthusiasm and was determined to send out a message that rebellion against the Crown would be ruthlessly put down.

The leaders and main protagonists of the Rising were tried by a military court. Ninety of them were found guilty of treason and sentenced to death.

They were to be executed by firing squad at Kilmainham Gaol on the outskirts of Dublin.

Pearse, MacDonagh and Clarke were executed on 3 May. Several more leaders met the same fate over the following week. As the executions continued, public opinion began to turn as people felt the punishment was too harsh.

Executions outraged Irish people

The sense of revulsion increased when Connolly was executed on 12 May. He was so weak from his wounds that he had to be tied to a chair so he would remain upright long enough for the British soldiers to take aim and shoot him.

He had been in hospital since the end of the Rising with medical staff doing everything they could to keep him alive long enough for him to face execution as a lesson to others.

Irish people who had previously had little interest in the rebellion began to express their concern and the British began to waver.

Countess Markiewicz and Éamon de Valera were also sentenced to death along with several others, but they were granted a stay of execution.

It may have been that the British were reluctant to execute a woman in the case of the Countess, or an American citizen in the case of de Valera, who was born in the United states.

But it’s also likely that they were reluctant to outrage public opinion any further with more executions, which were becoming counter productive.

The British then commuted the sentences of the rest of those found guilty of treason and they were imprisoned instead. It meant only 16 of the 90 originally sentenced to death were actually executed.

Public opinion began to galvanise around the rebels over the next few years.

The writings of people like Pearse and Connolly and others became more widely read and people began to realise that contrary to Redmond’s spurious allegations, the leaders of the Rising and their followers had been patriots and idealists, not puppets of the Germans.

The desire for Irish self-determination grew stronger and it reached far beyond a few rebel extremists.

The Easter Rising had brought a change to Ireland and there was a growing sense that the will of the people could not be denied.

It was for this reason that W B Yeats in his poem Easter 1916 composed that now famous line, A terrible beauty is born.

Ireland achieves partial independence

Sinn Fein, the nationalist party founded by Arthur Griffith, were thought by the British to be behind the Rising. In fact, they had nothing to do with it, although they became its main political beneficiaries.

They won a resounding victory in the 1918 General Election after putting forward a manifesto saying they would not take up their seats in London if elected but would establish a new parliament in Dublin instead.

Their victory was a clear electoral mandate for Irish self-determination, but faced with opposition to Home Rule from the Loyalist North, the British government stalled. However, there was little they could do to stem the tide of Irish nationalism.

Within six years of the Easter Rising, following the War of Independence, Ireland achieved partial independence, although as part of the treaty with the British government, six counties in Ulster, where Protestant Loyalists were in the majority, remained within the UK. Elected members of the new parliament, the Dáil, also had to swear allegiance to the crown.

This compromise agreement divided nationalists with some agreeing with Michael Collins that although it wasn’t full independence, it provided them with the means to achieve independence. Others, such as Éamon de Valera, regarded it as a sell-out.

The disagreement over the terms of the treaty led to the Irish Civil War with former comrades now pitted against each other. The pro-treaty faction won and on 6 December, 1922, the Irish Free State came into being.

Some of the Easter Rising rebels didn’t live to see Ireland take those first steps towards independence but they knew the dangers at the outset and were prepared to accept the consequences.

In fact, most of them knew long before the Rising began that it had little chance of success.

They went ahead anyway because they believed that the people of Ireland needed some hope, some gesture to inspire them to achieve their desire for independence.

Pearse was also proved right when he predicted: “When we are all wiped out, people will blame us. In a few years they will see the meaning of what we tried to do.”

The people of Ireland did indeed come to see the meaning of what the rebels tried to do. Not only that, they acted upon it by supporting the nationalists in the 1918 elections and the War of Independence. It that respect, the Easter Rising was an unexpected and belated triumph.

This is just a brief overview of the Easter Rising 1916. Browse our other pages to find out more about the event that changed Irish history for ever, and get more information about the characters and the groups involved.

Irish History – quick, easy-to-read summaries

Easter Rising 1916 – six days that changed course of history

The Irish Famine – the Great Hunger