Éamonn Ceannt was one of the leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising and was in command at the South Dublin Union, which saw some of the fiercest fighting throughout the six-day conflict.

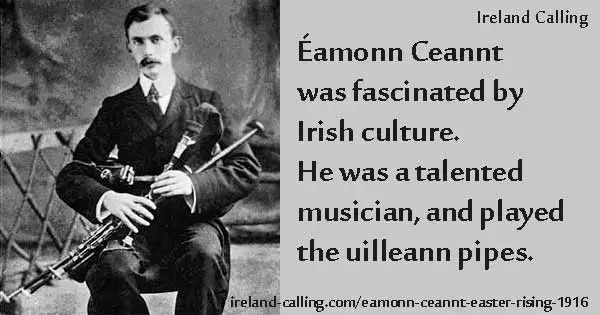

Like most of the other Rising leaders, he was fascinated by Irish culture. A talented musician, he played an uilleann pipe concert for the Pope. He was one of the seven signatories of the Proclamation of the Republic and a member of the Provisional Government.

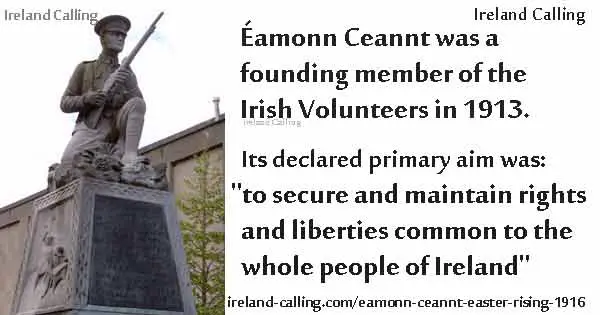

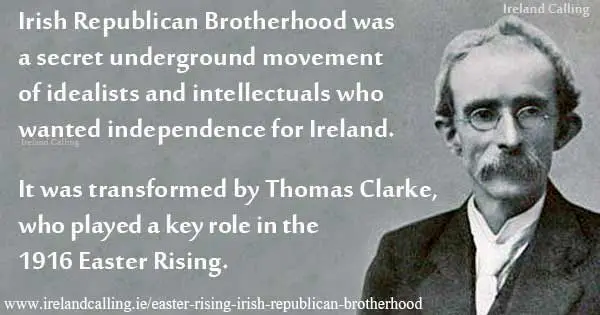

He was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and a founding member of the Irish Volunteers in 1913. He was also a member of the Military Council that planned the Easter Rising.

Ceannt was born in 1881 in Ballymoe, Glenamaddy in Co Galway. His name was originally Edward Thomas Kent but he changed it to an Irish version because he wanted to reflect his support for the Irish language and culture.

He was one of seven children and ironically perhaps, his father was in the Royal Irish Constabulary and was stationed at Ballymoe. When his father retired, the family moved to Dublin in 1892 when Ceannt was 10 years old.

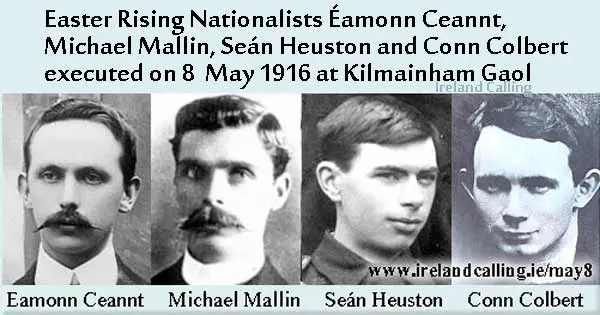

He started to attend the Christian Brothers School in North Richmond Street in Dublin, which was later attended by two other important figures from the Easter Rising, Seán Heuston and Con Colbert, who were both executed in Kilmainham Gaol.

Interest in Irish culture led him to meet leading nationalists

Ceannt proved to be an excellent pupil and did well in his final exams. He was offered a job in the civil service but turned it down as it meant he would be working for the British. Even in his teenage years, his nationalist views were already deeply ingrained. He became an accountant with the Dublin Corporation, a position he held right up until the Rising.

Ceannt was fascinated by all aspects of traditional Irish culture, which led him to become a member of the Gaelic League in 1899, a move which would later bring him into contact with leading nationalists like Patrick Pearse and Eoin MacNeill.

The Gaelic League was dedicated to promoting the Irish language and all aspects of Irish culture from history to literature, folklore, music and dancing. Ceannt acted as a teacher for the league and served on its governing body, An Coiste Gnótha, for several years. He met his wife Frances Mary O’Brennan through the Gaelic League. She too was fascinated by Irish culture. They married in 1905 and had a son, Ronan, who was born the following year.

Performing an uilleann pipe concert for the Pope

Ceannt was especially passionate about Irish traditional music and played the uillean pipes. He won a gold medal at the Oireachtas na Gaeilge festival in1906 and even played for the Pope while on a pilgrimage to Rome in 1908.

As he entered his 20s, Ceannt’s nationalist beliefs grew stronger and in 1905 he joined Sinn Féin, which had just been formed by Arthur Griffith to campaign for Irish independence. Ceannt wasn’t a socialist but wrote articles in the Sinn Féin newspaper supporting trade union leader James Connolly and his campaigns for workers’ rights.

In 1912, Ceannt was recruited into the Irish Republican Brotherhood by Seán MacDiarmada, who would also become one of the seven to sign the Proclamation. Ceannt was taking a radical step by joining the IRB because it was committed to achieving an independent Ireland and had no qualms about using to force to do it.

In 1913, he also joined the Irish Volunteers, a paramilitary army formed by Eoin MacNeill to reinforce Irish demands for Home Rule. It was also designed as a counter balance to the Ulster Volunteers who had been formed to do exactly the reverse and oppose Home Rule.

Within a year the Irish Volunteers were 160,000 strong.

On the Irish Republican Brotherhood Military Council

Ceannt soon became one the most prominent figures in the IRB and by May 1915, he was a member of its Military Council along with Tom Clarke, Sean MacDiarmada, Patrick Pearse, Joseph Plunkett, James Connolly, and Thomas MacDonagh. Together they began to plan what would become the Easter Rising in 1916.

Although the IRB, were the main driving force behind the rebellion, they were too few in number to carry it out alone.

That’s why they recruited the help of Irish Volunteers, and the Irish Citizen Army, which had been formed by James Larkin of the Transport and General Workers’ Union.

Due to last minute confusion, most of the Irish Volunteers did not take part but the IRB and about 1,200 Volunteers went ahead anyway.

Ceannt signed the Proclamation along with the six other members of the Military Council.

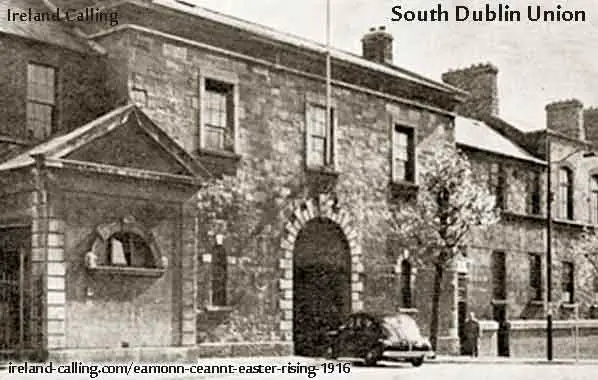

He was appointed Director of Communications of the Provisional Government and was Commandant of the Fourth Battalion of the Irish Volunteers, who were stationed at the South Dublin Union, now the site of St James’ Hospital. Ceannt had about 100 men with him, including his second-in-command Cathal Brugha, and W T Cosgrave who would later go on to become Taoiseach.

Ceannt and his men at the South Dublin Union took part in some of the fiercest fighting in the rebellion and held out against far superior numbers of British troops. They were reluctant to surrender but eventually did so when ordered by the Commander General of the Rising, Patrick Pearse.

Ironically perhaps, Ceannt’s brother William was a sergeant-major in British Army’s Royal Dublin Fusiliers, but was stationed in Cork and was not called upon during the Rising.

Executed by firing squad in Kilmainham Gaol

Éamonn Ceannt was executed, with fellow Easter Rising Nationalists Michael Mallin, Seán Heuston and Conn Colbert, by firing squad in Kilmainham Gaol on 8 May, 1916. Ceannt was aged 34.

The day before his execution, he wrote a note to his wife containing the words: “I shall die like a man for Ireland’s sake.”

He also wrote a note for other nationalists who might again strike to achieve Irish independence. It read:

“I leave for the guidance of other Irish Revolutionaries who may tread the path which I have trod this advice, never to treat with the enemy, never to surrender at his mercy, but to fight to a finish…Ireland has shown she is a nation. This generation can claim to have raised sons as brave as any that went before. And in the years to come Ireland will honour those who risked all for her honour at Easter 1916.”

Ceannt is perhaps the least well known of the signatories but his memory is still celebrated. Galway’s main rail and bus station is named after him, as is the Éamonn Ceannt Park in Dublin and Éamonn Ceannt Tower in Ballymun.

After his death, his wife Áine founded the White Cross organisation to help war victims and their families.

easter-rising-signatories.html