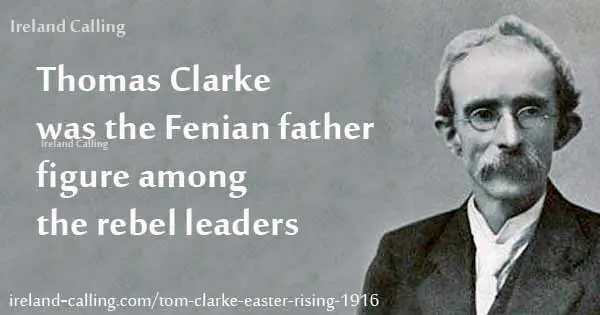

Tom Clarke was arguably the person who did the most to bring about the Easter Rising in 1916. He devoted his life to achieving independence for Ireland and spent 15 years in prison because of it.

At the age of 58, he was the Fenian father figure among the rebel leaders and was awarded the honour of being the first person to sign the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.

He was executed for his actions but died defiant with his final words being that they had put up a “grand fight, and that fight will save the soul of Ireland”.

Clarke was born on 11 March, 1858 at Milford-on-Sea in Hampshire on the south coast of England. His father was a British soldier from Co Leitrim and his mother was from Tipperary. He moved to Ireland when his parents settled in Dungannon in Co Tyrone in 1865.

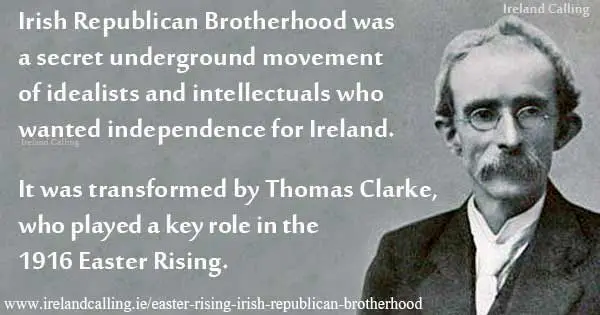

He became interested in Irish nationalism at an early age and joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) when he was 20 after being inspired by a speech by the Irish republican John Daly, the uncle of Ned Daly who was also executed for his part in the 1916 Rising.

Within a few years he was head of the IRB circle in Dungannon but had to flee to America to avoid arrest after he was involved in an attack on police. He became a friend of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, who had also been forced to flee to America because of his IRB activities.

Jailed for his part in the Fenian Dynamite Campaign

Clarke got a job as an explosives operative working on building sites on Staten Island. He put his explosives skills to use when O’Donovan Rossa sent him to London in 1883 to carry out what became known as the Dynamite Campaign.

It involved bombing key targets in the city including the Tower of London and the House of Commons.

The operation was infiltrated by the authorities after tip-offs from informers and Clarke was put under surveillance. He was captured and sentenced to life in prison on 28 May in 1983, eventually serving 15 years before he was released in 1898.

He was shocked that he had been betrayed by informers and it made him especially cautious in his future work with the IRB.

He had to serve the full term and became good friends in prison with John Daly, the man who had inspired him to join the IRB. Daly was serving a sentence for his IRB activities, including smuggling explosives.

When Clarke was released in 1998, he married Daly’s niece Kathleen. John Daly later went on to become Mayor of Limerick.

Clarke then returned to America where he renewed his friendship with O’Donovan Rossa. He kept up his links with the IRB and worked with its American sister organisation, Clan na Gael. In 1907, he returned to Ireland and opened a tobacconist shop at 75a Parnell Street in Dublin.

Reviving the Irish Republican Brotherhood

Once back home in Ireland, he worked hard to revive the IRB which was flagging by then and seemed a little tired to the new generation of nationalists.

Nevertheless, he set about trying to revive it and found willing assistants in people like Bulmer Hobson and Seán MacDiarmada (MacDermott), who held him in great esteem because his republican pedigree and his revolutionary zeal.

Together they began to rejuvenate the IRB got the membership back up to about 2,000 by 1912, a respectable enough figure for a political organisation but nothing like strong enough to stage a rebellion against the might of the British Army. Within a year, events seemed to be moving their way.

Eoin MacNeill, the O’Rahilly and others formed the Irish Volunteer Force in 1913 as a paramilitary group to fight if necessary for Irish Home Rule, which was being debated in the British parliament and facing stiff opposition from the Protestant community in the north of Ireland.

The IRB recognised immediately that the Volunteers could provide the troops they needed to stage a rebellion. Leading IRB men like MacDiarmada, Hobson and others joined the organisation with a view to steering it in their direction towards radical nationalism and rebellion.

Clarke, however, decided against joining, fearing that his conviction for the Dynamite Campaign and his well-known republican views might discredit the new Volunteer force right at the outset. Nevertheless, he kept a close watching brief and exerted influence through Hobson, MacDiarmada and Éamonn Ceannt.

One of the leading Volunteers, Patrick Pearse, then joined the IRB, increasing its influence on the Volunteers even further.

IRB was not interested in Home Rule for Ireland

There were an estimated 160,000 men in the Volunteer Force by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. By that time, Britain had passed the Government of Ireland Act, which would provide Ireland with Home Rule once the war was over.

By Home Rule they meant Ireland would have its own parliament in Dublin to govern Irish affairs. Ireland would still be part of the British Empire and Britain would still have overall control, especially for foreign affairs.

This was enough to satisfy Redmond and most of the Volunteers, who duly enlisted to fight for Britain. However, about 13,000 Volunteers refused to go.

These were the men Clarke thought could be used in a rebellion. The IRB didn’t trust the British to keep their word about Home Rule. It didn’t matter to them in any case as they didn’t want Home Rule; they wanted full independence.

Clarke’s long record of support for the IRB and nationalist causes, together with his prison record for the London Dynamite campaign, meant he was probably better known to the British authorities than most of the other leaders of the Rising. For this reason, he kept in the background as much as possible.

He was also wary of being betrayed, as he was in the Dynamite Campaign. Nevertheless, he kept working behind the scenes and was the guiding hand in much of the IRB’s activities.

Planning funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa

He made a huge contribution to the nationalist cause when he arranged the funeral of O’Donovan Rossa, who died in America in 1915. Clarke saw immediately how a funeral for such a venerated Fenian could help boost the nationalist cause, but to gain maximum effect, it needed to be held in Ireland.

As a close friend of Rossa and his family, Clarke was able to obtain the agreement of Rossa’s widow to bring back the body back to Ireland and have the funeral in Dublin.

Large meetings were banned at the time but Clarke reasoned that the authorities could hardly object if people turned out to pay their respects at a funeral.

Due to his reputation, Clarke stayed in the background as much as possible and got Thomas MacDonagh to oversee the funeral arrangements.

It turned out to be a huge event as Clarke had hoped with hundreds of thousands of people turning out to watch the funeral procession. It was a graphic display of latent Irish nationalism at that time.

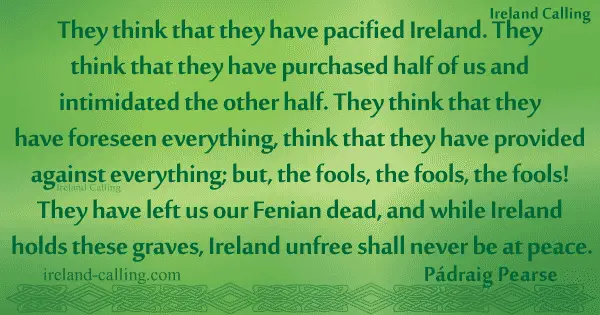

But Clarke didn’t stop at that, again wishing to remain in the background, he asked the relatively unknown Patrick Pearse to deliver the funeral oration at Glasnevin Cemetery.

‘Make it hot as hell, throw discretion to the winds’

Pearse was aware of the sensitivity of the occasion and the danger of provoking the authorities so he asked Clarke for advice on how he should set the tone of the oration. Clarke replied: “Make it hot as hell, throw discretion to the winds.”

Pearse went on to deliver one of the most memorable and powerful speeches of all time in Ireland. His closing lines have gone down in history and still resonate today: “The fools, the fools, the fools! They have left us our Fenian dead, and Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.”

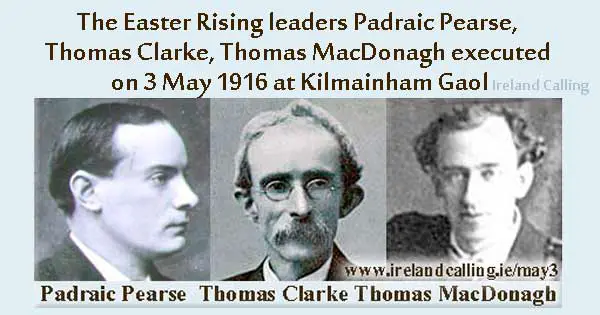

Clarke and MacDiarmada were by this time the two most effective leaders of the IRB. In 1915, they set up the Military Council to plan an uprising.

One by one over the following year another five members were appointed to the Council: Patrick Pearse, Éamonn Ceannt, Joseph Plunkett, James Connolly and Thomas MacDonagh.

They became the seven signatories of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic and members of the Provisional Government.

Clarke was the oldest signatory to the Proclamation and so was given the honour of being the first to sign. He was stationed in the GPO during the action and was executed by firing squad at Kilmainham Gaol 3 May, 1916.

‘In this belief we die happy’

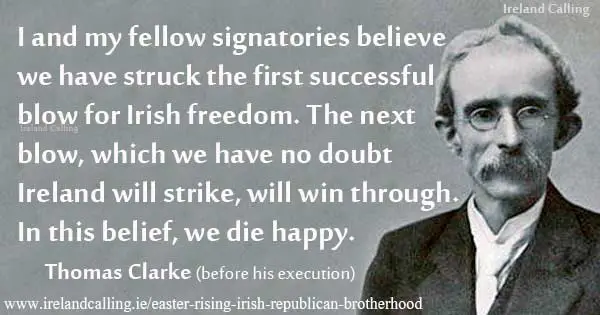

Shortly before he was executed, he gave his wife Kathleen this Message to the Irish People. It read:

“I and my fellow signatories believe we have struck the first successful blow for Irish freedom. The next blow, which we have no doubt Ireland will strike, will win through. In this belief, we die happy.”

Like the other Easter Rising leaders, Clarke has been commemorated in various ways in Ireland. He has featured on postage stamps and the Clarke Railway Station at Dundalk is named after him, as are various sports clubs and societies.

No one person alone was responsible for the 1916 Easter Rising, but Clarke did as much as any of the leaders on the Military Council and more than most to bring it about.

More history articles

The Neolithics – first people to leave their mark on Ireland