Irish children born out of wedlock in the 1950s and 60s were often sold to American couples by the Catholic Church, according to a television documentary by the author of the Philomena story.

In the BBC programme, Martin Sixsmith says that the system was a ‘lottery’ for the children as the Church did little to ensure the adoptive parents would be suitable.

Sixsmith is the author of the book Philomena, which was made into an Oscar nominated film starring Dame Judy Dench and Steve Coogan. Philomena tells the story of an Irish woman who wants to track down her son decades after she was forced to give him away by the church.

Sixsmith’s 2014 documentary, Ireland’s Lost Babies, continues to look into the subject. He speaks to several people who were adopted by American parents.

Many suffered abuse in their new families as the Catholic Welfare Bureau in the US failed to perform adequate checks on potential adoptive parents.

Sixsmith says: “The more you talk to the children who were sent out to America — and there were hundreds of them — the more you realise what a lottery the whole system was.

Some of the children had happy lives with the families they were sent to but many of them didn’t. Some of them were physically and sexually abused.”

One of those children was Mary Monaghan, who is now 63 years old.

She was adopted by Mr and Mrs O’Brien. Documents showed that the Catholic Welfare Bureau only interviewed Mrs O’Brien.

While Mrs O’Brien turned out to be a good parent, Mary was abused by Mr O’Brien.

She said: “I would be ill and I had all kinds of allergies and would break out because I was allergic to food.

“My memories are terrible. I was physically punished for not being able to eat and if I did anything like wet the bed, like a little child does, I would be put in the toilet.

The sexual abuse began very soon after that and it progressed.”

Many of the children were chosen from pictures sent to potential parents by nuns. They were often sent to America without meeting their new parents before leaving Ireland.

Cathy Deasy was another child who was adopted into this system. She remembers being photographed playing with toys so that the picture could be shown to American adopters.

She told Sixsmith: “They are what I call ‘prop shots’. The nuns took them to impress adopters. They dressed us up in nice clothes, made us pose with toys that we would never be allowed to play with, and told us to wave to the camera.”

She agreed that Sixsmith when he says: “You were literally a mail-order child. You were bought from a catalogue.”

She said: “My new parents did it all by mail. They never came to Ireland. They just told the nuns that they wanted a girl aged four or five, to be a companion for their own daughter. They sent a shopping list of what they wanted.”

She said that she had a good life in New York until her parent’s biological daughter left home and went to college.

She said: “[My sister] decided to move to California and my parents went through an empty nest syndrome and missed her so much. My father said: ‘By the way we had a college fund for you but we spent it and we intend to continue spending it and we are going on a cruise and we want you out of the house by 18.’ ”

They later sold their New York house and moved to California, eventually cutting ties with her. She said: “It was horrible to say goodbye because they were the ones who said hello to me when I got off the plane from Ireland. Even though I was supposed to be older I guess and get over it, it hurt and still hurts.”

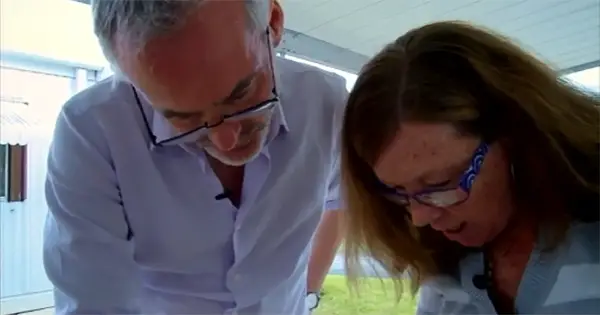

Cathy wrote to the nuns at the convent to try to track down her mother. She received a letter saying that her mother was probably dead. However, she continued searching and managed to track her down.

She told Sixsmith that she flew to Ireland to meet her. She said: “It was the happiest moment in my life. There she was, this little old lady who was my mother. She was smiling and you could see the joy in her eyes.

“I said to her, ‘I’m your daughter. I still have the same red hair’. My mother said it broke her heart that I was taken from her.

“Those were hard words to speak, but they gave me all the answers – I was never unwanted, I was never abandoned. My mother didn’t give me away.”

Thousands more children were taken against the will of their mothers during this period. The Irish government is finally considering opening up the records to help mothers and children find each other.

Philomena – tears and laughter in equal measure

Irish Woman’s heartbreaking story made into a film

Documentary on babies taken from Irish mothers by the Catholic Church