James Connolly was a trade union leader who became one of the main driving forces of the 1916 Easter Rising. His execution, for which he had to be strapped in a chair because of he was weak from being wounded in the Rising, still resonates as a powerful image in Irish nationalist circles.

He played a large part in setting up the Irish Citizen Army and became its commander. He was one of the seven signatories of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic and a member of the Provisional Government.

Connolly’s life and actions were dominated by the twin pillars of socialism and nationalism; a stance he maintained right up to his execution in Kilmainham Gaol.

Connolly’s parents were Irish from Co Monaghan but he was born in Edinburgh on 5 June, 1868 and spent his childhood in the city. He spoke with a Scottish accent all his life, but his Irish parentage and the presence of a large Irish community in a slum area known as “Little Ireland” in Edinburgh meant he developed a deep interest in Ireland from an early age. He started working at a printers in Scotland and then joined the British Army, spending most of his seven years’ service stationed in Cork.

Poverty he saw in Ireland and Scotland affected him deeply

The poverty he saw both in Scotland and Ireland affected him deeply and led to him becoming a socialist.

After finishing his military service, he married Lillie Reynolds, a Protestant from Co Wicklow and returned to Edinburgh where he met the Scottish socialist John Leslie. Leslie became a major influence on Connolly and introduced him to the work of Karl Marx. Connolly was highly intelligent but had little formal education. Marxism provided a political and economic structure to underpin his socialist instincts.

He returned to Dublin in 1896 and set up the Irish Republican Socialist Party. In one move he linked the emancipation of the working classes with the cause of Irish Independence. Soon afterwards he set up the Workers’ Republic newspaper. Neither venture was very successful at first but both enabled Connolly to refine his socialist beliefs and to start building his reputation in Ireland.

No desire for Home Rule – only independence

Connolly’s nationalism was very different to the calls for Home Rule espoused by many affluent Irish politicians and businessmen. He saw no point in the Irish working class simply swapping an exploitative British ruling class for an exploitative Irish ruling class. He wrote in the Workers’ Republic:

“The cry for a union of classes is in reality an insidious move on the part of our Irish master class to have the powers of government transferred from the hands of the English capitalist government to the hands of an Irish capitalist government and to pave the way for this change by inducing the Irish worker to abandon all hopes of bettering his own position.”

Frustrated by his lack of success in promoting socialism, Connolly emigrated to the United States where he again got involved in socialist politics and trade unionism. However, it was not until he returned to Dublin to work with trade unionist Jim Larkin that his career really began to take off.

Connolly was appointed as the organiser of the Belfast branch of Jim Larkin’s Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU).

With Jim Larkin in the Dublin Lockout 1913

He was very successful in the post but returned to Dublin in 1913 to help Larkin in the great Lockout, which saw workers shut out of their workplaces by factory owners in retaliation for having joined trade unions.

Many of the union’s meetings had been broken up by the police who were often brutal in their approach. Some members had been beaten to death by officers. Larkin and Connolly responded by setting up the Irish Citizen Army, which would protect union members from police brutality.

Larkin left Ireland for America in 1914 and Connolly became leader of the union and the Irish Citizen Army. The union’s headquarters, Liberty Hall on the banks of River Liffey, became Connolly’s power base and a centre for planning the Easter Rising. The Proclamation of the Republic was printed there, and the rebels all rallied there before setting off to their different locations on the day of the Rising.

At around this time, Connolly became increasingly convinced that independence from Britain was the only way to improve the lives of ordinary working people. He regarded the outbreak of the First World War as an ideal time to strike for Irish freedom. He soon came to the attention of Patrick Pearse and Eoin MacNeill, who were thinking along the same lines. Pearse was a leading figure in the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and MacNeill had set up the Irish Volunteers, a paramilitary group designed to add muscle to the campaign for Home Rule.

Connolly considered his own rebellion using Citizen Army

Pearse was concerned that Connolly and his Citizen Army might start a rebellion of their own. The two men met and on 19 January, 1916 Connolly entered into three days of negotiations with the IRB to plan the Easter Rising. They agreed on joint action and Connolly was appointed vice-president of the Irish Republic.

Connolly then became a member of the IRB Military Council that was planning the Rising. The others were Tom Clarke, Sean MacDiarmada, Patrick Pearse, Joseph Plunkett and Thomas MacDonagh.

Connolly’s military background and organisational skills as a trade union leader made him a natural leader and he was soon appointed Commandant-General of the Dublin Division of the Irish Army, a task he fulfilled with distinction and courage.

On Easter Monday, 24 April, he and Pearse, who was the Commander General of the Rising, led the Liberty Hall Headquarters Battalion to the General Post Office (GPO) on Sackville Street (now renamed O’Connell Street) and the Easter Rising was under way. They took over and secured the building, and Pearse stood outside and read the Proclamation of the Irish Republic to bewildered passers-by.

Connolly commanded his troops with skill, courage and concern for their safety. In the ensuing fighting, they were vastly outnumbered by the British Army yet suffered only nine fatalities. Connolly was twice wounded by sniper fire but kept organising events right up the end, even though he was in terrific pain and could receive little medical attention. Pearse noted in his journal that Connolly was “still the guiding brain of our resistance”.

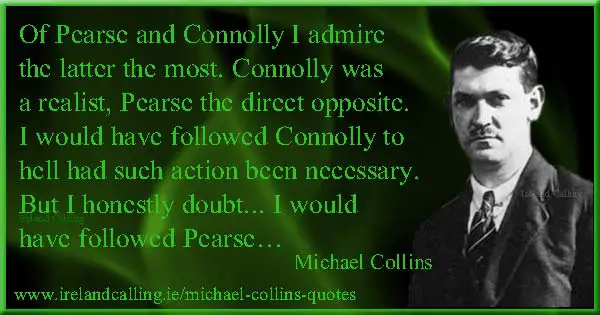

I would have followed him through hell – Michael Collins

Michael Collins, who also served in the GPO, later said of Connolly that he “would have followed him through hell”.

By Saturday 29 April, the GPO was on fire and under bombardment. The rebels retreated to nearby buildings on Moore Street but they knew they could not continue to resist. Pearse and most of the other leaders felt they had no choice but to surrender to avoid further bloodshed among the volunteers and the citizens of Dublin, who were suffering the highest number of casualties.

He agreed with the decision to surrender on the basis that he “could not bear to see his brave boys burnt to death”.

He believed that the British would only execute the leaders of the Rising and told his men: “Don’t worry. Those of us that signed the proclamation will be shot. But the rest of you will be set free.”

Pearse signed the surrender order and Connolly counter-signed on behalf of the Irish Citizen Army. He faced a court martial for treason as the British sought to purge the leaders of the Rising as a lesson to future rebels – a decision that was to backfire completely. (See public opinion and the Easter Rising)

At his trial, where execution was virtually a foregone conclusion, he read from a note he had managed to write despite his weakened state, saying: “The cause of Irish freedom is safe … as long as … Irishmen are ready to die endeavouring to win it.”

Connolly was executed by firing squad in Kilmainham Gaol on 12 May 1916. He was unable to stand because of his wounds from the fighting and had to be tied upright in a chair before the firing squad could take aim.

I will say a prayer for all men who do their duty

The priest who administered him the Last Rites asked him to pray for the soldiers about to shoot him. He replied: “I will say a prayer for all men who do their duty according to their lights.”

Connolly was the last of the leaders to be executed. By that time, the British were surprised and shaken by the public outcry against the executions both in Ireland and America. They decided to call a halt rather than risk inflaming the situation in Ireland, and alienating the Americans, whose help they needed in war against Germany.

Following his execution, his wife Lillie was accepted into the Catholic Church on 16 August, 1916.

A hundred years on and Connolly remains an iconic figure in Irish history. A statue of him was erected in his honour in 1996 outside Liberty Hall in Dublin. In tribute to his socialist and nationalist beliefs, the inscription with the statue reads: The cause of Labour is the cause of Ireland and the cause of Ireland is the cause of Labour.

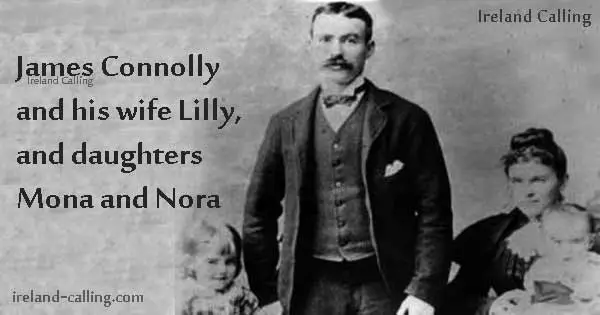

Connolly left a wife and six children

Connolly and his wife Lillie had six children together. The youngest, Roderick, was born in 1901 and served with his father in the GPO, even though he was only 15. He later formed the Communist Party of Ireland and became a Labour Party Teachta Dála (TD) for Louth.

James Connolly’s second daughter Nora Connolly O’Brien also became a prominent socialist and nationalist and served three terms in the Seanad, the Upper House of Oireachtas, the Irish Parliament.

Several members of the family still live in the Dublin area. Read about Connolly’s grandson John Connolly, who has been active in the campaign, to save Moore Street, where the rebels made their last stand and ended the Rising.

easter-rising-signatories.html