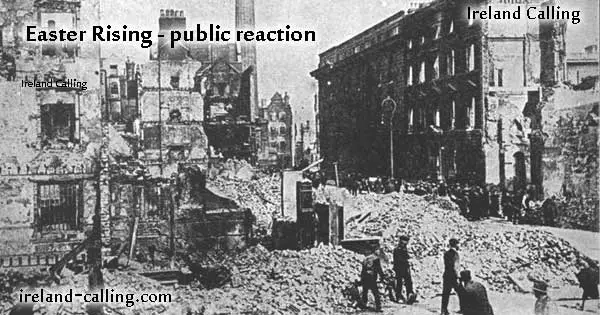

The Easter Rising of 1916 is now widely regarded with pride as the event that marked the beginning of the end of British rule in most of Ireland; at the time, however, it was very unpopular with most Irish people who were highly critical of the rebel leaders.

There are several reasons for this. Ireland had been an integral part of the United Kingdom since the Act of Union in 1801 and had been subject to varying degrees of British rule since the 12th century.

It had, of course, been an uneasy union.

There had been several rebellions against the British before the Easter Rising so the pursuit of independence was ingrained in the Irish character. The way the British had managed the Great Hunger (or Famine) also left lasting bitterness, as did the Land War in which tenant farmers had to fight and campaign for basic rights over the land they rented.

Nevertheless, by 1916 there were many people who were happy with the status quo, or at least happy enough not to consider it a major issue. There was a growing Catholic middle class who were doing well under British rule. Thousands of people were employed by British owned companies and were pleased just to have a job.

The British Army provided employment for thousands of young Irishmen who might otherwise be out of work or face the prospect of having to emigrate. There was, of course, gruelling poverty and hardship, but few people would have regarded independence as being the way to alleviate such distress and provide people with greater prosperity.

Many Irish people questioned the need for rebellion

It’s also the case that most people would have questioned the need to rebel in 1916. The British had passed the Home Rule Act in 1914 and although its implementation had to be postponed because of the outbreak of the First World War, the British Government had pledged to revive it once the war was over.

Home Rule had been the quest of the Irish Parliamentary Party since the days of Charles Parnell in the 1870s, and now it was finally coming to fruition under the leadership of John Redmond.

The Home Rule promised was not the same as independence. Britain would still have ultimate control over Ireland but there would be a parliament in Dublin passing its own laws for Ireland.

For most Irish people at that time, this was enough. They were prepared to wait until the end of the war for Home Rule to come into effect and in the meantime, they were happy to support the British war effort. In a way, they voted with their feet. The Irish Volunteers had been set up in 1913 to fight if necessary for Home Rule.

Once the First World War broke out, there was a split in the ranks. The Chief of Staff of the Volunteers Eoin MacNeill urged the Volunteers to refuse to sign up and to stay in Ireland; John Redmond urged them to enlist in the British Army. More than 100,000 Volunteers sided with Redmond and enlisted; only about 13,000 followed MacNeill’s advice and stayed.

In all, more than 200,000 soldiers went off to fight on the British side. For most of them, it was just a job, but back home in Ireland, their families supported them, worried about them and prayed for them to come home safely.

That being the case, it’s not hard to see why those families would not look kindly on a rebellion that sought to take advantage of Britain’s involvement in the war.

Indeed, if British troops had to be deployed to quell a rebellion then they were not available to provide support on the front lines in Europe and that in turn could make Irish soldiers fighting for Britain more at risk.

While many Irish citizens were sympathetic to the rebels and their cause, many others saw it as harmful, disloyal and even cowardly to try to exploit the situation when so many Irish troops were fighting abroad. This is why the rebels were jeered by many Dubliners as they were led away to prison once the Rising had been quelled.

Brutal treatment of rebels caused public outrage

Most leading Irish politicians were quick to condemn the Rising, playing to the widespread propaganda that the rebels were in league with Germany. Redmond wrote: ‘This attempted deadly blow at Home Rule is made more wicked and more insolent by the fact that Germany plotted it, Germany organised it and Germany paid for it.’

Redmond was completely wrong about this and would later have reason to regret his outburst, but at the time he was tapping into the propaganda of the day and he had some success. Ordinary people, dependent on British companies for work and having sons fighting against Germany, felt a sense of outrage. They were also angry that more than 500 innocent civilians were killed during the Rising and some of Dublin’s major buildings were destroyed.

However, public opinion can be fickle as the British were to find out. Following the Rising, the British imposed martial law on Ireland and sent Major General Sir John Maxwell as Commander-in-Chief.

He became known as ‘Bloody Maxwell’ because of his eagerness to impose the death penalty. He wanted to crush Irish nationalism once and for all by making an example of the leaders of the Rising. He held military courts and more than 90 of the rebels were sentenced to death.

Fifteen of them were executed within two weeks after perfunctory military trials. Then something remarkable happened. Public opinion began to turn. Many people who had opposed the Easter Rising were outraged by Maxwell’s ruthless approach, which they saw as a gross overreaction.

Connolly was shot while strapped to a chair

The outrage grew as the stories of the executions began to reach the public. One of the most dramatic involved the trade union leader James Connolly who had been a commander at the General Post Office.

He had been wounded by a stray bullet during the fighting and had lost a lot of blood.

When the time came for him to be executed by firing squad he was too weak to stand. Rather than delay, he was strapped upright in a chair so the soldiers could take aim and shoot.

There was also the story of Joseph Plunkett, who was executed hours after marrying his fiancée Grace Gifford in Kilmainham Gaol.

British brutality changed public opinion

Stories of this kind quickly spread and changed public opinion throughout the whole of Ireland. People who had opposed the Rising now began to sympathise with rebels. This mood was enhanced when people began to learn more about the rebel leaders and read some of their writings. It became apparent that rather than being traitors and German stooges, they were idealists who, even if they were misguided, were at least acting in what they considered to be Ireland’s best interests.

They came to be seen as people who had fought the good fight against overwhelming odds and in doing so had restored Irish national pride.

The change in public opinion quickly persuaded the British that the executions were counter-productive and were turning the rebel leaders into martyrs. The rest of the 90 facing the death penalty had their sentences commuted, except for Sir Roger Casement who was seen as an exceptional case and was hanged in Pentonville Prison on 3 August 1916.

Executions increased Irish nationalist fervour

Maxwell’s hope that the executions would set an example and intimidate the Irish backfired completely. Each execution served merely to fan the flames of nationalist fervour until it became irresistible.

In the following two years, support soared for the nationalist party Sinn Fein. It had not been involved in the Rising but now became the focal point for people wishing to break free from British rule. Sinn Fein won a landslide victory in the 1918 General Election. John Redmond’s Home Rule supporting Irish Parliamentary Party was wiped out. Sinn Fein’s victory was particularly significant because they rejected mere Home Rule and had told the electorate that if they won, they would not attend the British parliament in London but would set up an independent Irish assembly in Dublin.

That is precisely what they did on January 1919. The British refused to recognise it, sparking the Irish War of Independence (Anglo-Irish War) which ended with the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922.

The story of Irish independence still had a long way to go but the first major step had been taken, and the Easter Rising had been the catalyst that moved public opinion.

Maxwell realised that he may have won the war against the rebels but through the brutality of the executions, he had effectively lost the peace. Instead of extinguishing the flame of Irish nationalism, Maxwell merely made it burn more strongly.

For this reason, he came to be seen as the man who lost Ireland for the British.

How the British struck back at the Easter Rising rebels