I’d started feeling a little queasy as soon as I sat down and buckled my seatbelt. Now, as the plane rumbles down the runway and starts surging skywards, my temperature’s also soaring and my stomach’s beginning to churn.

Thankfully, rather than reaching for a sick bag, I simply whip off the headset I’ve been wearing and the nausea quickly settles.

I’m back on solid ground, in a quiet room in an office in central London to be exact – and this is precisely where I’ve been all along.

The aeroplane taking off was virtual reality (hence the headset). Minutes earlier, I’d been standing on the roof of a skyscraper, even leaning over the edge to look at the tiny cars on the streets below. Then I’d ventured into a dusty attic and watched as sizeable spiders scuttled towards me, before finding myself in a hospital waiting room and being ushered into a cubicle for an injection – all while comfortably sat in the same office chair, headset in place.

Virtual reality (VR) is not new, of course. But developments in technology mean the possibilities and quality are ever improving and VR has become a bit of a buzzword again, particularly in gaming.

Senior therapist Michael Carthy believes it has huge potential in treating phobias and anxiety, too. “Our senses are easily fooled. The unconscious cannot tell the difference between real and fake; reality or fantasy,” he explains.

Same but different

Exposure has long formed the basis of a number of phobia treatments. Perhaps you’ve heard of Immersion Therapy or ‘flooding’, where people are gradually encouraged to encounter the scenario they’re afraid of, with the idea being that they will re-learn or alter their responses to it along the way.

Carthy says this process can happen much faster with VR – which could be a bonus in itself, as well as potentially being far cheaper than going down a more traditional therapy route (he says just three or four sessions may be required for “rapid and permanent change”). Plus, for people with phobias or anxieties so severe they routinely impact their behaviour, choices and, as such, their quality of life, even the idea of confronting the subject of their fears in a therapeutic setting can be too daunting. VR might be a ‘safe’ option. You get the benefits of the therapy and ‘facing’ your fears, but you know you’re not ‘really’ putting yourself at threat, because it’s all on a tiny video screen. But if that’s the case, does it actually work?

Real fear

Carthy is confident that it does, which is why he’s founded VRealityTherapy, London’s first ever VR therapy (VRT) clinic, which has just begun welcoming clients from across the UK.

VRT actually dates back to the early Nineties and since then, numerous studies have demonstrated its effectiveness, with some even finding it outperforms other, more traditional, treatment approaches.

For Carthy – with his background in Applied Positive Psychology and almost a decade’s experience helping thousands of clients overcome phobias and anxiety, along with being a bit of a self-confessed gamer and tech-fiend – it’s a natural fit.

It might be virtual reality, he explains, but that makes no difference to our fear responses. In other words, although we know it’s not real, the crucial parts of our brains still perceive it as real and respond as such – which enables a therapist to create a suitable environment in which to begin addressing those phobic reactions, usually through techniques incorporating cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) principles.

“Case in point: sitting in the cinema watching a horror movie and feeling petrified, or screaming and shouting at Game Of Thrones on TV. This feels real to us, but it’s a fantasy.” he says. “The fantasy’s created out of thin air and involves painstaking production, images are captured that make our senses feel something, and projected through a device for us to experience. The mind cares about experience. And an experience is what it is, either real or imagined or produced. In a way, there are no fake experiences.”

Real evidence

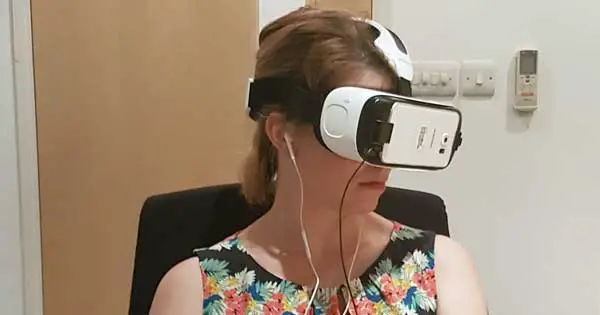

To demonstrate, before I put on the VR headset to ‘experience’ some of the phobia therapy settings, Carthy hooks me up to some bio-metric monitors, to capture physiological responses that indicate whether I’m having any fear or nervous reactions.

I’m a little bit sceptical, thinking I probably won’t be fooled into actually getting scared while, for example, peering over that virtual ledge hundreds of storeys above the ground.

The graphs Carthy shows me afterwards, however, prove otherwise. At the scariest points, there are indeed indications – like an elevated heart rate – that my brain and body were registering real fear. As for the flying episode; I’m not afraid of flying, but I do get travel sickness every now and then, and I certainly didn’t need a bio-metric report to tell me I’d come pretty close to throwing up!

newsletter.html”]