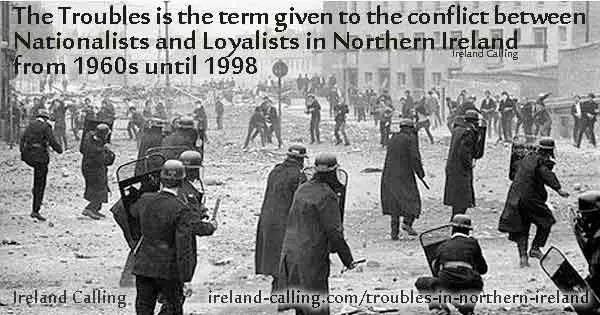

The Troubles is the term given to the conflict between Nationalists and Loyalists in Northern Ireland from the 1960s onwards until 1998. The conflict was sparked by the demand for civil rights and ended when the Good Friday Agreement led to a new power sharing government involving representatives from both sides of the community.

During those four decades of civil strife, which is sometimes referred to as the Northern Ireland Conflict, more than 3,500 people were killed and thousands more were injured. More than 1,800 of those killed were civilians. The other casualties included police, British soldiers, and paramilitaries from both the Nationalist and Loyalist sides.

Although the conflict saw Catholic pitted against Protestant, it wasn’t essentially about religion. It was rather that the political leaning of the Catholics was largely (though not exclusively) Irish Nationalist, while the Protestants overwhelmingly saw themselves as British and loyal to the British crown.

The reason for this deep division dated all the way back to the early 17th century.

Background to the Troubles – the Plantation of Ulster

The British monarchy had tried for centuries to control Ireland since the days of the Anglo-Norman invasions in the 12th century. They never managed it and were faced with numerous rebellions.

After some decisive victories over the Irish lords in the early 17th century, James I of England tried to solve the problem once and for all by moving the Catholic Irish off their lands and replacing them with Protestant settlers from England and Scotland.

The majority of these settlers were sent to the most rebellious counties in the north in a move that became known as the Plantation of Ulster. These settlers soon outnumbered the indigenous Irish in parts of the province but were a minority in Ireland as a whole. They knew they were resented and faced a constant threat from the displaced Irish.

They relied on Britain for protection and so became fiercely loyal to the British Crown. This gave rise to the term Loyalist as a way of describing them.

Unlike English settlers in previous centuries, the Loyalists never integrated into Irish society and never adapted to Irish ways. They saw themselves as a group apart and developed a siege mentality. This attitude took on a literal element in 1688 when the Protestant community in Derry came under siege from the Catholic King James II who was trying to claim the English throne.

The siege was broken by the Protestant William of Orange who later went on to defeat James at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690.

The Loyalists were jubilant and adopted the colour orange as a symbol of their loyalty to William and the British Crown.

Loyalists and the fight for Irish independence

The Loyalists remained as a group apart until matters came to a head in the early 20th century when Home Rule for Ireland became a major issue.

The Nationalist fight for self-determination led to the Irish War of Independence between 1919 and 1921. It ended with a truce and negotiations began to provide Ireland with a form of independence that was acceptable to both the Irish and the British. The Loyalists in the North reacted furiously to the suggestion, fearing that they would be swallowed up in a hostile, Catholic Ireland.

They had earlier formed a militia called the Ulster Volunteers and threatened to oppose Home Rule by force if necessary. Eventually, the British, the Loyalists and the Irish Nationalists reached an uneasy compromise that meant most of Ireland would gain partial independence and have a parliament in Dublin, but the six counties of Ulster that contained large Loyalist majorities would have their own separate parliament and remain part of the United Kingdom.

It was an uneasy compromise that pleased no one, least of all the Catholic minority in the six counties, but in the end it passed into law with the Government of Ireland Act of 1920. The Act created a new parliament for the new state to be known as Northern Ireland. Unlike Scotland and Wales, Northern Ireland was never known as a country. The new parliament was based in Belfast and quickly became known as Stormont because it was situated in Stormont Castle.

The Act recognised that the Catholic minority would always be outvoted in the state elections to the new parliament so it introduced proportional representation, to ensure that the Catholics would at least have some voice in government.

The Loyalist dominated Stormont government

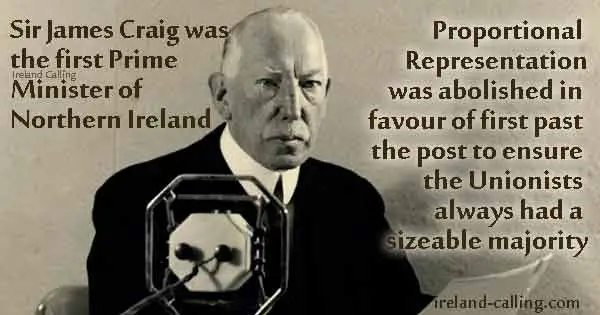

The first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland was Sir James Craig of the Ulster Unionist Party. Craig was a committed Loyalist who from the outset described Stormont as a Protestant parliament for Protestant people. Over the next 40 years, Craig and his successors set about ensuring that the Unionists always had a stranglehold on power in Northern Ireland.

Proportional Representation was abolished in favour of first past the post to ensure the Unionists always had a sizeable majority. Electoral boundaries were redrawn in a process known as gerrymandering to make Unionist electoral domination even more unassailable. This policy was so successful that even areas with Catholic majorities such as Derry would return Unionist representatives.

The electoral system meant only ratepayers and their wives could vote in local council elections. Adults who lived with parents and so didn’t pay rates were disenfranchised. As Catholics were more likely to be unemployed and so dependent on their parents, this too helped Unionists to retain electoral power.

The Unionist position was further bolstered by the police force, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) which was more than 90% Protestant even though Catholics made up more than 30% of the population.

By the late 1950s, the Unionists controlled every aspect of Northern Ireland and ran it to benefit their own community to the detriment of Catholics. The Protestant Loyalists had the best housing, were more prosperous and had the best job prospects.

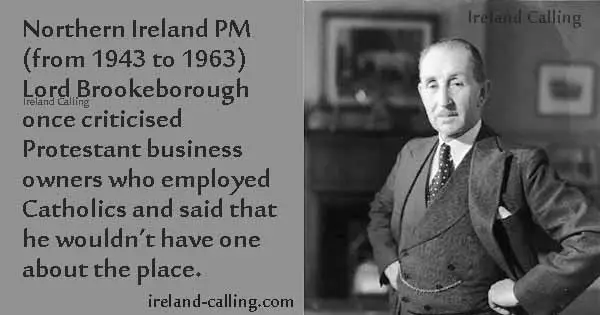

Another Northern Ireland Prime Minister, Lord Brookeborough once criticised Protestant business owners who employed Catholics and said that he wouldn’t have one about the place.

The Catholic minority became increasingly isolated and powerless. They had no political influence in their own state and they got very little support from the recently formed Republic of Ireland, which although it still laid claim to the North, showed little interest in doing anything about it.

It meant that by the beginning of the 1960s, the Unionists controlled all the arms of government, got all the best jobs, all the best housing and all the best opportunities. The Catholic minority were treated as second class citizens.

1960s and the Civil Rights Movement in Northern Ireland

The world, however, was changing and Northern Ireland could not stay isolated forever. In the United States, the civil rights movement was making waves that quickly crossed the Atlantic to Ireland. A new generation was emerging in Northern Ireland, better educated following the passing of the Education Act by the Labour government in Britain.

Young Catholics of the Beatles generation were not prepared to suffer the injustices and the lack of prospects endured by their parents. They wanted reform so that they could enjoy the same rights and opportunities as their Protestant neighbours.

By the mid-sixties, many Unionists agreed that change was necessary. The most prominent of these was Captain Terence O’Neill.

Terence O’Neill and early attempts at reform

In 1963, the diehard, old school Loyalist Lord Brookeborough resigned and was replaced as Northern Ireland Prime Minister by Captain Terence O’Neill… a very different kind of leader.

O’Neill was an Eton educated former officer with the Irish Guards. He had an English accent and was never truly accepted by some of the more extreme Loyalists as being one of them and being totally for them. He was soon to give them cause for concern.

O’Neill was from a new generation and he knew that the old ways of total Unionist domination could not continue. Between 1963 and 1969, he started to reach out to the Catholic community in an attempt to build bridges and engage them in the political process. He was sympathetic to the civil rights campaigners and wanted to introduce reform.

He soon found himself caught in an impossible situation. The Unionists were alarmed by his conciliatory approaches to the Catholics and feared he was going to give too many concessions. The Catholics, on the other hand, thought he wasn’t going nearly far enough.

O’Neill then alarmed Unionists more by going to meet the Irish Taoiseach Sean Lemass in an attempt to build better relationships with the Republic so they could work together for their mutual benefit in terms of trade, investment, tourism etc.

It was the first ever meeting between an Irish Taoiseach and a Northern Ireland Prime Minister. Unionists were appalled and suspicious. They were even more outraged the following year when Lemass visited O’Neill in Belfast. Many felt O’Neill was dangerously naïve and started plotting to remove him.

Rev Ian Paisley and the Divis Street Riots

Those fears of the Loyalist community soon found a voice in the Rev Ian Paisley. Paisley was a firebrand preacher with a hatred of Catholicism and a no surrender attitude to any form of change that would weaken Loyalist hold on power or the strength of the union with Britain.

He was alarmed by the conciliatory attitude of O’Neill. In 1964, he was furious to discover that the Irish tricolour was being flown in the West Belfast election office of a republican candidate for the forthcoming election to the British Parliament.

He decided to lead a march of Loyalists to remove it. Rather than run the risk of a confrontation with Paisley, the police removed the flag in an attempt to avoid any conflict. It was a disastrous miscalculation. The Catholic population were outraged, not just at the removal of the flag but because it had been done as they saw it, to appease a bunch of Loyalist thugs.

The incident led to two days of rioting in the Divis Street area of Belfast. Petrol bombs were thrown at police who responded with water cannon and baton charges as they tried to control the disturbances.

No one was killed and there was no gunfire but it was a shock to both sides of the community. The Catholics were alarmed at the ruthlessness of the police and their willingness to give in to Paisley. The Unionist community were alarmed at the rioting and feared what would happen next. It made them less willing to make concessions and the so the extremist views of people like Paisley gained momentum.

Protest marches and civil unrest

The growing civil rights movement also alarmed Unionists. In the early days, the movement contained many Protestants who accepted that change was necessary. They fell away, however, as attitudes hardened and violence increased.

Civil rights marches and protests had come under attack from Loyalists. In 1969, a march by a civil rights group called the People’s Democracy was attacked by Loyalist hardliners and member of the B Specials (a supplementary police reserve force) at a place called Burntollet Bridge in Co Derry. The brutality was captured by TV crews and was shown all across the world.

The pictures were an embarrassment to the British government. British Prime Minister Harold Wilson summoned O’Neill and demanded that he introduce reforms. He was willing to do so but faced opposition from the hardliners in his government.

Meanwhile, the campaign to oust O’Neill was gathering pace. He came under further pressure when water installations were bombed. The IRA was blamed and critics turned up the pressure on O’Neill saying that he had lost control of the situation and his weakness allowed the IRA to do as they pleased.

O’Neill resigned on 28 April, 1969 saying that the bombs had blown him out of office. It later emerged that the bombs had not been the work of the IRA, which at that point was still quite weak. The explosives had been set by the Loyalist paramilitary group the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) with express intent of undermining O’Neill.

The Battle of the Bogside and the arrival of British troops

O’Neill was succeeded by Major James Chichester Clark and shortly afterwards by Brian Faulkner but neither could stop the escalating violence and both were reluctant to concede any reforms.

The violence escalated to a new fatal level in Derry on 12 August, 1969 when Loyalists marching to celebrate the start of the Siege of Derry were confronted by angry Nationalists. RUC police officers tried to force the Nationalists back into the Catholic area known as the Bogside.

Nationalist youths erected barricades to stop the marchers. The RUC tried to disperse them with baton charges but then came under fire from petrol bombs. Tear gas was used for the first time in Ireland or Britain.

Riots then broke out in West Belfast as an act of solidarity with Derry. The police used machine gun fire. One bullet tore through the walls of a high rise flat in the Falls Road area and killed a nine-year-old boy.

The violence continued until 14 August when British troops arrived to restore order. At first they were treated as saviours by the Catholic population…but the relationship was soon to turn sour.

An inquiry by Mr Justice Scarman later reported that 10 people were killed in the riots, 154 were wounded by gunfire and 745 were injured in other ways. Of the 1800 families displaced, 1500 were Catholic.

The Revival of the IRA following the riots

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) had been slow to respond to the growing violence and unrest in the 1960s. The IRA had never accepted the partition of Ireland and had fought against it from the outset.

Between 1956 and 1962, the IRA had mounted what became known as the Border Campaign, which involved a number of shootings and bombings of installations along the border, but they had little effect. By the end of the decade, the IRA was largely a spent force.

Although the Loyalists feared them, they were fairly toothless and lacking in numbers. They were directed largely from Dublin by ageing leaders who had turned their attention to Marxist politics as much as Irish nationalism following the failure of Border Campaign.

The Battle of Bogside and similar confrontations in the late 1960s changed all that. Catholics did not trust the police to protect them and they soon lost faith in the British Army. They felt a need for a security and the IRA attempted to fulfil that role.

Every example of police or army brutality acted as a recruiting sergeant for the IRA and soon its membership began to swell. The new generation soon lost patience with the leaders of the old guard and looked for change. In 1969, they set up the Provisional IRA to represent the new generation who wanted direct action to oppose the police and the British troops. The name was only meant to be temporary but it stuck and was soon shortened to the Provos, the new and far more militant IRA.

The growing violence between 1969 and 1972

The period between 1969 and 1972 was the worst period of violence throughout the Troubles. This was due to the hardening of attitudes on both sides, the emergence of the newly energised IRA, and the growing strength of Loyalist paramilitary groups like the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and Ulster Defence Association (UDA).

There were also more incidents of killings by the police and troops… and perhaps most important of all, the mistaken belief by the Stormont government that the civil unrest was merely a law and order problem that could be solved by greater security measures.

1970 saw rioting all over Derry and Belfast, with atrocities committed on all sides. The year also saw a British General Election that returned a Conservative government in London. The Conservatives traditionally had close ties with Unionists and they allowed Northern Ireland Prime Minister Brian Faulkner to try to solve the problem by stepping up security.

The main plank of Faulkner’s policy was to introduce internment, which allowed the authorities to arrest and detain suspects without trial. It was introduced on 9 August, 1971 with Operation Demetrius. The Army rounded-up and interned 342 men. All except one were Catholic. No UVF or UDA men were interned until nearly two years later, even though they killed over 100 people between them.

The introduction of internment led to widespread rioting by Nationalists, leading to 13 people being shot. Rent and rate strikes followed and more people were killed as the protests continued. The British sent in more troops but the violence continued.

Then came perhaps the most infamous episode in the whole history of the Troubles, Bloody Sunday.

Bloody Sunday and the fall of the Stormont government

On 30 January 1972 a civil rights march in Derry was blocked by an army barricade. This led to a stand-off between protesters and troops. Some protesters started throwing stones and then to everyone’s astonishment, soldiers opened fire killing 13 people. A fourteenth victim died later in hospital.

An inquiry found that the victims had been unarmed.

The killings sparked outrage among the Nationalist community. More rioting broke out and the fury spread south to Dublin where protesters marched on the British Embassy and burnt it down. A new wave of recruits flocked to the IRA.

Television pictures of a Catholic priest waving a white handkerchief as he tried to attend to an injured victim were flashed across the world, causing shock and outrage, particularly in America.

It was a major embarrassment to the British government, which finally lost patience with Faulkner’s attempts to quell the violence using internment and heavy handed policing. The Stormont government was dissolved on 24 March 1972 and the British government imposed direct rule from London.

Direct rule and the Sunningdale Agreement

The violence, the bombings and killings continued unabated despite the abolition of Stormont, which pleased no one in Northern Ireland. The Unionists wanted their parliament back so they could govern themselves, and the Nationalists wanted the British out of Ireland without any conditions. Stormont rule or direct rule made very little difference to them.

The British Prime Minister Ted Heath and his Northern Ireland Secretary Willie Whitelaw then set about finding a solution to the problem. They briefly considered a united Ireland but dismissed it on the basis that the backlash from the Unionist population but be impossible to control. However, they felt that any solution would need to contain an “Irish dimension” meaning that the Irish government should be given a role in any new settlement.

After negotiations with the main parties in Northern Ireland, they came up with the Sunningdale agreement, named after the place in England where it was signed.

Sunningdale attempted to treat both sides of the community equally. It provided for a new Northern Ireland Assembly made up from all political persuasions, elected by proportional representation. There would also be a Council of Ireland involving representatives from the Republic.

Unionists were outraged. Not only did they have to share power but they also had to stomach some input from the Republic.

The IRA and its political wing Sinn Féin were also opposed to it because they felt it cemented British involvement in Northern Ireland. They wanted the British out altogether.

The issue split the Unionist party but nevertheless, elections were held and the new assembly did convene, made up of Faulkner and his mainstream Unionists on one side and Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP) members led by Gerry Fitt and John Hume on the other.

It was a new dawn but it was to be short-lived. In May, 1974 Loyalists staged a strike that brought Northern Ireland to a standstill. There was violence against anyone who dared defy the strike and some Catholics were murdered. Within weeks the power sharing experiment collapsed and Northern Ireland was back to direct rule.

Stalemate and stagnation in the aftermath of Sunningdale

Northern Ireland entered into a kind of military stalemate and political stagnation in the wake of Sunningdale. The British government set up a convention to discuss a political solution but it could find no way to make power sharing work so it fizzled out.

The IRA and the British government both came independently to the conclusion that they could not defeat each other militarily and so settled in for a long haul conflict.

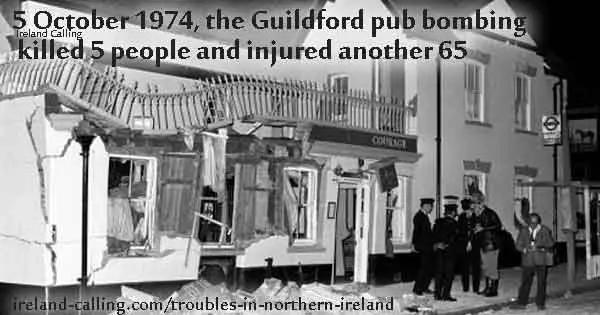

IRA ceasefires came and went, punctuated by what it called “spectacular” bombings that spread to English cities such Birmingham and Guildford. It also claimed high profile victims like Earl Mountbatten and Airey Neave.

Hope seem extinguished after the failure of power sharing and it was hard to imagine a solution that would work given the entrenched attitudes on both sides.

The Loyalist community still dominated. The British government tried to introduce more equality with employment legislation and laws against incitement to hatred but they had little effect.

In 1976, officials in Northern Ireland tried to appeal for peace with a publicity campaign featuring the slogan ‘Seven years is enough’.

Nationalists responded with the slogan, ‘700 years is too much’. The campaign suddenly looked like an own goal and was withdrawn.

Meanwhile the world was losing interest in Northern Ireland and it took a major bombing or murder to warrant any serious coverage in the media.

The dirty protest and political prisoner status

In 1972, an IRA man had gone on hunger strike in prison in an attempt to be classed as a political prisoner rather than as a criminal. Rather than risk the Nationalist backlash and adverse publicity of letting the man die, Northern Ireland Secretary Willie Whitelaw granted IRA prisoners Special Category Status. The new status gave them special privileges including being kept with other IRA prisoners in separate compounds.

A few years later, however, the British government embarked on a policy of “criminalisation” which meant that IRA inmates would be treated as common criminals because to treat them as prisoners of war was to give legitimacy to their actions.

The failed policy of internment was to end at Christmas 1975 and it was decided that Special Category Status would end in March 1976, to coincide with the opening of the new specially designed H M Prison Maze, set out in H block shapes that had been built next to the internment camp of Long Kesh.

The policy ran into problems on the very first day and brought more embarrassing publicity for the British government. The first IRA man taken to the Maze refused to wear the prison uniform and said it would have to be nailed to him to make him wear it. He clothed himself in a blanket instead and so began what became known as the blanket protest. Before long, this gave way to the dirty protest, in which prisoners smeared excrement on their cell walls.

The criminalisation policy was showing little benefit. By 1978, there were 250 prisoners on the dirty protest and they were attracting adverse publicity for Britain across the world.

In 1979, the IRA assassinated 10 prison officers in an attempt to make the British government relent but to no avail.

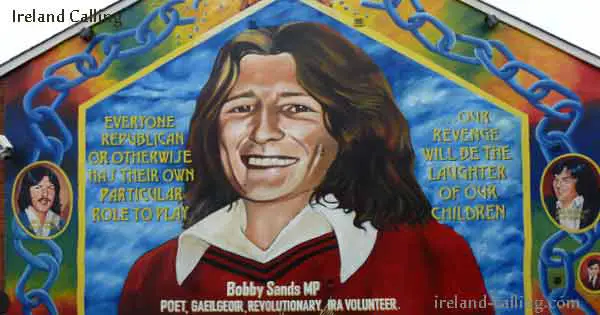

Bobby Sands, the hunger strikes and Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher was elected British Prime Minister in 1979. She was not a person given to compromise or appeasement, characteristics that were to later to earn her the name, the Iron Lady.

Her natural antipathy to the Republican cause was reinforced by three major bombings in 1979, the year that she came to power. One of her closest political allies, the MP Airey Neave, was killed by a bomb planted by the republican splinter group the Irish National Liberation Army. A few months later IRA bombs killed 18 British soldiers at Warrenpoint. At around the same time, the Queen’s cousin Earl Mountbatten was killed as he sailed off the coast of Co Sligo.

Thatcher’s response to these attacks was to add another 1,000 men to the RUC. She saw security and defeating the IRA as a more urgent priority than negotiations and reforms.

Meanwhile, the IRA was stepping up its campaign to achieve Special Category Status for its members in prison. In 1980, they began a series of hunger strikes with prisoners prepared to starve themselves to death unless their demands were met.

Bobby Sands began his hunger strike on 1 March 1981. As his health deteriorated, Republicans decided to put him up as a candidate for a by-election to the British parliament. He won a resounding victory, sending shockwaves through the Loyalist community and the political establishment both in Britain and Ireland.

Sands’ victory was a major embarrassment for Thatcher. How could she dismiss him as a terrorist when he had just won the backing of the voters and been and elected as a member of the British parliament? She dodged the issue and still refused to budge, even after Sands died on 5 May.

Ten more hunger strikers were to die before the IRA called off the campaign. They won some concessions but didn’t achieve the Special Category Status. To many across the world, however, they had won a moral victory. But there was more to it than that. The treatment of the hunger strikers inspired yet more recruits to join the IRA. Perhaps more importantly, Sinn Féin, realised that Republicans could win elections. It transformed their thinking as they started to consider the power of the ballot box.

Speaking at a Sinn Féin conference in 1981, publicity officer Danny Morrison addressed the meeting with the famous phrase: “Will anyone here object if, with a ballot box in one hand and an armalite in the other, we take power in Ireland?”

They started to win elections and would eventually overtake the SDLP as the voice of Catholic Nationalists. In 1983, Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams defeated the SDLP’s Gerry Fitt as MP for west Belfast. It represented a generational shift that signalled Sinn Féin’s arrival as a major electoral force.

The Anglo Irish Agreement

While the hunger strikes and various bombings and riots were grabbing the headlines in the early 1980s, work was going on behind the scenes without the knowledge of either the IRA or the Unionists.

Thatcher was broadly pro-unionist when she came to power in 1979 and at first Loyalists welcomed her as an ally. Her refusal to give into the IRA and the hunger strikers added further reassurance that she was on their wavelength. However, within a few years they were accusing her of betraying them and the Rev Ian Paisley even implored God to bring vengeance down upon her.

The Irish government had been dismayed by the failure of the Sunningdale power sharing agreement and the ensuing stalemate between Nationalists and Unionists. Irish Taoiseachs began to approach the British government to see if it would be prepared to discuss issues of mutual concern in the North.

For all her hard line public stance, Thatcher was prepared to listen and held discussions with both Charles Haughey and then Garret Fitzgerald. Unionists were furious when they discovered talks about Northern Ireland had taken place without their knowledge.

Meanwhile, the IRA was redoubling its military campaign following the treatment of the hunger strikes. They planted more bombs in England, killing army band members and shoppers at the world famous Harrods. Loyalists were carrying out killings of their own and in March 1984, Gerry Adams was shot in a UDA attack. He was injured but survived.

Thatcher escapes IRA bomb at Grand Hotel in Brighton

Then in October, 1984, the IRA planted a bomb in the Grand Hotel in Brighton where Thatcher’s Conservative Party were staging their annual conference. Several people were killed and many more injured. Thatcher herself only narrowly escaped with her life.

The Brighton bombing might have been on her mind a month later when she met Irish Taoiseach Garret Fitzgerald to discuss proposals for co-operation in the North. She famously dismissed them all with the words “Out, out, out…”

Fitzgerald was dismayed but to everyone’s subsequent surprise, negotiations went on behind the scenes.

Then on 15 November, 1985 Thatcher and Fitzgerald signed the Anglo-Irish Agreement. She did so because she believed it would help to secure Northern Ireland as part of the United Kingdom after Fitzgerald agreed to a clause that there could be no change in the North’s constitution without the consent of the majority of the people.

On the other hand, it also gave the Republic a consultative role in the affairs of the North, and that was too much for Unionists to stomach. The protests were taking place before the ink on the agreement had dried.

Unionist reaction to the Anglo-Irish Agreement

To the Nationalists, and the Irish and British governments, the Anglo-Irish Agreement was a significant but inoffensive development. It set up an Anglo-Irish Intergovernmental Council with offices in Belfast. One of its functions would be to enable Catholics to voice grievances to Irish officials, which would then be passed on to British officials to consider.

The Irish government could also put forward proposals on certain matters but it was up to the British to decide whether or not to act on them. Most of the time they didn’t.

One of the main aims was to entice Unionists to edge back towards power sharing. The agreement meant that if a power was devolved to Northern Ireland, the Irish government would lose all input on that subject. The more powers that were devolved, the less influence for Dublin. On the other hand, if the Unionists wouldn’t agree to share power then Dublin’s influence would continue.

The Unionists rejected it completely, seeing it as some sort of trap to lure them towards more power for the south. They were also outraged that it had been introduced over their heads and without their knowledge.

They set about strangling it at birth. Unionist MPs resigned to force by-elections to give the electorate a chance to voice their disapproval at the ballot box. Marches and rallies were called together with strikes.

The British government stood firm and the RUC stepped in to prevent intimidation by Loyalist paramilitaries during marches and strikes. The Northern Ireland Secretary Tom King and the RUC accused some Unionist MPs of rubbing shoulders with Loyalist terrorists.

Loyalist fury increased and the UDA and UVF started petrol bombing the homes of hundreds of police officers and also launched attacks on the homes of Catholics.

These were all measures that had enabled Loyalists to destroy political initiatives in the past but not this time. Thatcher visited Belfast to reiterate her commitment to the Anglo-Irish Agreement.

The Loyalist backlash did, however, have some success. It made the British shelve some of the AIA provisions such as ensuring that army patrols were always escorted by the police. The British did press ahead with employment legislation to reduce discrimination against Catholics and this had some success, although Protestants were still more likely to have jobs.

Britain’s refusal to give in to the Unionists and scrap the AIA led to an extraordinary outburst from Ian Paisley during one of his sermons when he called on God to wreak vengeance on Thatcher. He said: “We pray this night that thou wouldst deal with the Prime Minister of our country. O God, in wrath take vengeance upon this wicked, treacherous, lying woman. Take vengeance upon her O Lord, and grant that we may see a demonstration of thy power.”

Despite Paisley’s plea, God left Thatcher alone.

Bombs and the Ballot box – Sinn Féin and the IRA

While the Unionists threw their energy into campaigning against the Anglo-Irish Agreement, Sinn Féin was turning its attention to elections, both in the North and the Republic. In the past, they had stood in elections in the Republic on the basis that they would not take up their seat because they did not recognise the legitimacy of the Dáil.

By the mid-1980s, their attitude was changing, with younger members like Gerry Adams arguing that it made no sense to boycott an assembly that the Irish people recognised and accepted. It was a change of heart that was to see Sinn Féin develop into a political force that neither the British nor the Irish government could ignore.

At the same time, the IRA was concentrating on its military campaign, It got arms from Libya and used them to pull off devastating bomb attacks in both England and Ireland. It liked to stage what it called ‘spectaculars’ because they got maximum publicity.

However, the rising number of deaths and injuries involving innocent people made it impossible for the British government to speak with Sinn Féin or enter into negotiations with them – at least not in public.

Matters came to a head on 8 November 1987 when an IRA bomb exploded at a poppy day memorial ceremony in Enniskillen to commemorate those who fought in the two world wars. Eleven people were killed and many more injured.

Thatcher was furious and banned British radio and TV stations from broadcasting statements from Sinn Féin spokesmen. Their voices had to be dubbed by actors instead. It seemed a pointless gesture to many but the main effect was that it isolated Sinn Féin from the political process.

The British military also stepped up its fight against the IRA. Eight IRA members were shot dead by troops as they prepared a bomb attack in Armagh. Three more were shot dead in Gibraltar. The deaths were controversial and Britain was accused of operating a shoot to kill policy that overlooked the niceties of fair trials.

Nevertheless, the British persisted and any prospects of peace seemed as far away as ever.

Britain declares it has no selfish or strategic interest in Northern Ireland

Throughout the 1980s, the British and Irish governments maintained contact and continued to look for ways forward.

Then the new Northern Ireland Secretary Peter Brooke made two landmark speeches that helped to change people’s thinking. In 1989, he declared that the IRA could not be defeated by military means. In 1990 he declared that Britain “had no selfish, strategic or economic interest in Northern Ireland”.

Unionists were unhappy about both declarations but Brooke continued to reach out to them. In 1991, they agreed to enter into exploratory talks after Brooke agreed to the suspend meetings of the Anglo-Irish Intergovernmental Council.

Sinn Féin were excluded because of the continuing bombings by the IRA. By this time, they had replaced the SDLP as the major Nationalist political party in the North so it was hard to see how any talks could get very far without them.

In the end, it didn’t matter as the talks didn’t get very far anyway and soon broke down. That did not mean they were a total failure. At least the Unionists had agreed to take part. More importantly, they had agreed to take part even though the British wanted to adopt a “three strand” approach covering Unionists and Nationalists in the North, the relationship between the North and South, and the involvement of both the Irish and British governments.

It meant that however tentatively and however reluctantly, Unionists were at least prepared to consider some settlement that involved the Republic.

Peace was still a long way off but that was a significant step towards what would soon become known as the Peace Process.

Ireland Calling will soon publish an article on the Peace Process that led to power sharing between Unionists and Nationalists in the new Northern Ireland Assembly.

troubles.html