Tom Crean was one of the bravest and toughest explorers of the early part of the 20th century. He took part in three polar expeditions and overcame horrific conditions and energy sapping journeys to not only survive himself but to save the lives of his colleagues.

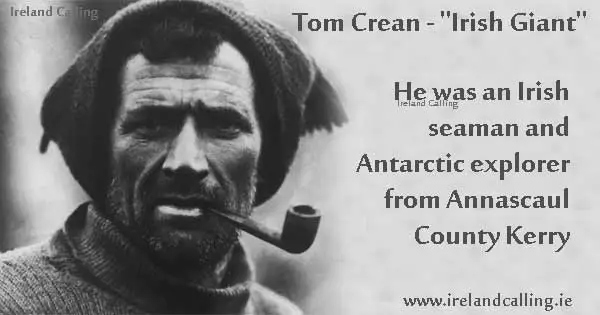

He was known as the ‘Irish Giant’, both for his physical stature and strength and also for his unwavering spirit and leadership in even the most hopeless of circumstances. His achievements and bravery were immense.

The qualities that set Crean apart were his positivity and faith, and the ability to inspire those around him to keep going.

Crean was born in Annascaul in County Kerry in 1877, one of ten children. His father was a farmer and Crean would often help out with daily tasks as a child.

Commander Scott

At the age of 15, Crean travelled to England and joined the British Navy. He was a hard worker and popular amongst his comrades and superiors.

In 1901, he found himself stationed in New Zealand and met Commander Robert Scott, captain of the expedition ship the Discovery. Scott was stopping off in New Zealand to gather supplies for an expedition into the unknown regions of the Antarctic.

Crean volunteered to be a member of the Discovery’s crew and was accepted by Scott.

The trip was a success, both for Scott and for Crean. Although he had joined the crew as a mere deck hand, Crean had caught the attention of Scott for his leadership qualities, his strong work ethic and his positive attitude.

Crean was promoted to Petty Officer 1st Class and served under Scott for the next few years. By the time of Scott’s next expedition, Crean had become a key member of his crew.

800 mile trek across the Antarctic

In 1910, Crean was on board Scott’s Terra Nova as it sailed into freezing, ice-filled waters of the Antarctic on a mission to reach the South Pole.

It was on this expedition that Crean’s fearless nature and desire to succeed really surfaced.

The crew had marched with Scott across the ice and snow of the Antarctic towards the South Pole for weeks and had travelled roughly 800 miles inland.

Scott estimated that they were roughly 150 miles from the South Pole itself. He ordered Crean and two others to return to the base camp. He wanted to keep the crew in separate groups in case any one group got into difficulty, they could be rescued.

Crean and his two colleagues, Teddy Evans and William Lashly, had the frightening task of trekking 800 miles back to the base camp on their own without the safety of the group to support them.

They set off on their journey and navigated through wind storms, ice fields, and the deadly snow bridges across the ice blocks.

These were described as the “crossbars to the Hs of Hell” as the snow could give way underfoot at any point, plummeting anyone stepping on it into narrow chasms underneath the ice.

Anyone who fell down one of these chasms would have no chance of survival. If the fall didn’t kill them instantly, then they would have sustained such injuries to make any chance of climbing back up to safety impossible.

There would also be no hope of rescue with the chasms so narrow, deep and slippery, and the snow at ground level so unstable.

Crean, Evans and Lashly crept their way through these deadly crevasses, knowing that every step they took could be their last.

Eventually, they made their way on to more stable ground and were about 100 miles from the safety of their base camp.

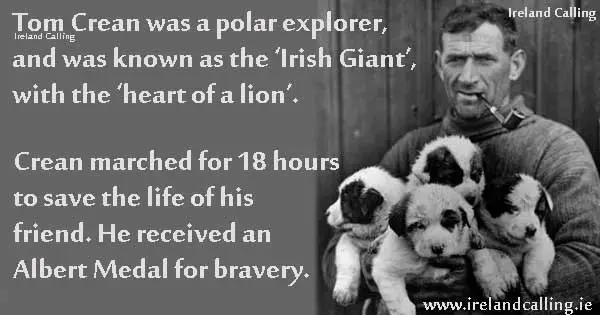

‘The heart of a lion’

By this point, Evans had gone down with scurvy and was too weak to walk unassisted. The other two helped him along before deciding their best use of energy was to tow him along on a sledge.

The trio moved forward like this for another 65 miles before Evans had become so weak he didn’t even have the strength to be towed any further.

It was decided that Lashly would set up a temporary camp for himself and Evans and try and nurse him back to health. Crean would complete the last leg of the journey on his own.

He marched through the wind and snow for 35 miles without stopping, knowing that every moment was crucial in getting help for Evans.

Crean did make it to the base camp and returned with a rescue team for his two colleagues.

Crean had marched non-stop for 18 hours to save the life of his friend. Evans swore he would never forget the courage shown by both Crean and Lashly in saving his life.

He described the two men as having “hearts of lions”. Both received an Albert Medal for their bravery.

Joining Sir Ernest Shackleton on the Endurance

Crean took part in his third and final polar expedition in 1913.

Again his willingness to help others and his steely drive for survival were displayed. Crean was selected by Sir Ernest Shackleton to be part of the crew on board the Endurance and part of a six-man team that would help him sledge across the Antarctic.

The expedition ran into difficulties almost immediately. The ship got trapped by ice in the Weddell Sea. Unable to continue forward, or go back, the crew had no choice but to abandon ship and take refuge on one of the surrounding ice floes.

It was agreed that they would wait there until the ice thawed enough for them to try and return home in the Endurance’s lifeboats.

After living on the ice floe for more than six months, Shackleton ordered that the crew must launch the lifeboats and attempt to navigate their way through 100 miles of the icebergs to Elephant Island. There, they could assess their position.

Crean stepped in to lead one of the lifeboats during the voyage after the commanding officer suffered a breakdown and the crew did manage to make it to Elephant Island alive.

However, the island was a desolate rock with little resources for food and shelter. The crew would not survive there for long. There was also no chance of a rescue boat finding them there. The island was merely a stepping stone for a successful escape.

17 days at sea in tiny lifeboat

Crean was one of six men chosen by Shackleton to sail north to Georgia Island, where there was a whaling station and proper supplies. The alarm could be raised from there and a rescue mission sent back to save the remaining crew at Elephant Island.

Crean and the others endured 17 days in the Southern Atlantic Ocean, with freezing wind and rain and treacherous sea. They were all severely dehydrated, undernourished and exhausted by the time they landed at Georgia Island.

Unfortunately, their suffering was not complete. The boat had landed on the south side of the island, whereas the whaling station and their saviour was on the north side.

Shackleton ordered that a voyage around to the north was too dangerous, given the torrential conditions they had already endured.

He also feared a miscalculation could lead to the boat being carried into the Atlantic Ocean, missing the north side completely.

Crean was selected along with one other to accompany Shackleton by foot across the mountains of Georgia Island to the whaling station. The other three men would set up camp on the shore and wait for rescue.

Return to Elephant Island for those left behind

“He always sang when he was steering, and nobody ever discovered what the song was … but somehow it was cheerful.” Sir Ernest Shackleton on Tom Crean.

Shackleton, Crean and the other man, Worsley, set off with no tents or sleeping bags and little food and water. They were intent on completing the journey in one go.

They had hammered nails through the soles of their boots to serve as crampons on the slippery and icy mountains.

The trio marched, climbed, slipped and clambered the 30 mile journey to the nearest whaling station.

It took them 36 hours, which they completed without rest. It was the first journey by foot across Georgia Island, without tents, maps or sleeping bags.

The alarm was raised and a rescue team was sent to save the men on the south side of the island.

Shackleton, Crean and Worsley all took part in rescue missions to save those left at Elephant Island. The floating ice made it almost impossible to get back and there were four failed attempts before the men were finally rescued.

Crean returned to Britain and continued to serve the Royal Navy until 1920. He received three Polar Medals for his achievements throughout his career.

Crean then returned to Ireland and lived out the rest of his life quietly in his native Kerry with his wife and children.

The family ran a pub called ‘The South Pole Inn’.

Irish explorer reveals what it’s like to follow footsteps of Ernest Shackleton