The Battle of the Bogside was one of the first major confrontations of the Troubles and changed Northern Ireland forever. In the ensuing riots in Derry and Belfast, 10 people were shot dead, 154 were wounded by gunfire and hundreds more had their homes burnt out, most of them Catholics.

Television pictures of the violence were beamed across the world, demonstrating the deep scars between the Catholic and Protestant communities and the volatility in their relationship.

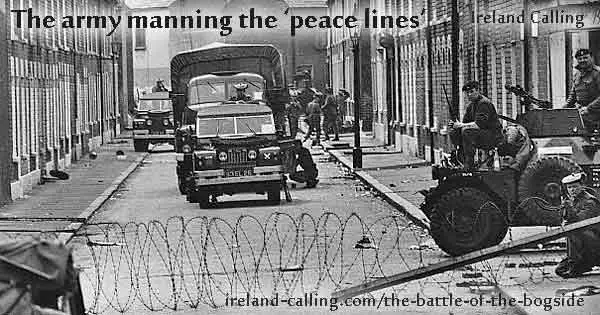

In an attempt to stem the violence, the British government sent in troops to restore order. It was codenamed Operation Banner and was supposed to be a temporary measure. In fact, it turned into a 38-year marathon… Britain’s longest ever military campaign.

The Battle of the Bogside was sparked off by a march by the Apprentice Boys of Derry. The Protestant Loyalist community staged several marches during the summer to commemorate historical events, most of which relate to military campaigns of William of Orange, who became King of England after defeating the Catholic James II.

In 1688, James laid siege to the city of Derry and brought the inhabitants to the verge of starvation. The siege was broken by William and the citizens of Derry were saved.

Every year, an association known as the Apprentice Boys of Derry stages a march to commemorate the start of the siege, which began after young apprentices closed the gates of the city against James.

The marches are seen as intimidating and unnecessary by the Catholic community and they are still controversial today, despite the Peace Process.

On 12 August 1969, the Apprentice Boys’ march was confronted in Derry by Nationalists youths, outraged that the marchers felt they had the right to parade through their community. Stones were thrown by both sides and the situation soon escalated and got out of control.

Police officers from the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) tried to clear a path through for the marchers but were answered by more stone throwing from the lines of Nationalist youths. The officers staged a baton charge and the youths responded with petrol bombs.

The police then used tear gas in an attempt to disperse the crowds. It was the first time that tear gas had been used in Ireland or Britain. The Nationalist youths erected barricades, which the police could not breach. The fighting continued throughout the night and for the next two days.

Troops arrive in Northern Ireland for the first time during the Troubles

On August 13, rioting broke out in west Belfast with Nationalist youths showing their solidarity with the demonstrators in Derry. After their failure to break through barricades in Derry, the police used armoured cars with machine guns to try to disperse the crowds. The guns were fired in bursts along the Catholic Falls Road area and a bullet ripped through the wall of a block of flats and killed a nine-year-old boy who was asleep at the time.

Police then staged baton charges through the protesters and were followed by Protestant youths who attacked and burned the homes of Catholics. Houses were ablaze and thousands of people fought in the streets of west Belfast.

It was clear that the RUC could not cope. The Northern Ireland Prime Minister James Chichester-Clark asked British Home Secretary Jim Callaghan to send in the army to quell the violence and keep the warring factions apart. Callaghan agreed immediately and within hours, troops who had been on standby aboard HMS Sea Eagle were entering Derry.

The army arrived on 14 August and was warmly welcomed by the Catholic community who saw them as protectors against violence from the RUC and the police supplementary force, the B Specials. The relationship between troops and the Catholic community would soon turn sour but at that moment at least, the troops were seen as saviours.

The government later commissioned an official inquiry into the rioting by one of the country’s leading judges, Mr Justice Scarman. His report stated that 10 people had been shot, 154 wounded by gunfire and 745 were injured in other ways. More than 1,800 families had been driven from their homes, 1,500 of them were Catholics.

The Battle of the Bogside and the accompanying riots in west Belfast changed Northern Ireland completely. The British and the wider world were shocked that the animosity between the two communities could erupt into such violence.

The erection of ‘peace lines’ made residential streets look like war zones

The political differences between the two sides became etched into the landscape as the army began to erect what it called peace lines. These were basically barricades to keep the warring factions apart. They started out as simple lines of barbed wire but later developed into huge constructions of concrete and metal, making residential areas look like war zones.

The role of the RUC was undermined by its failure to control the rioting and its failure to win the trust of the Catholics. The B Specials were also discredited and the British government ordered that they should be disbanded. The army was to become the main security force for the next 30 years, although the RUC continued to play an important if controversial role.

The attacks on Catholics also had the effect of bringing the Republic into the equation. Like everyone else, the Taoiseach Jack Lynch was horrified by the scenes of violence. Until that point, Dublin politicians had been ambivalent about getting involved in the affairs of the North. Not anymore.

Lynch’s ministers debated whether they should get involved, perhaps by sending arms to the Catholics or even by sending troops. Such measures would have been extraordinary steps to take and in the end Lynch did neither, but he did take some action that reassured the Catholics and outraged the Unionists. First, he broadcast a speech which included these words: “It is clear that the Irish government can no longer stand by and see innocent people injured and perhaps worse.”

This led Unionists to fear an invasion from the south, and even Callaghan wondered if that might happen. Lynch didn’t do anything so drastic but he did set up field hospitals near the border to treat the Catholic wounded. He then allocated £100,000 for the relief of distress and also arranged for the Irish army to provide men from Derry with arms training.

Through these actions, Lynch involved the Republic in the affairs of Northern Ireland – an involvement that was recognised by successive British governments who would soon acknowledge that there would have to be an “Irish dimension” to any political solution for Northern Ireland.

Attacks on Catholics led to the resurgence of the IRA

The other major effect of the rioting in Derry and Belfast was that it led to the resurgence of the IRA.

The IRA had opposed the setting up of the six-county state of Northern Ireland since the days of the Irish War of Independence. It had fought sporadic campaigns against it, including the Border Campaign of the late 1950s and early 60s when it set off a series of explosions at installations and facilities along the border with the Republic. It had also targeted police officers but the campaign had not had much effect and by the mid-60s the IRA was looking feeble and dispirited.

The Battle of the Bogside changed all that.

Most Catholics in Northern Ireland didn’t support the IRA or approve of its tactics but would turn to it for protection in times of high tension. Yet, during the Battle of the Bogside and the riots in Belfast, the IRA had been conspicuous only by its absence.

IRA commanders faced scathing criticism and scorn from the Catholic community for failing to protect them against attacks from Loyalists and the RUC. Graffiti with the words “IRA – I Ran Away” appeared on walls. The words could equally have been written by angry Catholics who felt let down or scornful Protestants who felt triumphant but either way it was a humiliating experience for the organisation.

It began to re-examine its role and soon its numbers were swelled by hundreds of new recruits who had been radicalised by their experiences in the rioting.

These were younger and more militant than most existing IRA members who were led by officers in Dublin. Soon they would engineer a split in the organisation to create the Provisional IRA, which would begin as a splinter group but then effectively take over the organisation completely.

When Taoiseach Lynch spoke out about the Troubles in Northern Ireland