Seán Lemass was a teenage rebel who fought in the Easter Rising and went on to become Irish Táoiseach more than 40 years later. He is often referred to as the father of modern Ireland because of the economic reforms he introduced to promote industrial growth and encourage foreign investment.

Policies he began in the 1960s culminated in several companies from the United States and elsewhere making a substantial investment in Ireland, eventually leading to the Celtic Tiger years in the 1990s when Ireland’s economy was one of the fastest growing in the world. He is regarded by many people as Ireland’s greatest ever taoiseach and even his rivals have acknowledged his huge achievements.

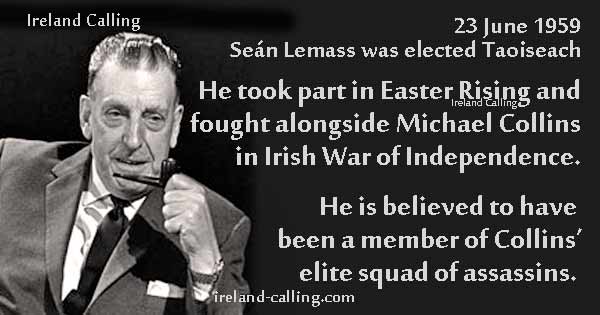

Seán Lemass was born John Francis Lemass on 15 July, 1899 at Ballybrack in Co Dublin. He developed strong nationalist views at an early age and preferred to be called by the Irish version of his name, Seán. He fought and was captured in the Easter Rising in 1916, but was spared execution by the British because of his young age, 16.

Lemass fought for Ireland again in the Irish War of Independence and was allegedly one of the ‘Twelve Apostles’ who killed 14 British soldiers on the order of Michael Collins. He was arrested and put in prison but was released when the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed in 1921.

After the treaty was signed, Lemass sided with the anti-treaty faction of the IRA, and fought under Rory O’Connor in the Irish Civil War.

He was one of the anti-treaty soldiers that seized the Four Courts in Dublin, but managed to escape when the buildings were surrendered.

He was one of the anti-treaty soldiers that seized the Four Courts in Dublin, but managed to escape when the buildings were surrendered.

Again, Lemass was captured and put in prison. He was released on compassionate grounds when his brother’s remains were found in Dublin mountains after he had been executed during the war.

Lemass got married on 24 August 1924 to Kathleen Hughes despite oppostion from her parents who objected to his rebel background. The couple had four children, including Maureen who married Charles Haughey, who later went on to become Táoiseach.

In 1926, Lemass helped to persuade Éamon de Valera not to give up on politics, as he was frustrated with his party Sinn Féin and their apparent acceptance of the Irish Free State. De Valera had always wanted Ireland to become an independent republic, and was considering leaving politics if his own party no longer shared his vision.

However, Lemass talked him into setting up a new party that could pursue that goal. Fianna Fáil was formed in 1926, with Lemass one of the founding members.

However, Lemass talked him into setting up a new party that could pursue that goal. Fianna Fáil was formed in 1926, with Lemass one of the founding members.

In 1932, de Valera was elected leader of the Irish Free State. He appointed Lemass to his cabinet as Minister for Industry and Commerce, and the two men were now governing the Irish Free State that they had fought to destroy only a decade earlier. It was a difficult time with the world in recession following the Wall Street Crash and the Great Depression.

De Valera and Lemass oversaw a trade war with Britain after it imposed tariffs against Irish goods between 1933 and 1938. Ireland’s economy was badly damaged and didn’t recover until decades later. Lemass established the Industrial Credit Corporation to provide investment and stimulate the economy but progress was slow and thousands of people had little choice to emigrate to find work.

There were some successes, however, most notably the establishment of the national airline, Aer Lingus, which Lemass later described as his greatest acheivement. Nevertheless, many economists consider that Lemass, under De Valera’s influence, adopted a too protectionist approach to trade with the imposition of tariffs and the country suffered as a result.

After the Second World War Lemass managed to acquire $100m investment from the United States under the Marshall Aid plan. The money was used to modernise Ireland’s road network and although it helped, the economy remained stagnant and emigration continued throughout the 1950s, particularly to the United Kingdom, which was rebuilding rapidly following the war years.

Lemass remained by de Valera’s side until he succeeded him as leader of Fianna Fáil and became Taoiseach himself in 1959. Perhaps because he was free of De Valera’s influence, or perhaps because he had seen that his measures had not worked in the past, he seemed to do an about turn on economic policy. He was impressed by the work of a rising civil servant called Ken Whitaker, who was Secretary of the Department of Finance.

Whitaker was an advocate of free trade and produced a paper called, First Programme for Economic Expansion, in 1958. It became known as the Grey Book and was eagerly taken up by Lemass who was attracted by its radical ideas and ambition. Lemass began to implement the policies by ending protectionism and encouraging free trade, encouraging a move from agriculture to industry and services. He also began the highly succesful policy of providing grants and tax breaks to foreign companies prepared to invest in Ireland.

In 1960, Ireland signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which was designed to reduce tariffs. In 1965 it signed the Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement, which again helped boost trade and prosperity.

Lemass served for seven years, and oversaw a period of rapid economic growth in the country. He believed that industrialisation was the best thing for the future of Ireland.

The Irish economy flourished under Lemass’ leadership with steps taken to encourage investment in production in Ireland from both at home and abroad.

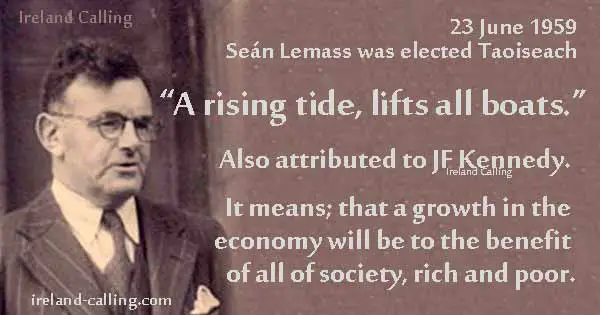

One of Lemass’ famous quotes from this time was: “A rising tide, lifts all boats.” This has also been attributed to President Kennedy, but it illustrates his belief that growth in the economy benefits of all of society, rich and poor.

Lemass resigned as Táoiseach on 10 November 1966. He died on 11 May 1971 at theMater Hospital in Dublin. He was given a state funeral and buried at Deansgrange Cemetery.

Seán Lemass is regarded by many as the Ireland’s best ever táoiseach. Even his rivals in Fine Gael like Garret Fitzgerald and John Bruton have praised his vision and his leadership qualities. Using Whitaker’s ideas he helped to create modern Ireland by reducing trade barriers and encouraging foreign investment on a spectacular scale. Part of his greatness lay in his willingness to reject his own protectionist policies that had failed in the past, and being prepared to accept new and bolder ideas from a younger generation.

He began the process of Ireland trying to join the European Economic Community (forerunner to the EU). He failed but the groundwork he laid came to fruition two years after he died when Ireland was finally admitted to the EEC in 1973.

* * *