Robert Burke was the leader of the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition across Australia in the early 1860s.

Burke was born in Galway and served in the British and then Austrian army before returning to Ireland and joining the police force. He later moved to Australia and became part of the newly formed Victoria police force.

Burke – leader of expedition

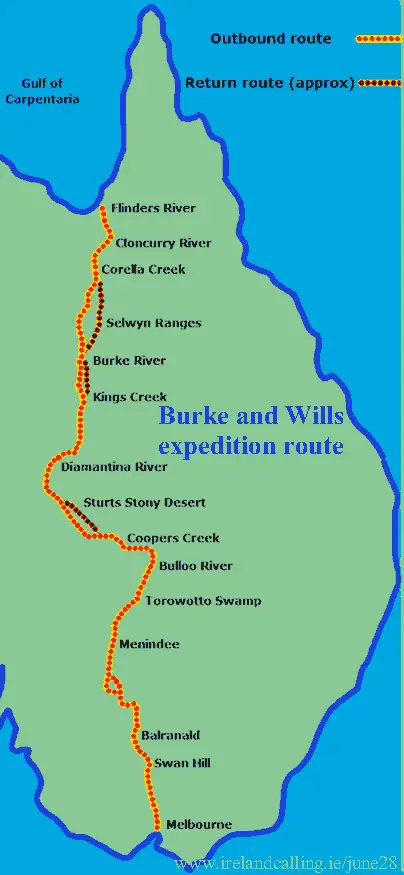

In 1860, Burke was made leader of a group of explorers aiming to travel across the whole of Australia south to north, from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria.

He appointed William Wills as his right-hand man and second-in-command for the mission.

A completed trip with details of the unknown landscape was worth a £2,000 reward from the Australian government.

Burke set off from Melbourne with his team of 19 men, 23 horses and 26 camels on 20 August 1860.

Within a month of battling through the difficult conditions and searing heat many of the men had given up, including the team medic.

Group split to allow weaker men to rest

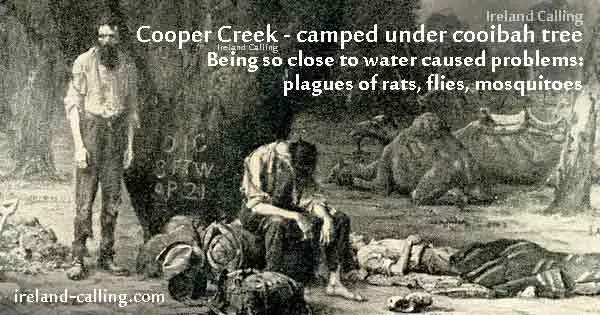

In October, the group split in two with the weaker men staying at Menindee to rest while the others continued on to Coopers Creek (sometimes know as Cooper Creek or Cooper’s Creek) where they would wait for the others to catch up.

Shortly before the advancing group reached Coopers Creek, Burke sent William Wright back to Menindee. Wright was told to gather more supplies and deliver them and the resting group to Coopers Creek using his newly acquired knowledge of the terrain.

Burke splits the group again

Burke’s group reached Coopers Creek in November and he made the decision that he would split the group again. He would lead a small team of William Wills, Charley Gray and John King onwards, while William Brahe would take control of the rest. Brahe was told to set up camp and wait to allow Wright’s Menindee group to catch up.

Obsessed with reaching Gulf of Carpentaria first

Burke was concerned that another expedition led by explorer Captain Charles Sturt would reach the Gulf of Carpentaria first and beat him to the £2,000 reward.

Burke and his advancing group set off towards the Gulf of Carpentaria in mid-December with the understanding that they would return to Cooper Creek in April once they had successfully completed the journey. If they hadn’t returned by the agreed date, then Brahe must assume they have got into difficulty and set out on a rescue mission.

Burke and his team reached Flinders River, on the Gulf of Carpentaria in February but harsh weather conditions meant they couldn’t advance further. The wet season rains had flooded the swamps and the decision was made to turn back towards Coopers Creek.

Burke missed Brahe by just nine hours

The return journey was unforgiving with the men now suffering from malnutrition and starvation.

One member of the group, Charley Gray, died and the others spent a day resting and burying his body.

They finally reached Coopers Creek on 21 April, but found it deserted.

Brahe’s group had not been met by the Wright’s, and had given up waiting for Burke to return. Short on supplies themselves, Brahe’s group travelled back towards Menindee to find Wright and raise the alarm of Burke’s missing group.

Brahe left some food and supplies buried at the camp in the case of either Burke or Wright arriving.

He carved a note into the tree above the buried supplies explaining his actions. Brahe and his men had left the camp just nine hours before Burke returned.

Burke continues on to Mount Hopeless

Burke arrived at Coopers Creek and found the note and supplies left by Brahe. They ate and rested but they still had a decision to make. Should they wait at Coopers Creek and hope to be rescued? Or continue on and hope they make it back to civilisation?

It was decided that they continue on, to the nearest known settlement, a cattle ranch near Mount Hopeless. Mount Hopeless was named by another explorer, Edward Eyre who had his own failed expedition trying to reach the centre of Australia. He climbed onto a rocky mound to try and see a possible exit after becoming trapped in a salt lake in the desert. He was eventually rescued by French fishermen after finding his way to the coastline.

Burke and his group were not so fortunate though. They were now down to three men, and set off to Mount Hopeless.

Cruel twist at Coopers Creek

A cruel twist occurred when Brahe and Wright met in between Coopers Creek and Menindee. They decided that they should use the supplies Wright had, and go back to Coopers Creek to see if Burke was there.

When they got to Coopers Creek, Burke’s group had already left for Mount Hopeless, and the mark on the tree had not been changed. As it all looked the same as when Brahe left it, they assumed that Burke had not been there, and so they left. They didn’t think to dig and check if the buried supplies were still there.

Burke’s group exhausted

Burke’s men were too exhausted to make it to Mount Hopeless Their horses and camels had all by now perished so the men couldn’t carry enough water to leave Coopers Creek. They traded sugar with native Aborigines for food and began journeying down the river in the hope of rescue.

Wills became too weak to continue and insisted the other two go on without him. They left him food and water and carried on. Two days later Burke also collapsed with exhaustion and died.

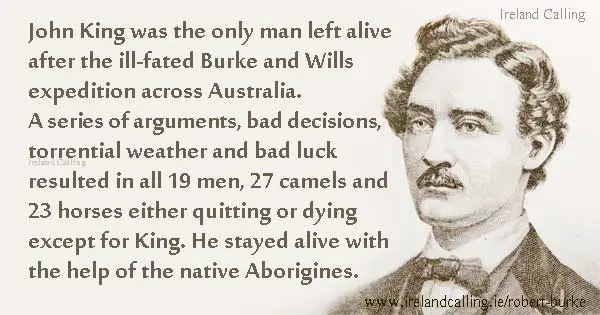

John King – sole survivor

The one remaining man left alive was John King of County Tyrone. He stayed with Burke for a day after he died, before returning to see if Wills had survived. King found Wills had also died.

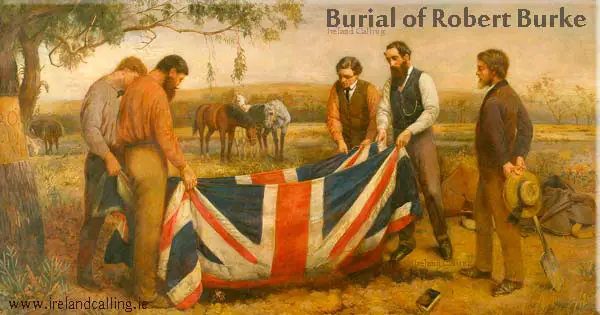

King managed to survive with the help of the Aborigines before eventually being rescued by Alfred William Howitt. Howitt ordered his men to escort King back to Melbourne and buried the bodies of both Burke and Wills.

The exact date of Burke and Wills deaths are unknown, but both men are widely believed to have died on 28 June 1861.

King was hailed as a hero and given a state pension of £180-a-year. He returned to Melbourne on 29 November 1861, more than 15 months after setting off as part of a 19-strong expedition of men.

Images copyright Ireland Calling

history.html