There were an estimated 250,000 Irishmen who fought as part of the British Army during the First World War.

However, by the time it ended in 1918, Ireland had already witnessed the Easter Rising. The IRA were then about to embark on a guerrilla war against the British in the War of Independence.

This meant that many of the Irish World War One soldiers were never honoured and celebrated to the full. One of these soldiers was named Patrick Armstrong. Historians from the University of Limerick have created an online exhibition so that his story can be heard.

‘Dr Pat McMahon has written this introduction to the Pat Armstrong story. Dr McMahon is a historian attached to the department of history, University of Limerick. He, along with Anna-Maria Hajba, Ken Bergin and Jean Turner form the research and compilation team who have created the online exhibition of the Armstrong archive, ‘It’s a long way to Tipperary’.

An Irish story of the Great War

It’s a long way to Gallipoli: From Tipperary to the Turkish peninsula

“The Turkish dead were so thick that I had to walk on them.”

On 25 April 1915, when Allied forces landed on the Turkish peninsula of Gallipoli few would have predicted the devastation that lay ahead. After eight months of terrible fighting to secure the sea route between Britain and France in the west and Russia in the east, it was obvious they had failed. The Allied campaign was an unmitigated disaster with huge numbers of casualties inflicted upon the belligerents, with figures varying from source to source.

For Captain William Maurice ‘Pat’ Armstrong, the journey to Gallipoli began in Tipperary when he left his family home to be educated in England, and follow his father’s footsteps to begin a military career. William Maurice (Pat) Armstrong was born on 20 August 1889 in Sligo as the eldest child of parents Marcus and Rosalie.

His father, Marcus Beresford Armstrong was born on 19 May 1859 in Ballydavid House, Woodstown, County Waterford. Marcus chose a military career and on 13 March 1886 was granted the rank of Captain in the 8th Brigade, North Irish Division, of the Royal Artillery. On 11 April 1888 Marcus married Rosalie Cornelia (Muz) Maude of Lenaghan Park, Enniskillen, County Fermanagh, and lived with her in Sligo, where Pat, and his sisters Ione, Jess, and Lisalie were born.

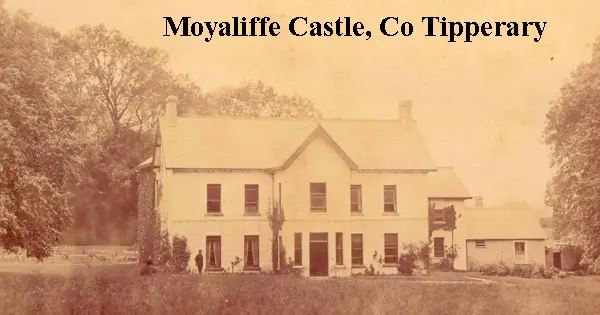

In 1899, Marcus inherited the estates of Moyaliffe Castle, County Tipperary, and Chaffpool House, County Sligo, from his first cousin once removed, Captain Edward Marcus Armstrong, who had died without immediate family. He sold the Chaffpool estate and moved his family to Moyaliffe Castle in 1905. However, some years after the move Marcus and Rosalie became estranged.

In 1914, when the war broke out, Marcus was living alone at Moyaliffe Castle. While Pat’s formative years were spent in Moyaliffe, he was sent to England for his education. He began at Stoke House preparatory school in 1903, from where he was sent to Eton College. Originally known as Maurice, he was given the nickname Pat at Eton. The name stuck, so much so that by 1910 the only person insisting on calling him Maurice was his father.

Pat followed family tradition and entered Royal Military College Sandhurst to seek a career in the army. Having graduated in 1910, he joined the Tenth Royal Hussars and served with that regiment in India and South Africa. In 1914, he decided to seek additional training as a cavalry officer and travelled from Potchefstroom, South Africa, to the Cavalry School at Netheravon, Somerset. He was there when the war broke out.

As befitted a cavalry officer, Pat was passionate about horses and loved hunting, horse racing and polo. He was deeply attached to his sisters and had a special bond with his mother and this is evident in almost all the correspondence between Pat and his family. The letters, diaries, and photographs taken by Pat Armstrong, and the rich tapestry of documents which accompany them, provide a uniquely personal narrative of one Officer’s experience as his genteel Anglo-Irish lifestyle descended to irrevocable decline during War.

After war had been declared on 28 July 1914, efforts to mobilise the British forces began quickly. Although Pat had been assigned as troop leader to the A Squadron of the 18th Royal Hussars, the issue was not fully settled and a degree of uncertainty hung over his future. Eventually, Brigadier General Henry de Beauvoir De Lisle, Commander of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, agreed to ‘smuggle’ Pat out as a permanent orderly officer.

On the morning of 15 August, the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, made up of men from the cavalry regiments of the 4th (Royal Irish) Dragoon Guards, 9th (Queen’s Royal) Lancers, and the 18th (Queen Mary’s Own) Hussars proceeded overseas. Having arrived in France, the British troops, Pat Armstrong among them, proceeded towards Charleroi to join forces with the French Army.

Before reaching their destination, the British Expeditionary Force encountered the advancing German Army at Mons. The British infantry corps was immediately deployed in defensive positions to the east and west of Mons, while the cavalry division was kept in reserve. The size of the German Army had taken the British by surprise and Commander Sir John French had no choice but to order a general retreat.

On 24 August, General De Lisle’s cavalry brigade took over rear guard duties to the retiring infantry and made its way cautiously from Ruesnes to Savy, with many false alarms of advancing German forces along the way. The British troops had suffered 1,600 casualties during the Battle of Mons. Yet, although a British defeat, the conflict had also caused heavy casualties on the German side and bought valuable time for the French and Belgian forces to attempt to form a new defensive line.

Pat Armstrong’s next engagement was at Marne. With heavy casualties on both sides, it was a strategic victory for the Allied forces and put an end to German hopes of invading Paris. It also marked the end of the war of movement and the beginning of the trench warfare which was to characterise the Western Front for the next four years.

14 September saw the commencement of the First Battle of the Aisne, an Allied offensive against the German first and second armies retreating after the First Battle of the Marne. Pat wrote to his mother of how ‘four horses were killed with a shell about an hour ago about 100 yards to my right. We are getting used to it now and don’t bother unless they are actually bursting round one’.

After the First Battle of the Aisne ended on 28 September, the 1st Cavalry Division marched to the zone of operations in West Flanders. The march took a week to complete and was made at night until the troops were clear of the Aisne country. In the daytime, men and horses were kept hidden to prevent enemy aircraft from collecting information about their movements. The Division arrived in Flanders on 11 October, the day after the fall of Antwerp to German troops.

In England, Pat Armstrong’s regiment, the 10th Hussars, who had made their way from South Africa, were preparing to depart for France. Despite Pat’s hopes that the ‘show could not go on for much longer’, this was an intense week for the cavalry on the Western Front with the commencement of the battles of La Bassée (10 October-2 November), Messines (12 October-2 November) and Armentières (13 October-2 November).

For Pat, the week also brought a firmer foothold as a consequence of the formation of a Cavalry Corps of three divisions under the command of General Allenby. General de Lisle was given command of the 1st Cavalry Division, and used the opportunity to formally appoint Pat Armstrong as his aide-de-camp. Pat’s regiment, the 10th Royal Hussars, who had just arrived in France, formed part of the 3rd Division and were billeted near De Lisle’s headquarters.

The war on the Western Front was entering its bloodiest phase yet. The 1st Cavalry Division under Major-General De Lisle continued to hold on to its position on the Messines ridge but suffered substantial casualties. De Lisle’s headquarters came under direct shellfire and had to be evacuated. On 19 October, the First Battle of Ypres commenced with a series of assaults against the city, which formed the last obstacle to the German advance to Boulogne and Calais.

For the next four years, German forces surrounded Ypres from three sides bombarding the city for much of the time, razing virtually every building to the ground. As the fighting intensified, Pat had a near-death experience when his billet was shelled. He wrote to his mother on October 31 describing how the shell had ‘hit the side of the house & burst inside, it flattened the wall down as if it had been made of paper’.

The hope of the ‘show being over before Christmas’ was slowly being ebbed away as the first Battle of Ypres entered its third phase and continued with tremendous violence, the German forces capturing Messines, Hollebeke and Wytschaete and recapturing Neuve Chapelle after intense back-and-forth fighting and a successful piercing of the British lines.

Having fought night and day with utmost tenacity, the British troops were utterly exhausted and rejoiced in the arrival of strong French reinforcements which finally put a halt to the German assault. Dodging shells and bullets, Pat wrote to his mother on 5 November 1914: “I wish it would come to an end as I am heartily sick of the whole show. Some of the German prisoners say that nearly all their officers have been killed or wounded & that the war will be over in two months. Too good to be true I’m afraid. I was told yesterday that it might be over by Xmas but probably March.”

The next day, Pat wrote again to Muz, further detailing his growing discontent: “It is a rotten show & is simply a war of endurance. It’s a war of rats, as soon as one gets a bit of ground you have to immediately dig a deep narrow trench to get into. There is no sort of excitement about it at all & casualties are dreadful.”

In the Second Battle of Ypres the 10th Royal Hussars suffered heavy casualties, including 11 officers. Increasing pressure was put on Pat Armstrong to re-join his regiment. Anxious to fulfil his regimental duty but reluctant to let down General De Lisle, he was caught in an awkward dilemma uncertain how to proceed. An unexpected solution to the problem presented itself when General De Lisle received orders to take command of the 29th Division in the Dardanelles and insisted on taking Pat along.

On 18 March, the British and the French launched an ill-fated naval attack on Turkish forces to gain control over the Dardanelles, a narrow, strategically vital strait which separated Europe from Asia. The disastrous failure of a concerted Allied naval operation made it evident that the capture of the Gallipoli peninsula would not be possible without the help of the army, and preparations to launch a full-scale landing commenced.

On 24 May, General De Lisle was ordered to take over the command of the 29th Division at Gallipoli from Major General Aylmer Hunter-Weston, whose blundering battle plans and blatant disregard of troops gave him a reputation as one of the most brutal and incompetent commanders of the First World War.

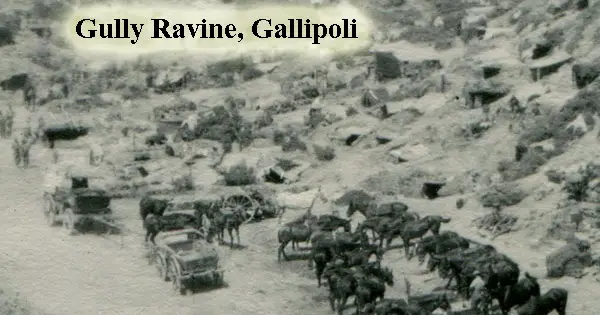

General De Lille charged Pat with the responsibility of overseeing the transportation of the division’s horses to Gallipoli. Pat journeyed from St Omer to Paris to Marseille, on the Elephanta to Port Said and Alexandria. He then continued, from Alexandria to Gallipoli where he arrived on June 24, just in time for the Battle of the Gully Ravine.

Pat was initially fascinated by his new surroundings and wrote of his amazement at the complex nature of the trenches and the camp. He relayed to his mother on 24 June of their ‘great big dug out as a dining room with two big tables & benches in it. It is about as big as Ione’s bedroom. Then we sleep in tents outside rather cut into the face of the hill. We are quite close to the sea & have quite a nice view’.

However, the horrors of Gallipoli came quickly as the severity of his new environment took effect. The intense heat, the flies and insects, and the sandy terrain made even times of peace in Gallipoli challenging; conditions tested the western soldiers physically in ways they had never experienced before.

Men got sick with the “Gallipoli Gallop” (diarrhoea), Pat got it twice so badly that he had to be sent to Athens to recover. Pat was also deeply affected by the ‘masses of dead & wounded & equipment lying everywhere’.

On 30 June, Pat wrote of the Battle of Ravine: “There were dead Turks, dead & wounded men everywhere. I had to cross over a bit of ground which for some time had been a no man’s land. There were several skeletons of our men & Turks lying about. Then I went on & was able to see a little of what our shells can do. Their skeletons were broken down & many of the trenches were knocked to bits. I went on up there & got in touch with our men in the front trenches. It was awfully interesting to see it all but it was dreadful going along the trenches as they were packed with dead & wounded both English & Turk. It was horrid having to step over them & in one place the Turkish dead were so thick that I had to walk on them.”

The Pat Armstrong war story does not end here. His career can be followed through the weekly updates of his letters, diaries and photographs provided by the Special Collections Library, University of Limerick.

By accessing their online project and submitting an e-mail address to the ‘follow’ button on longwaytotipperary.ul.ie, followers will receive weekly posts and can relive the experience of one officer’s journey through the Great War.

history.html