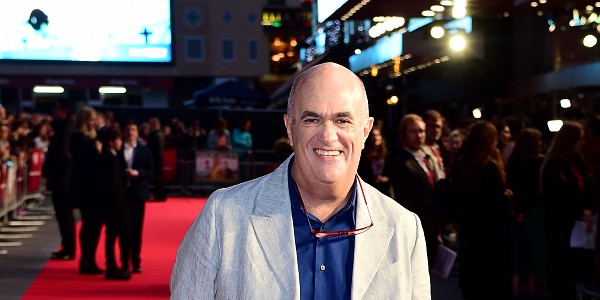

Author Colm Toibin has revealed how stories from his childhood find their way into his work.

The three-time Man Booker nominee, whose novel Brooklyn is tipped for Oscar success, also described how his father Michael’s death when he was 12 continues to influence his writing.

Toibin spoke of his pride when Ireland became the first country in the world to bring in gay marriage last year by way of popular vote.

“It was not a rejection of anything, it was embrace of things. We did not emerge as an angry group demanding rights, we came as somebody’s grandson, somebody’s brother and somebody’s lover,” he said.

Originally from Enniscorthy, Toibin now divides his time between Dublin, London and the United States, but insists he can write anywhere so long as he has a “blank wall, no view and an uncomfortable chair”.

And talking about his life and loves on BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs, the award-winning author also offered some sage advice for aspiring writers – don’t do lunch and don’t worry about other people’s feelings, just write the story and tell them.

Although he has been unsuccessful three times in the prestigious Man Booker award Toibin described how he felt surprised after missing out for his acclaimed work The Master but felt the experiences proved to be ” enabling” and left him feeling free to bounce back.

“Probably if I had won I would have had a big head – actually I would have enjoyed winning and I would have been able to handle it perfectly,” he said.

Selecting music from mainly Irish artists Toibin described the machinations of writing.

“I’m trying to get it written, I’m not trying to amuse myself. Swimming for example is fun, writing is not,” he said.

“I do take an enormous pleasure from things but being in a corner writing is not one of them.”

Many of his childhood experiences resonate in his work today, with Toibin recalling a striking sense of abandonment when his father became ill, developing a stammer and being sent with his brother to be cared for by nuns.

“I think it affected both us very deeply. I find with the novels that a novel is going along great and suddenly I’ll have the character being abandoned by somebody and I’ll find that, oh no, not again, here it comes,” he said.

“Every time there is someone abandoned and it comes up in short stories it really interests me because the emotion remains raw with me.”

Toibin described the emotions and experiences as a form of DNA and that no matter what he tries to write it won’t work unless he gives in.

He put pen to paper almost every day from the age of 12 as a form of relief, beginning with poetry published in a magazine which took work from teenagers.

An uncle discovered his name in print two years later and informed his mother, who Toibin said was “puzzled and proud”.

“Suddenly the guy who couldn’t do anything could do this,” he said.

Gradually Toibin honed his skill into recalling stories from a bank of memories he built listening to his mother, sisters and aunts talk as a child.

Toibin did not discuss his homosexuality with his family, rather they just came to know, he said.

“My mother asked my sister an interesting question at one point, ‘is he happy?’ which is very sweet, but she did not ask me that. We did not talk about it.”

But she was deeply interested in his writing and was alive for his first few major publications.

“She had an interesting way of handling it. She would write me quite serious letters about the style. She’d become interested in fiction herself as she grew older and she was reading Saul Bellow,” he said.

“She thought my novels were too slow.

“And she did not really want to say that to me, but she would say ‘isn’t Saul Bellow marvellous, how smart he is’, meaning ‘is there any chance your novels could become a bit smarter, a bit snappier’. But she was proud and she made that clear.”