One of the many tragic ironies of the Great Hunger in Ireland is that as people died of starvation, thousands of tons of grain that could have saved them was instead shipped out of the country.

How could such a seemingly perverse and inhuman policy be allowed to continue?

Unshakeable belief in Free Trade

The answer lies in the political and economic beliefs of the British ruling classes at the time. The Whig government of Prime Minister Lord John Russell had an unshakeable belief in free trade. They were opposed to anything that would distort the market and damage the balance of supply and demand.

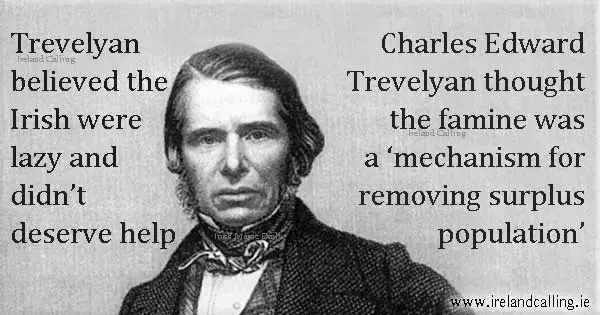

This was an approach enthusiastically enforced by Charles Trevelyan – the Secretary of the Treasury and the man in charge of famine relief in Ireland.

His main priority, far above that of feeding the starving, was that there should be no interference with free trade.

If landowners could earn more for Irish produced grain by selling it in England or in Europe rather than making it available to the destitute in Ireland then so be it.

This caused enormous resentment in Ireland and was even too much to take for some of Trevelyan’s own administrators. In the summer of 1846, the Commissary General Sir Randolph Routh, urged that Irish ports should be closed to prevent the export of grain.

Trevelyan flatly refused and wrote back saying: “Do not encourage the idea of prohibiting exports, perfect Free Trade is the right course.”

“Serious evil” to export food

Routh stood his ground and again insisted that it was essential to close the ports. Otherwise more than 60,000 tons of grain that could be used to feed the starving would instead be shipped abroad. He said was a “serious evil” to export food in the middle of such a crisis.

Trevelyan, with the full backing of the government, would not be moved. He replied: “We beg of you not to countenance in any way the idea of prohibiting exportation. There cannot be a doubt that it would inflict a permanent injury on the country.”

From the outset, the Irish were left in no doubt as to the approach to be taken by Trevelyan. He made his position clear as soon as he came to office by closing down the depots providing maize for the poor which had been set up by the previous government of Sir Robert Peel the year before at the outbreak of the famine.

From the outset, the Irish were left in no doubt as to the approach to be taken by Trevelyan. He made his position clear as soon as he came to office by closing down the depots providing maize for the poor which had been set up by the previous government of Sir Robert Peel the year before at the outbreak of the famine.

He wanted there to be no free hand-outs to the poor.

Trevelyan increased public works

Instead, he increased the public works projects, ensuring that that the starving would have to work to earn some money if they wanted to be fed. These work projects were carefully designed so they did not interfere or compete with private enterprise. Therefore they were confined to areas such as building roads and walls, or repairing fences – the kind of projects that would not interest businesses as they would not be sufficiently profitable.

All these works were financed out of local Irish taxes. The cost to the central Treasury was to be kept to a minimum.

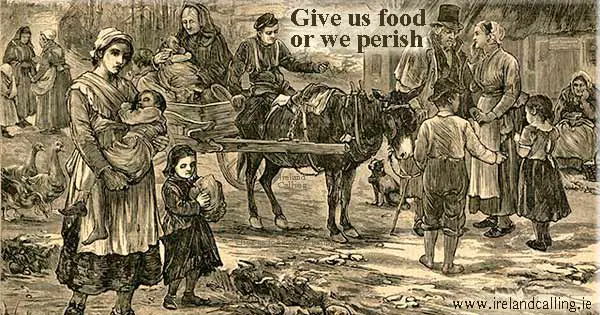

As the death toll mounted in September and October, the clamour for the government to provide more help grew so strong it could no longer be ignored. The Belfast newspaper the Vindicator captured the national mood in this article published on 3 October 1846.

“Give us food or we perish,” is now the loudest cry that is heard in this unfortunate country. It is heard in every corner of the island – it breaks in like some awful spectre on the festive revelry of the rich – it startles and appals the merchant at his desk, the landlord in his office, the scholar in his study, the minister in his council room, and the priest at the altar.

“Give us food or we perish.”

It is a strange popular cry to be heard within the limits of the powerful and wealthy British Empire. Russia wants liberty, Prussia wants a constitution, Switzerland wants religion, Spain wants a king, Ireland alone wants food.

Trevelyan reluctantly tried to help

Trevelyan reluctantly accepted that something would have to be done, although his heart wasn’t really in it. He tried to buy corn abroad as Sir Robert Peel’s government had done the year before with admirable haste, but it proved hard to find. The European harvest had been low that summer and there was very little surplus available. America had supplies but attempts to ship it to Ireland would be hampered by the coming winter which would freeze the trade lines of the American rivers.

Severe winter increases death toll

In the meantime, the public works schemes designed to give the poor the chance to earn money for food were running into difficulties. There were delays in getting them started due poor administration and once they did get going there were further delays due to lack of equipment and skilled engineers to oversee the work.

Then, as everyone thought things could surely get no worse, one of the severest winters for years set in. To add to the death toll from hunger, and famine related diseases, many labourers on the public works schemes collapsed and died from exposure.

Meanwhile the government continued to dally, the starving continued to die, and the ships laden with oats, wheat and barley continued to sail out of Irish ports.

The potato crops may have failed yet Ireland was producing vast amounts of other food that could have been used to save the dying. Instead, it was shipped out of the country to be sold for profit in England.

The Irish Famine – the Great Hunger

An English View of the Irish Famine