The Great Famine of the late 1840s is the single most catastrophic event in Irish history. It caused a million deaths and forced a million people to emigrate.

It changed Ireland forever and cast a shadow over the country for the next 150 years. It also had a profound effect on other countries like America, Australia and the UK because of the mass migration it caused.

Although the disease that wiped out the potato crop was a natural phenomenon, most historians now agree that the resulting famine was largely man made because of government incompetence and even wilful neglect. Some officials at the time even regarded the famine as God’s way of getting rid of excess population.

There had been several failures of the potato crop in Ireland in the 17th and 18th centuries which led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

However, the period now referred to as the Great Famine (An Gorta Mór in Irish) began in September 1845.

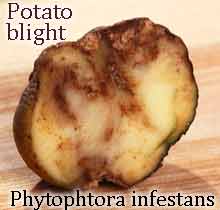

There had been warning signs since June that year when the potato crop in Belgium and other mainland European countries was found to be infected with a strange new blight which we now know as phytophthora infestans. It reduced healthy potatoes to stinking inedible pulp.

In Europe, the crop failure was a serious but manageable problem; in Ireland it was a disaster on an unprecedented scale. There were two reasons why the Irish suffered so much more than people on the continent.

The best land was owned by wealthy English lords

First, for historical reasons, more than two million Irish labourers and their families were totally dependent on the potato to survive. This was much higher proportion than in other countries.

Second, the British government at the time was not prepared to fund famine relief and follow the steps taken in mainland Europe to prevent mass starvation.

The reason so many Irish poor relied on the potato was due to the issue of land ownership. The English conquest of Ireland meant most of the best land was in the hands wealthy landlords, many of whom were either English or of English descent.

Many of them were known as absentee landlords because they didn’t even live in Ireland.

Most of these people, even those who lived in Ireland, still regarded themselves as British and had little empathy with the native Irish. They owned most of the best land, and their main concern was to make a profit from cash crops like wheat or by raising cattle.

The Irish were confined to the less fertile land. Their smallholdings were divided up between sons so that by the 1840s, most of Ireland’s poor depended almost entirely on what they could grow from small plots of second rate land. Some of these plots were little more than an acre.

The only crop that could provide enough food to support a family on such small plots was the potato. By the 1840s, more than two million people depended on it as their life support system. Even when times were good, they struggled to survive; if the crop failed they knew they faced starvation.

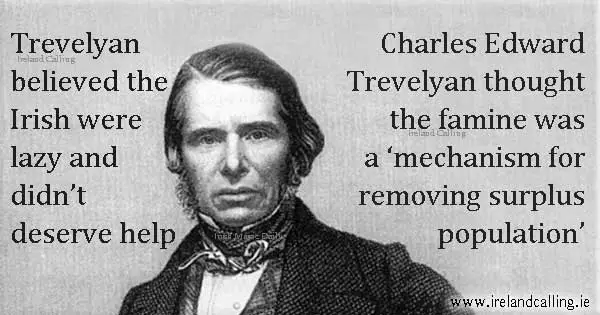

Trevelyan thought famine was God punishing the Irish

The reason the government failed to provide sufficient famine relief was due to political and economic philosophy, and perhaps a little religious prejudice.

When the famine first struck in 1845, the British government was headed by Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel. He had experienced crop failures in Ireland before and set about importing grain from abroad to help feed the starving. He also started to set up public works projects so the poor would have a way to earn money to buy food.

Unfortunately for the Irish, Peel lost the 1846 election and the Whig party led by Lord John Russell came into power.

The Whigs believed in the free market and opposed anything that would upset trade. They were also evangelical Protestants with little respect Irish Catholics. Some regarded Ireland as a backward country with an idle population and outdated farming systems.

Charles Trevelyan, the man responsible for organising famine relief in Ireland, even went to so far as to say that the famine was God’s way of punishing the Irish and weeding out excess population.

Taken together, these views had disastrous consequences for the Irish poor because it meant the way the British government handled the crisis was in stark contrast to how governments in mainland Europe reacted.

When the potato crop failed in Belgium, the government there stopped the export of food products such as grain and livestock. The British government was urged to do the same but it refused on the grounds that banning food exports would interrupt free trade and be bad for the economy.

The result was that as the poor starved. Millions of tons of grain and livestock that could have been used to feed them was instead shipped abroad to be sold for profit, mainly in England.

Historians disagree about whether or the not the food that was exported would have been enough to have prevented the famine entirely, but all are agreed that it would have been enough to have saved at least hundreds of thousands of lives.

The potato crop didn’t fail in 1847 but that was of little help as the poor had been forced to eat their seed potatoes over the previous year and so hardly any crops had been sown. Nevertheless, the government declared the famine to be over and stopped public works programmes.

Ministers relented over the following years as the crops continued to fail and the death toll mounted.

The government set up soup kitchens, which did succeed in saving many lives. It also introduced more public works programmes but they were poorly organised and largely ineffective.

Ireland lost a quarter of its population

The potato crop continued to fail in varying degrees until 1851. There were more failures afterwards but the worst period, the one referred to as the Great Famine, occurred between 1845 and 1851.

During that period an estimated one million people died of starvation or famine related diseases such as typhus and dysentery. A million more emigrated during or immediately after the famine years.

Ireland was left devastated. It lost a quarter of its population in the space of six years. The government’s role in denying help to the starving has led many commentators to describe the famine as Ireland’s Holocaust.

The famine, its causes and consequences, are still widely researched and debated today, and it still evokes an emotional response of anger and bitterness among

Irish people, and among those of Irish descent whose ancestors were forced to emigrate to countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia and the UK.

The links below will take you to several more articles that explore different strands of the famine, the great watershed event in Irish history.

The Irish Famine – the Great Hunger

More than a million people died and another million emigrated because of the famine in Ireland in the late 1840s. But it wasn’t just a natural phenomenon. Increasingly, it is being seen as genocide by incompetent and callous government officials.

Be a friend of Ireland Calling

Falling income due to Covid is threatening our ability to bring you the best articles and videos about Ireland. A small monthly donation would help us continue writing the stories our readers love. As a thank you, we’ll email you a free gift each month you donate.

More Famine Videos

An English View of the Irish Famine

English TV reporter Mike Nicholson wanted to write a book showing that the British government had been unfairly blamed for causing the deaths of a million people by mishandling the Irish famine. But the more he researched what happened, the more he changed his mind.

Tom Guerin – the Boy Buried Alive

Tom Guerin was only three years old when he was buried alive in a mass grave in Abbeystrewry near Skibbereen. Such mistakes were not uncommon in hastily arranged burials during the famine in Ireland in the 1840s.

Why Food Was Exported During the Famine

The potato crops may have failed yet Ireland was producing vast amounts of other food that could have been used to save the dying. Instead, it was shipped out of the country to be sold for profit in England.

The Doolough Tragedy Video

During the Irish Famine, hundreds of desperate, starving people were forced to walk 12 miles through the cold and rain at night to get help. Many died on the way.

The Deserted Vlllage of Achill Island

This deserted village on Achill Island is a sad reminder of the most tragic event in Irish history…the Great Hunger of the 1840s, sometimes referred to as the Irish Holocaust, such is the emotion it evokes.