The repeated failure of the potato crop in the 1840s was a natural disaster but the famine that followed was almost entirely man made.

That is a view now widely accepted by most historians who have studied the period closely – a period that saw one million die of starvation and led a further two million to emigrate. But if the famine was man-made, who was to blame and what should they have done to prevent or at least reduce the suffering caused by the crop failure?

British government failed to take necessary action

The British government bears most of the responsibility for failing to take the action needed to prevent starvation and the loss of life on a scale never seen before.

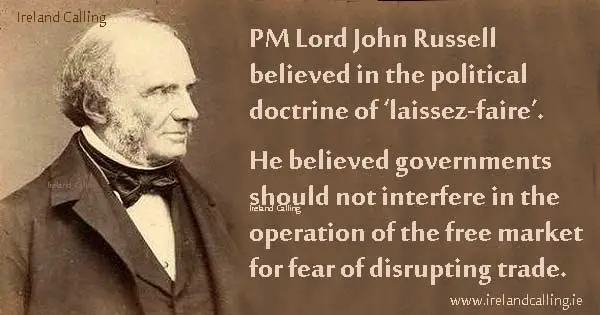

The party in the power at the time, the Whigs led by Prime Minister Lord John Russell, believed in the political doctrine of laissez-faire, which advocated that governments should not interfere in the operation of the free market for fear of disrupting trade and preventing prices finding their own true level.

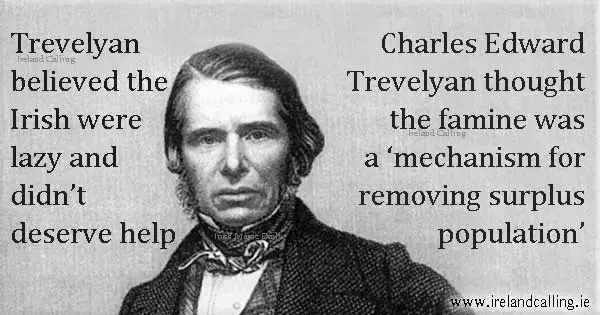

They also believed the Irish were mainly to blame for their plight because they had outdated and inefficient farming systems. Many believed the Irish were lazy and didn’t deserve help.

Some civil servants like Charles Trevelyan even believed that the famine was God’s way of ridding Ireland of excess population. It would therefore be sinful to interfere and help the Irish as that would be thwarting God’s will.

This was a dangerous belief considering that Trevelyan was the man appointed to oversee the famine crisis. True to his beliefs and those of his colleagues in the Whig Party, Trevelyan did little to provide food and help for the starving.

So what should he and the government have done? The historian James Donnelly in his book, The Great Irish Potato Famine, has identified six key strategies that could have alleviated the suffering and saved hundreds of thousands of lives.

1. The government could have prevented Irish wheat and barley from being exported once it was clear that the potato crop had failed. It was advised to do so by its own officials including Sir Charles Routh who urged that the ports should be closed so food could not leave the country.

The government refused for fear of distorting the market. It meant that grain that could have been used to feed the starving was instead exported to maintain the profits of wealthy merchants and landowners.

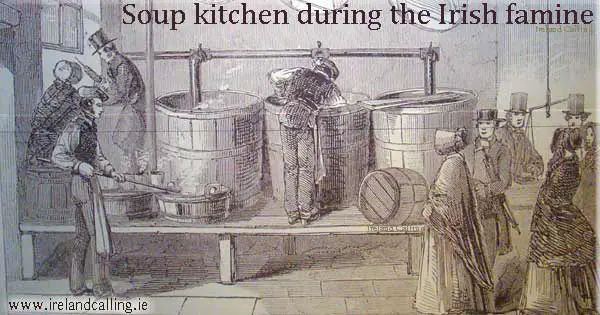

2. The soup kitchens should have stayed open much longer. The kitchens were only in operation for about six months between March and September 1847.

During this time they were able to feed up to three million people cheaply and effectively. They were closed down even though the potato crop failed again in 1847.

3. The government introduced a series of public works to enable the poor to earn money to buy food. However, the wages were too low and should have been increased significantly so that labourers could afford the escalating food prices.

4. The poor law system, which provided relief for the destitute in various way but most notably within workhouses, needed to be less restrictive. Numerous bureaucratic obstacles were used to avoid giving generous relief to the starving. Again, the reason was to keep down costs and to promote self-reliance.

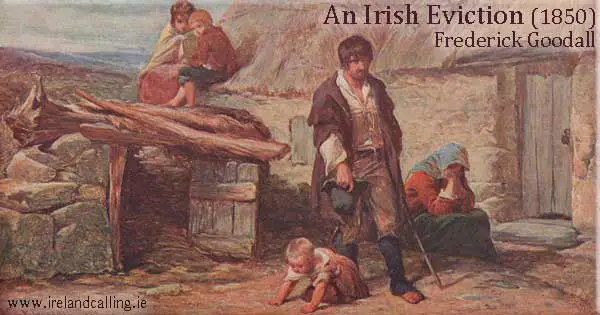

5. The government could have stopped landlords evicting tenants from their homes because they were unable to pay their rents due to the crop failures. Donnelly estimates that up to 500,000 people were evicted between 1846 and 1854.

6. Finally, the government should have accepted the famine crisis as a responsibility of the British Empire and been prepared to bear the costs of providing help.

Instead, it treated the crisis as a local Irish issue that the Irish themselves should pay for, something they were clearly unable to do under the circumstances because most of the country’s wealth was in the hands of British owners.

The government, of course, did none of these things regardless of how the death toll mounted.

Deserted Village of Achill – victim of the Irish Famine Holocaust

Great Famine ‘should be taught’ in California schools

Cork statue pays tribute to Choctaw tribe’s generosity during Irish Famine