The Easter Rising may have erupted suddenly in 1916 but it had a background of Irish discontent with British rule that dated back several hundred years.

There had been numerous rebellions in the past, starting with the Irish Bruce Wars of 1315-18, which saw Irish chieftains trying to overthrow the English monarchy and install Edward Bruce from Scotland as king. They failed, as did many more generations of Irish rebels right up to the 19th century. Some of these outbreaks, such as the Jacobite War of 1689-91 involved substantial armies and major battles. Others like the Rebellion of 1798 saw heavy fighting involving ordinary citizens rather than professional troops. Many more ‘uprisings’ like the Emmet Rebellion of 1803 were little more than minor skirmishes, put down by the British before they had hardly begun.

Why did the Irish keep on rebelling against Britain

Yet no matter how many times these rebellions were defeated, the Irish kept coming back for more, generation after generation. The question has to be why. Why didn’t the Irish accept British rule like their Celtic cousins in Scotland and Wales?

The answer, at least in part, lies in the way succeeding British governments had dealt with Ireland. There was a long history of removing Irish Catholics from their lands and replacing them with Protestant settlers from England and Scotland, most significantly under James I and the plantation of Ulster, and by Oliver Cromwell after the Irish Rebellion of 1641. There were penal laws in place meaning Catholics could not vote, hold key government offices or practice certain professions.

The 1798 Rebellion, although unsuccessful, alarmed the British who decided to abolish the Irish parliament and govern directly from London. The Act of Union of 1801 meant Ireland would now send about 100 MPs to the new United Kingdom parliament of England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The union flag was created, comprising of elements drawn from the flags of the four countries. At this time, the majority of Catholics and Protestants in Ireland were in favour of the Act of Union.

The Protestants felt safer being part of an overall Protestant majority in the UK, than they did being an elite minority in Ireland alone.

For their part, the Catholics were enticed by the promise that the penal laws would be abolished once Ireland was fully embedded in the UK. However, King George III refused to agree to Catholic Emancipation in Ireland, believing that it would betray his coronation oath to uphold the Protestant faith. Catholics felt betrayed and it took years of campaigning by one of Ireland’s greatest ever leaders, Daniel O’Connell, to get the penal laws repealed in 1829…albeit that it only really benefited the middle classes.

There were other grievances, such as the way Catholics had to pay tithes (a kind of tax) to fund the Protestant Church of Ireland, and the way the government held a veto over the appointment of Catholic bishops.

The Great Hunger helped fuel nationalist feeling

Then came the Great Hunger, or famine of 1845-1851 – the cataclysmic event that changed Ireland forever. Given that it led to a million people leaving Ireland within a few years, it also had a major effect on countries like America and England.

Ireland wasn’t the only country struck by potato blight during those years, but it was the only country to be totally devastated by it. A million people died of starvation and disease, and as many more emigrated.

The blight was a natural disaster but the Irish considered that the ensuing famine was entirely man made. They blamed the British government and landlord classes. It was the British government that had driven poor Catholics off their land and given it to English landlords, many of whom never even visited Ireland.

Millions of Irish were left to eke out a living on inferior ground, forced to survive almost entirely on potatoes because they could not afford anything else. Yet throughout the famine years, the country produced vast supplies of grain and animal products. Most of this was shipped out of Ireland, even as thousands begged for food, because the government did not want to interfere with market forces.

Britain’s leading administrator for Ireland, Charles Trevelyan, even went so far as to say that the famine was God’s way of removing Ireland’s surplus population. This kind of indifferent attitude during the famine years caused huge resentment and helped to fuel Irish nationalism, which was already gathering pace anyway. The Young Irelanders emerged at this time and planned another rebellion. Although it was infiltrated by the British and was defeated before it had hardly begun, it was a harbinger of things to come.

A Nation Once Again became a rallying call

One of the Young Irelanders at that time, Thomas Davis, wrote the song, A Nation Once Again, which became hugely popular as a rallying call with the refrain, And Ireland long a province be, a Nation Once Again.

The Fenian Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa pointed out that Ireland exported enough food during the famine to have fed all its people easily. This became a widespread belief in nationalist circles, and although modern historians have described it as an exaggeration, there’s little doubt that hundreds of thousands of lives could have been saved if Ireland had not been forced to export its food.

O’Donovan Rossa died the year before the Easter Rising but he still had a major influence on what happened. He became a founding member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, formed in 1858 by James Stephens to fight for Irish independence.

Rossa helped to plan what became known as the Dynamite Campaign, in which a young IRB member called Tom Clarke and others set about bombing key targets in London to force the issue of Irish independence on to the political agenda. Clarke was to spend 15 years in prison for his efforts but that didn’t stop him. He went to become first signatory to the Proclamation of Irish Independence in 1916.

Even before the Great Hunger, O’Connell and others came to see Irish home rule as the only way to secure justice and prosperity for Ireland. O’Connell died in 1847 but the torch would soon be picked up by the next generation.

On 1 September, 1870 the Home Government Association was formed by Isaac Butt, a lawyer and former MP. Butt was a Protestant, showing that a desire for Irish self-government was non just a Catholic project. Butt wasn’t looking for full independence, just an Irish parliament that would run Irish affairs better than London. The British parliament would still remain sovereign, especially over foreign affairs.

Parnell headed the campaign for Irish Home Rule

By 1880, Butt’s organisation had been renamed the Home Rule League and he was replaced as leader by another one of Ireland’s great charismatic figures, Charles Stewart Parnell. Like Butt, he was also a Protestant and he went on to wield huge power and influence, so much so that he became known as the uncrowned king of Ireland.

Parnell had become president of the Land League in 1879, an organisation set up by Michael Davitt to overthrow the landlord system in Ireland. They began what became known as the Land War, which involved opposing the evictions of poor tenants. Landlords guilty of unjust evictions faced the threat of attacks, both on themselves and their livestock. Anyone taking over the farm of an evicted tenant would be boycotted – the term boycott was coined at this time, after the treatment given to the land agent Captain Charles Boycott.

British Prime Minister William Gladstone eventually conceded to the demands of the protesters and the Land Act was passed in 1881. It gave the farmers the three F’s they had been looking for: free sale so they could sell their tenancy if they wished subject to certain conditions, fair rents to be set by independent tribunals, and fixity of tenure to give tenants greater security.

Discontent continued and there were still grievances but the Land War had shown that the people could have an effect on the British government and force it make concessions. Meanwhile, the campaign for Home Rule gathered pace under Parnell.

A bill was twice put forward by Gladstone and was defeated on each occasion, but most campaigners believed that it was only a matter of time before it was conceded.

Gaelic Athletic Association and Gaelic League formed

Meanwhile, there were other developments that were to have a profound impact on Ireland. In 1884, the Gaelic Athletic Association was set up to preserve and promote traditional Irish sports. It proved instantly popular but denied membership to the police and army, setting it apart from the established authority right at the outset. It was soon infiltrated by the IRB who saw it as a good recruiting ground.

In 1893, the Gaelic League was formed by history professor Eoin MacNeill and others, including Douglas Hyde who became its first president. Its purpose was to promote the Irish language and culture. Like the GAA, it wasn’t overtly political but it helped to foster a sense of Irish identity that was to be important in the future. It also gave a voice to a young man called Patrick Pearse, who would go on to play a pivotal role in the Easter Rising.

As Ireland entered the early years of the 20th century it had gained some concessions such as the land reforms but there was still a long way to go. John Redmond had become the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party and continued the campaign for Home Rule.

Meanwhile, other nationalist forces were coming together and they had a different take on Irish self-determination. They weren’t interested in the compromise approach offered by Home Rule, which would provide Ireland with its own parliament but still leave it as part of the British Empire and subject to ultimate British control. They wanted full independence.

Chief among these forces was the Irish Republican Brotherhood. It had been in decline in the late 19th century but still contained committed nationalists, among them Tom Clarke, the veteran of the London dynamite campaign. He still had ambitions for an independent Ireland and began reviving the IRB, recruiting energetic young members like Sean MacDiarmada.

Patrick Pearse also came on board. Together these men began to think of rebellion as a way of achieving Irish independence once and for all. They were conscious that rebellions had failed in the past but this time they believed the outcome would be different.

Britain’s difficulty was Ireland’s opportunity

They believed there was a unique set of circumstances that had never come together before.

The most obvious change was that Britain was at war with Germany. Many rebel leaders felt that Britain’s difficulties would be Ireland’s opportunity. They reasoned that with a war to fight in Europe, the British would have neither the will nor the manpower to suppress a rebellion in Ireland.

This belief was strengthened by the fact that the British Government had already promised Home Rule for Ireland. Following persistent political pressure from Irish nationalists like Charles Parnell in the 19th century, British resistance to the idea of Irish Home Rule had weakened.

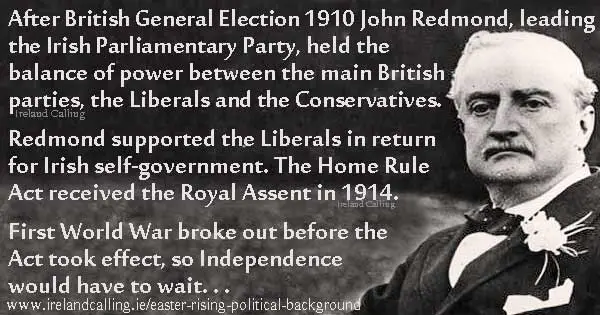

Matters came to a head after the British General Election in 1910 when the Irish Parliamentary Party, led by John Redmond, found it held the balance of power between the main British parties, the Liberals and the Conservatives, in the British Parliament.

Redmond agreed to back the Liberals but exacted a high price; in return for the support of Irish MPs, Redmond demanded self-government for Ireland. The Liberal Government relented and the Home Rule Act received the Royal Assent in 1914.

Home Rule was postponed because of the war

The First World War broke out before the Act could take effect but the commitment had been made. Redmond and most nationalists, albeit reluctantly, accepted that Home Rule would have to wait until the British had dealt with the more pressing matter of winning the war.

Buoyed up by the promise of self-government, the Irish then threw their energies behind the war effort. More than 200,000 Irishmen fought in the British army. Some were patriotic to the Crown at that time; others believed that if they helped Britain in its hour of need, it would reward them with Home Rule. Many more just needed a job.

200,000 Irish fought for Britain in war

Many Irish nationalists, however, including the IRB leaders like Pearse and Clarke, did not trust the British to keep their word. Nor did it matter to them very much anyway as they did not want Home Rule; they wanted an independent republic.

Ironically, they felt the Home Rule issue may have provided them in a roundabout way with the troops to stage a rebellion. The Protestant community in the North were bitterly opposed to Home Rule and under the leadership of Edward Carson, they formed the Ulster Volunteer Force to fight against it.

This prompted Eoin MacNeill to suggest there should be an Irish Volunteer Force to do exactly the opposite and fight in favour Home Rule. The Irish Volunteers were formed in 1913 and had attracted an estimated 160,000 members by 1914. The vast majority of them took Redmond’s advice and decided to join the British Army and fight against Germany, but about 11,000 refused and remained in Ireland.

The IRB leadership believed these Volunteers could be used to provide the military might for a rebellion.

Meanwhile, James Connolly, the socialist leader of the Transport and General Workers Union was contemplating a rebellion of his own. He thought it was the only way to achieve justice for the working class of Ireland. The union had set up the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) to protect trade unionists from police brutality during demonstrations and strikes. Connolly planned to use the ICA to strike against the British.

Pearse met with Connolly in January 1916 and persuaded him it would be better if they pooled their resources. He agreed and was drafted on to the IRB’s Military Council, comprising of Pearse, Tom Clarke, Sean MacDiarmada, Thomas MacDonagh, James Plunkett , Éamonn Ceannt, and finally Connolly himself.

They believed they had the will, the manpower and a unique opportunity in that Britain was preoccupied with the war. Together they planned the Easter Rising 1916. It was an event that would eventually transform Ireland, although at first it appeared to have been a total failure.

easter-rising.html