The British reacted quickly to crush the Easter Rising and then moved just as quickly to punish those who had dared to take part. From an Irish nationalist point of view, the rebels were freedom fighters engaged in a just campaign to gain independence for their country.

From a British loyalist point of view, they were traitors who had tried to overthrow a lawful government. The anger was multiplied by the belief held by many that Germany had been behind the Rising. This was completely untrue but it helped to fuel the sense of outrage, both in Britain and among many people in Ireland.

British Government declared martial law in Ireland

On April 26, at the height of the Easter Rising, the British Government declared martial law in Ireland and appointed Major-General Sir John Maxwell as Commander-in-Chief. Martial law gave Maxwell the power to try the rebels in military courts and impose the death penalty. It was a power that Maxwell was only too willing to use.

He didn’t just want to crush the rebellion; he wanted to extinguish any remaining flicker of Irish nationalism. He felt the best way to do that was by fear. He wanted the Irish to know they faced the full weight of British force if they stepped out of line again.

He declared his thinking in this statement:

“In view of the gravity of the rebellion and its connection with German intrigue and propaganda, and in view of the great loss of life and destruction of property resulting therefrom, the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, has found it imperative to inflict the most severe sentences on the known organisers of this detestable rising and on those Commanders who took an active part in the actual fighting which occurred. It is hoped that these examples will be sufficient to act as a deterrent to intriguers, and to bring home to them that the murder of His Majesty’s liege subjects, or other acts calculated to imperil the safety of the Realm, will not be tolerated.”

More than 3,000 Irish citizens arrested and jailed

Maxwell was quick to put his policy into practice and ordered the arrest of more than 3,400 men and 79 women who were suspected of being involved in the Rising. More than 1,800 were sent to internment centres at Frongoch in Wales.

However, the harshest treatment was reserved for those who had organised the rebellion. A total of 190 men and one woman were tried by military courts. The verdict in 90 of the cases was execution by firing squad.

Maxwell had the final say. He confirmed the death penalty in 15 cases, including all of the men who had signed the Proclamation read out at the General Post Office by Patrick Pearse, declaring that the arrival of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Ireland.

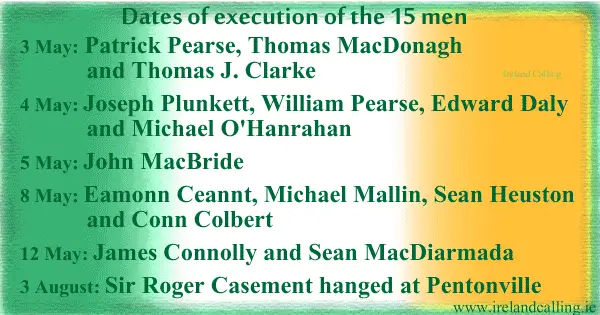

Fourteen men were executed by firing squads between May 3rd and 12th in 1916, only a few weeks after the Easter Rising took place. Click the links to find out more about each man.

They were:

May 3 Patrick Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh, Tom Clarke

May 4 Joseph Plunkett, William Pearse, Edward (Ned) Daly, Michael O’Hanrahan

May 5 John MacBride

May 8 Éamonn Ceannt, Michael Mallin, Sean Heuston, Con Colbert

May 9 Thomas Kent at Cork Barracks

May 12 James Connolly, Seán MacDiarmada

August 3 Sir Roger Casement hanged at Pentonville Prison on 3 August.

Eamon de Valera spared as public opinion shifts

Most people in Ireland had been hostile to the Rising at first, seeing it as unnecessary because the British had already promised Home Rule. They were also angered by the loss of civilian life and the destruction of major buildings in the city centre. The fact that the British, together with leading Irish politicians like John Redmond, put out statements saying Germany was behind the Rising also fuelled public hostility.

However, as each execution took place, public opinion began to change. People started to learn more about the leaders and their motives. They realised that far from being puppets of Germany, they were idealists who were willing to sacrifice their lives for their belief in the need for an independent Ireland. Many were also moved by the quiet and dignified way in which the leaders faced their execution; refusing to blame the soldiers about to shoot them and in some cases even being prepared to pray for them.

Some of the executions evoked particular sympathy, like the death of Joseph Plunkett only hours after marrying his fiancée Grace Gifford in Kilmainham Gaol. The fact that the wounded James Connolly was so weak that he had to be tied to a chair in order to be shot also outraged people in Ireland and around the world.

Irish politicians like John Dillon were quick to gauge the shift in public opinion and urged British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith to rein in Maxwell before he turned everyone into a rebellious nationalist. Asquith agreed and Maxwell was instructed to reduce the number of executions and preferably end them altogether.

One of the first to be spared by Maxwell was Eamon de Valera even though he had played a major part in the insurrection. He was due to be executed on 9 May but the sentence was commuted. It’s not clear whether the reason was the acceptance that leniency was the best policy, or whether the British felt they could not execute de Valera because he was an American citizen. He was born in New York to an Irish mother and a Spanish father. De Valera would later become President of Ireland once independence was established.

Maxwell insisted on going ahead with the executions of Connolly and MacDiarmada on 12 May because he considered them to be among the worst of the leaders. Everyone else, however, had their sentences commuted to interment. The only exception was Sir Roger Casement who was hanged at Pentonville Prison on 3 August.

Events would soon show that Maxwell’s harsh approach backfired completely. Instead of removing the move towards nationalism, it had the opposite effect and increased it. The main beneficiaries were Sinn Fein, who had nothing to do with the Rising but inherited the nationalist fervour that it created. Far from being the man who subdued Ireland, Maxwell later realised that he was the man who had lost Ireland.