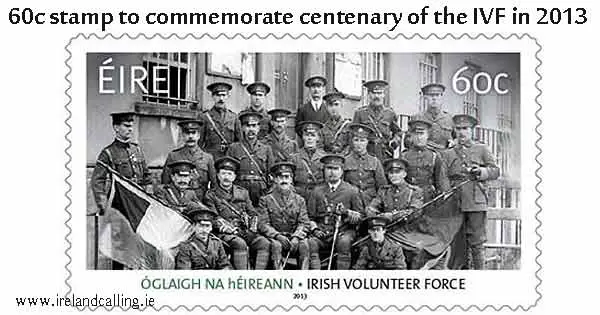

The Irish Volunteer Force (IVF) was created in 1913 to add some military might to the campaign for Home Rule for Ireland. Within a year it had an estimated 160,000 members, but quickly split at the outbreak of World War One. Many joined the British Army to fight against Germany, but a minority refused to enlist and went on to fight in the 1916 Easter Rising.

In 1913, Irish politicians were in the middle of yet another attempt to achieve Home Rule for Ireland. Charles Stewart Parnell had managed to get the British government to put forward Home Rule bills in the 19th century but both were defeated. Now the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), under the leadership of John Redmond, was mounting another push. This campaign was opposed by Protestants who had a substantial majority in some of the counties in Ulster.

In January 1913, prominent Ulster Protestants Edward Carson and James Craig formed the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) to resist any attempt by Britain or the Irish Parliamentary Party to impose Home Rule on Ireland. They feared they would be swallowed up in a hostile Catholic Ireland if that was allowed to happen.

On 25 November 1913, Eoin MacNeill, a moderate and mild-mannered history professor and Gaelic League member, wrote an article in the Gaelic League paper, An Claidheamh Soluis.

The article was entitled The North Began and it urged nationalists to form a similar organisation to the UVF but with the exact opposite purpose – to promote Home Rule for Ireland and fight for it if necessary.

The article had a major impact. Members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) read it with great interest. They were planning a rebellion but lacked the soldiers to make it happen. They felt an Irish Volunteer force could fill that gap.

IRB members encouraged MacNeill to take matters further and see his idea through. They didn’t reveal that they were with the IRB, nor did they mention any plans for a rebellion.

Michael O’Rahilly, most often referred to as the O’Rahilly, organised an inaugural meeting at Wynn’s Hotel in Dublin and the Irish Volunteer Force was born, with Eoin MacNeill as its Chief of Staff. Recruiting posters were produced urging young men to ENROL UNDER THE GREEN FLAG and then “Get a gun and do your part”. It struck a chord with young nationalists who flocked to join, boosting membership to an estimated 160,000 within a year.

Irish MPs held balance of power in parliament

Meanwhile, the Home Rule campaign had been gathering pace. The 1910 General Election in Britain had produced a hung parliament, with neither the Conservatives nor the Liberals having the majority that would enable them to form a government. It meant that John Redmond and the IPP held the balance of power.

Redmond offered his support to the Liberals but demanded that they provide Home Rule for Ireland in return. It should be remembered that Home Rule in this context did not mean independence. Redmond simply wanted an Irish parliament to run Irish domestic affairs. Britain would retain overall sovereignty and control over foreign affairs.

The Home Rule bill was introduced in 1912, to the delight of the IPP but to the utter dismay of the Ulster Protestants who were outraged at the prospect of being subject to a Catholic administration in Dublin. At first, Redmond and British politicians thought the opposition in Ulster would quickly fade away, but it didn’t.

Irish leader was suspicious of volunteers

The country therefore polarised with the Ulster Volunteer Force determined to fight to oppose Home Rule and Irish Volunteer Force equally determined to fight to achieve it. Redmond was suspicious of the IVF at first because he knew it had been infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

He was opposed to violence, even for the purpose of achieving Home Rule. In fact, although he helped navigate the Home Rule Bill through Parliament, he didn’t want full independence – just greater self-rule without breaking the connection with Britain completely.

He saw no value in Ireland severing ties with the British Empire given that hundreds of thousands of Irishmen had fought, and in many cases died, to create it.

This was later to put him at odds with other Irish nationalists, but in 1914 those nationalists valued his support. To overcome Redmond’s doubts about the IVF, MacNeill allowed him to nominate half the seats on its organising committee in June 1914. This was enough to overcome his doubts and he gave the organisation his support.

Volunteers split at the outbreak of First World War

The Home Rule Bill, was officially passed as the Government of Ireland Act and received the Royal Assent making it law on 18 September 1914. It meant Home Rule was to become a reality, although the situation in the north was still unresolved. However, the outbreak of war changed everything. The British Government said the Act would have to be suspended for the duration of the war and Redmond accepted their assurances that it would be implemented once peace was restored.

He saw this as no more than a few years delay and urged Volunteers to enlist and fight on the side of the British Army. MacNeill and the IRB were opposed to this but most of the Volunteers followed Redmond’s advice and about 40,000 enlisted.

However, a small group of more militant members remained. There were only a few thousand at first but their numbers had grown to 15,000 by early 1916. These were the men the leaders of the Easter Rising thought could provide the firepower to force through Irish independence.

Leaders were split over their approach to rebellion

However, there were potentially dangerous differences in the way the leadership of the Volunteers and the leadership of IRB viewed any potential rebellion. MacNeill and most of those around him like the O’Rahilly believed a rebellion should only take place if it had a reasonable chance of success, or if the British forced their hands by trying to outlaw them or perhaps, introduce conscription into the British Army.

The more radical IRB leadership, including Patrick Pearse and Seán MacDiarmada, were ready to contemplate a rebellion at any cost. They even went so far as to suggest that martyrdom or a “blood sacrifice” might be needed to achieve their aims of an independent Ireland.

These different attitudes were to prove fatal at the outbreak of the Easter Rising.

MacNeill was prepared to support a rebellion but only if there were enough troops who were sufficiently armed. It was felt that about 15,000 men could be mustered from the Volunteers and the recently formed Irish Citizen Army. That might be enough to at least get a rebellion started, with more recruits joining in once they saw the action was underway. Britain was pre-occupied with the war effort and might not be able to spare enough troops to stop the rebellion.

That was all highly speculative but the more immediate problem was the lack of arms. The solution was to get Sir Roger Casement to arrange a shipment of arms to be smuggled in from Germany.

MacNeill in particular thought these arms were essential if a rebellion was to have any chance.

Arms for the Rising were intercepted by the British

As it turned out, the ship carrying the arms, the Aud, was intercepted by the British off the coast of Kerry. Casement was later arrested. It meant that the firepower needed to stage a rebellion was lost.

MacNeill was not prepared to go ahead under those circumstances, yet he suspected that the IRB Military Council, of which he was not a member, was plotting behind his back. He insisted that all orders relating to the Volunteers should be countersigned by him.

In order to try to keep MacNeill on board, the IRB forged a document suggesting the British were about to clampdown on the nationalists.

There were several meetings between the two sides with MacNeill eventually discovering that a rebellion was being planned without his approval. He was prepared to go ahead with it at first but reacted furiously when he discovered the document had been a forgery, and that the arms aboard the Aud had been lost.

On Easter Saturday, the day before the Rising was due to begin, MacNeill pulled out. He sent out an order telling the Volunteers to stand down. He wrote:

Volunteers completely deceived. All orders for special action are hereby cancelled, and on no account will action be taken.

This order was delivered to units across the country by the O’Rahilly and others, and MacNeill also placed an ad to that effect in the Sunday Independent. However, the IRB decided to go ahead anyway; their only concession was to delay the start by one day until Easter Monday. It meant the Volunteers received conflicting orders with the effect that only about 1,300 took part, almost exclusively in Dublin.

There were about another 200 from Irish Citizen Army plus perhaps a hundred more from IRB and other groups, including the women’s organisation Cumann namBan, which provided support services.

This was no match for the British Army and the Easter Rising was put down within six days.

Role of the Volunteers after the Easter Rising

The leaders were executed but most of the Volunteers survived to take part in the Anglo-Irish War, or Irish War of Independence. In fact, it was members of the Volunteers, including Seán Treacy and Dan Breen, who fired the first shots in the war when they killed two police officers in Co Tipperary.

During the war, the Volunteers were increasingly referred to as the Irish Republican Army or IRA.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty that ended the War of Independence split the Volunteers, with up to 80% opposing it. Those who supported the treaty joined the new Free State Army formed by Michael Collins and became known as the Regulars.

Many of those who opposed it were known as the Irregulars and started to fight against their former colleagues during the Civil War. Although they lost, many of them never accepted the legitimacy of the Irish Free State and continued to oppose it as members of the IRA.

The IRA remained active for the next 50 years, mounting sporadic bombings and shootings as part of its opposition to the partition of Ireland and the creation of the Northern Ireland state. They staged the Border Campaign in the late 1950s, which involved bombing targets along the border.

They also blew up Nelson’s Column in Dublin, regarding as an offensive reminder of British imperialism at a time when Ireland was about to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising.

The organisation was falling into stagnation at that time but was revitalised as the Troubles emerged out of the Civil Rights Movement in Northern Ireland at the end of the 1960s and into the 1970s. It declared an end to its military campaign in 1994 as part of the Peace Process. It later decommissioned its weapons and agreed to play no further part in any paramilitary activity.