The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) was a secret organisation dedicated to establishing a democratic republic in Ireland, by violent means if necessary. It staged the Fenian Rising of 1867 and masterminded the 1916 Easter Rising.

The IRB was formed on St Patrick’s Day, 17 March in 1858 by the former Young Irelander, James Stephens, with the support of Irish exiles and sympathisers in the United States who provided much of the early funding. That same year, a similar organisation called the Fenian Brotherhood was set up in America by another Young Irelander and friend of Stephens, John O’Mahoney. The two groups worked together and collectively were often referred to as the Fenians. O’Mahoney had taken the name from the Fianna, a mythical band of Irish warriors.

Some of the IRB’s most prominent members included Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa and John Devoy. O’Donovan Rossa had set up the nationalist group, the Phoenix National and Literary Society. This was absorbed into the IRB when O’Donovan Rossa joined in 1861. He later went on to become one of the organisation’s most militant and outspoken members.

John Devoy was appointed Chief Organiser of the Fenians in the British Army. His mission was to persuade Irish troops in the British Army to desert. By 1866, he claimed that he had 80,000 men ready to join him in a rebellion. However, the British discovered his plans and Irish regiments were moved out of Ireland to duties abroad and replaced with regiments from England.

IRB wanted democracy and equality for all

The guiding principles of Fenianism were that Ireland had an incontrovertible right to be an independent nation and that such independence could only be achieved by armed rebellion because Britain would not give up control voluntarily. They believed in democracy and equality for all. These seem fairly uncontroversial ideas by today’s standards but they were considered radical and dangerous by the ruling classes in 19th century Britain.

The IRB set up as a secret organisation and required new members to swear allegiance. The oath went through various drafts before it was settled as:

‘In the presence of God, I (insert name) do solemnly swear that I will do my utmost to establish the independence of Ireland, and that I will bear true allegiance to the Supreme Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Government of the Irish Republic and implicitly obey the constitution of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and all my superior officers and that I will preserve inviolable the secrets of the organisation.’

The IRB was denounced by the British government and press as might be expected, but it also drew widespread criticism in Ireland. The Catholic Church disliked its readiness to use force, and its democratic and republican ideals. The Bishop of Kerry, David Moriarty, was so incensed by the IRB’s policies that he wrote in the Irish Times: “When we look down into the fathomless depth of this infamy of the heads of the Fenian conspiracy, we must acknowledge that eternity is not long enough, nor hell hot enough to punish such miscreants.”

The IRB was behind several plots, bombing campaigns and attempted rebellions from the 1860s onwards.

It planned to stage a rebellion in 1865 but the British discovered the plans and moved quickly to stop it before it could even begin. The IRB newspaper, the Irish People, which had been infiltrated by British informants, was shut down. Many IRB leaders including O’Donovan Rossa and Stephens were arrested and imprisoned. Stephens later escaped with the help of John Devoy.

The British tried to clamp down by arresting anyone suspected of being involved in the IRB. It also tried to choke its supply of funds by seizing money sent from America. The IRB was shaken by the failure of its plans and needed to respond quickly. Together with the Fenian Brotherhood, it planned to use Irish soldiers who had fought in the American Civil War to stage a rebellion in Ireland.

American Civil War and the Fenian Rising of 1867

The Fenian Rising of 1867 began on 5 March. The nominal leader was James Stephens but he was now exiled in France. Thomas Kelly, a veteran of the American Civil War, was in command. The plan, drawn up by another Civil War veteran, General Millen, was to stage guerrilla warfare targeting key strategic sites, particularly in Dublin.

There would be other targeted outbreaks across the country. Meanwhile, several thousand men – some estimates say as many as 7,000 – were sent to Tallaght outside of Dublin. Their role was not so much to fight but to act as a decoy to draw British troops out of Dublin, leaving it effectively unguarded. Unfortunately for the IRB, due to lack of arms and poor communications, the plan never really got off the ground. As was so often the case, infiltrators had tipped off the British who sent in reinforcements in readiness.

The rebellion descended into isolated skirmishes that were easily put down. The Battle of Tallaght as it came to be known was over within a day. The rebels lacked both training and weapons and many were dispersed after police opened fire. The rest left that night when it became apparent that the planned uprising had stalled. Twelve people were killed in the Tallaght shootings, including eight rebels.

From a military perspective the 1867 Fenian Rising was a failure but it was still a significant event because it showed that the desire for Irish independence was still strong, even if that desire could not be translated into effective military action. There was also great symbolic value in that James Stephens declared an Irish Republic with these words:

“Our rights and liberties have been trampled on by an alien aristocracy, who, treating us as foes, usurped our lands and drew away from our unfortunate country all material riches. We appeal to force as a last resort… unable to endure any longer the curse of a monarchical government, we aim at founding a Republic based on universal suffrage, which shall secure to all the intrinsic value of their labour.

The soil of Ireland, at present in possession of an oligarchy, belongs to us, the Irish people and to us it must be restored. We declare also in favour of absolute liberty of conscience and the separation of Church and State. We intend no war against the people of England; our war is against the aristocratic locusts, whether English or Irish, who have eaten the verdure of our fields.”

Declaration of independence foreshadowed Proclamation

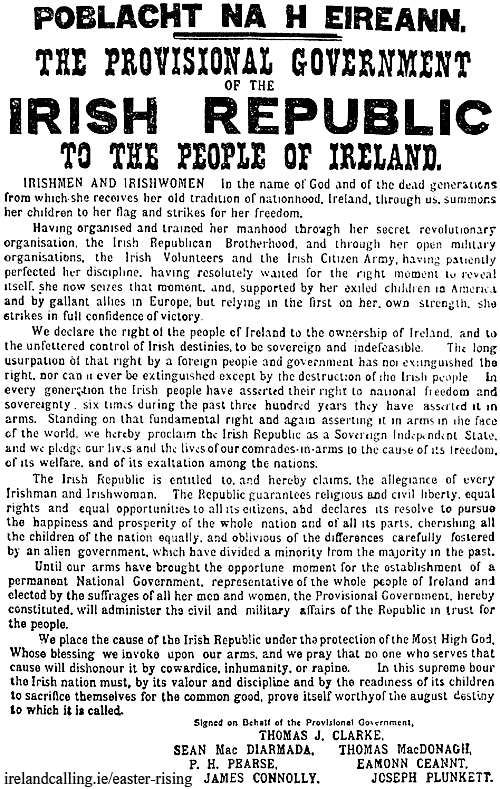

These words were to be an inspiration to succeeding generations of nationalists, including of course, the IRB Military Council who signed the Proclamation of the Irish Republic during the Easter Rising of 1916. The final sentence was of particular relevance to one of the Easter Rising’s leading figures, James Connolly, who as a passionate socialist was not only fighting for Irish independence, but to liberate the working class of Ireland.

Guerilla warfare and the London dynamite campaign

At its height, the IRB had between 40,000 and 50,000 members but this started to decline due the failure of the rebellion together with internal divisions over direction and control. One of the points of contention involved the use of guerrilla warfare.

Irish American Fenians including Jeremiah O’Donovan Ross and Tom Clarke, who both settled in the United States for a time, recognised that they could not muster enough troops to take on the British Army and so favoured terrorist bombings. These were designed to inspire fear and sway British public opinion into thinking that Ireland was not worth holding on to and should be given back to the Irish.

They believed this guerrilla campaign in England should take place at the same time as plans for a new and better organised rebellion continued in Ireland. Many Fenians were disgusted at the idea and considered it ignoble to fight in this way. James Stephens described it as “the wildest, the lowest and the wicked conception of the national movement”.

Nevertheless, the Dynamite Campaign as it came to be known went ahead and lasted from January 1881 to 1885. Explosions were carried out at several sites in London including the Tower of London and the Houses of Parliament. They had the desired effect of causing fear and panic, but the British establishment did not budge.

A total of 20 Fenians were arrested, including Tom Clarke who was sentenced to 15 years imprisonment.

IRB, Home Rule and the New Departure

While the Irish American Fenians were engaged in the bombing campaign, the IRB in Ireland had aligned itself for a time to the Home Rule movement led by Charles Stewart Parnell. It agreed an arrangement called the New Departure. The IRB was to provide funds and lend its organisational skills to the campaign in return for a say in policy.

Its key demands were that Parnell’s Irish Parliamentary Party should insist on Irish self-government and should press for legislation giving Irish tenant farmers ownership of their land. Following the Land War, in which landlords who evicted tenants were attacked, intimidated or boycotted, the Land Act was passed in 1881. It gave the tenants the three F’s that they wanted: fair rents set by independent tribunals, fixity of tenure so they couldn’t be evicted if they kept up with the rent and free sale so they could sell on their tenancy if they wished.

The IRB played no official role in the Land War. However, many of its members took part on an individual basis using their organisational skills to oppose evictions.

In 1882, the IRB suffered a split when a radical faction broke away to form the Irish National Invincibles. They murdered the Chief Secretary for Ireland Lord Cavendish and his secretary in what became known as the Phoenix Park Murders.

The murderers were caught and hanged but the incident outraged public opinion and damaged the image of the IRB and the wider nationalist movement.

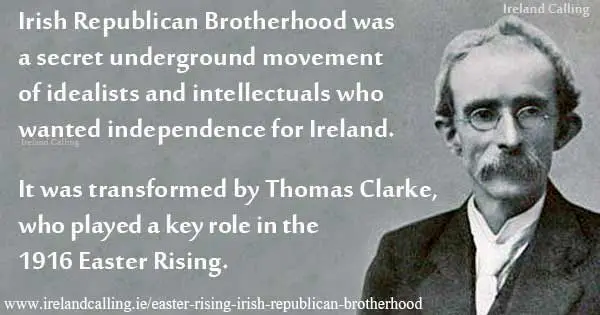

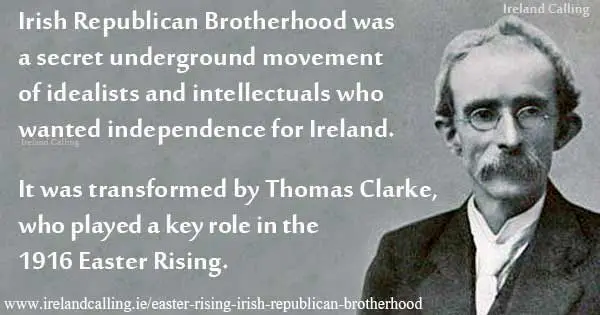

By the early 20th century, the IRB appeared a spent force, weakened by splits and disputes over tactics. It had also lost some of its more moderate supporters to the Home Rule campaign. Its numbers had dwindled to below 2,000 and it was dependent for funds on its American counterpart, Clan na nGael, the organisation that had followed on from the Fenian Brotherhood in 1870.

Infiltrating the Volunteers and divisions over the Easter Rising

By 1910, however, things were beginning to change. Tom Clarke had returned from America. He set up a tobacconist shop in Dublin but he still fostered hopes of rebellion and an independent Ireland. Meanwhile, a new generation of nationalists was emerging who thought the IRB could still provide a structure to fight for Irish independence. Some of the most notable included Bulmer Hobson, Denis McCullough and Sean MacDiarmada.

Hobson set up a newspaper called Irish Freedom. Together with McCullough he formed the Dungannon clubs, societies that promoted the idea of Irish independence. They also tried to persuade Irishmen not to enlist in the British Army and to join the IRB instead. Hobson and MacDiarmada moved from Belfast to Dublin and teamed up with Clarke.

In 1913, the Irish Volunteer Force was formed to provide the Home Rule campaign with military support if needed. An estimated 160,000 men had joined the Volunteers by 1914. The IRB realised very quickly that these Volunteers could provide the foot soldiers to support a successful rebellion.

They began recruiting prominent Volunteers including Patrick Pearse, Joseph Plunkett, Éamonn Ceannt and Thomas MacDonagh.

They began planning a rebellion after the outbreak of the First World War. They saw Britain’s difficulty as Ireland’s opportunity. In January 1916, they became aware that the leader of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, James Connolly, was planning a rebellion of his own using the Irish Citizen Army (ICA). This was a paramilitary group set up to protect trade unionists from police brutality during strikes and union demonstrations.

They persuaded Connolly to join forces with them and become a member of the IRB’s Military Council which would now be made up of seven men: Tom Clarke, Patrick Pearse, Seán MacDiarmada, Éamonn Ceannt, Thomas MacDonagh and finally, James Connolly.

These seven men planned and carried out the 1916 Easter Rising and proclaimed Ireland to be an independent republic. All were later executed when they were forced to surrender after six days of fighting.

The legacy of the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The IRB survived the Easter Rising and continued under the leadership of Michael Collins. However, many members including Éamon de Valera and Cathal Brugha left as they felt it was redundant; its role having been taken over by the Irish Volunteers.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty, which was signed by Michael Collins and others to end the War of Independence, proved as divisive in the IRB as it did in all nationalist groups. However, its Supreme Council voted by an 11-4 majority to accept it.

The IRB played no part in the Civil War and ceased functioning as an organisation in 1924.

The IRB’s main legacy is the 1916 Easter Rising, for although it failed militarily, it had a form of success in the end. The executions of the leaders outraged public opinion, which had been hostile to the Rising at first. It led to a wave of nationalist feeling which manifested itself in the overwhelming success of the pro-independence party Sinn Fein in the 1918 General Election.

They won the vast majority of seats and the Home Rule supporting Irish Parliamentary Party was wiped out. It gave the nationalists a mandate from the people as they entered into the War of Independence, which eventually led to the Irish Free State and eventually to the Irish Republic.

easter-rising.html