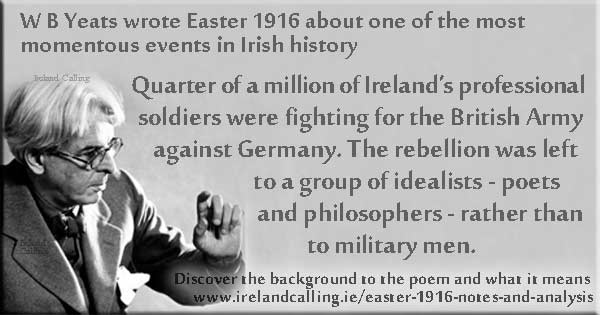

Easter, 1916 by W B Yeats is set in the aftermath of the Easter Rising of 1916, when a small group of Irish nationalists led a rebellion to overthrow British rule and establish an independent Ireland.

It was a strange kind of rebellion. Ireland’s professional soldiers – a quarter of a million of them – were fighting for the British Army against Germany. The rebellion was therefore left to a group of idealists. – poets and philosophers – rather than to military men.

It was quickly put down and looked to be a complete failure – a “casual comedy” as Yeats put it. Yet, in spite of this, it went on to become a turning point in Irish history.

Irish public opinion was largely hostile to the rebellion at first, but that changed when the leaders were executed. The executions were seen as a brutal overreaction and turned Irish opinion against Britain and in favour of the Nationalists. In this way, as Yeats puts it, a “terrible beauty is born”.

Easter, 1916 gives Yeats’ view of the rebels from the days before the Rising and relates how those views changed afterwards.

First stanza – a terrible beauty is born

The structure of Easter, 1916 spells out the date the rebellion began, April 24, 1916. There are 16 lines in the first and third stanzas, and there are 24 lines in the second and fourth stanzas. There are also four stanzas representing April, the fourth month of the year.

Most of the leaders were prominent in Irish Nationalist circles. In the opening, Yeats tells of how he would sometimes chance to meet them on the street as they came out of work. They had “vivid” faces, perhaps hinting at the energy and idealism to come.

Yeats would have known most of them personally having dabbled in Nationalist politics himself as a young man. He would therefore stop and exchange pleasantries or “polite meaningless words” but he did not take them seriously.

Indeed, he would be just as likely to mock them and tell amusing stories about them when he met his friends later in his club.

He thought that he and the rebels only lived where “motley” is worn, that is a reference to clothes of any colour without any particular significance or belief. This contrasts with the idealism summed in the phrase “wherever green is worn” at the end of the poem.

Easter, 1916

I have met them at close of day

Coming with vivid faces

From counter or desk among grey

Eighteenth-century houses.

I have passed with a nod of the head

Or polite meaningless words,

Or have lingered awhile and said

Polite meaningless words,

And thought before I had done

Of a mocking tale or a gibe

To please a companion

Around the fire at the club,

Being certain that they and I

But lived where motley is worn:

All changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

That woman’s days were spent

In ignorant good-will,

Her nights in argument

Until her voice grew shrill.

What voice more sweet than hers

When, young and beautiful,

She rode to harriers?

This man had kept a school

And rode our wingèd horse;

This other his helper and friend

Was coming into his force;

He might have won fame in the end,

So sensitive his nature seemed,

So daring and sweet his thought.

This other man I had dreamed

A drunken, vainglorious lout.

He had done most bitter wrong

To some who are near my heart,

Yet I number him in the song;

He, too, has resigned his part

In the casual comedy;

He, too, has been changed in his turn,

Transformed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

Hearts with one purpose alone

Through summer and winter seem

Enchanted to a stone

To trouble the living stream.

The horse that comes from the road,

The rider, the birds that range

From cloud to tumbling cloud,

Minute by minute they change;

A shadow of cloud on the stream

Changes minute by minute;

A horse-hoof slides on the brim,

And a horse plashes within it;

The long-legged moor-hens dive,

And hens to moor-cocks call;

Minute by minute they live:

The stone’s in the midst of all.

Too long a sacrifice

Can make a stone of the heart.

O when may it suffice?

That is Heaven’s part, our part

To murmur name upon name,

As a mother names her child

When sleep at last has come

On limbs that had run wild.

What is it but nightfall?

No, no, not night but death;

Was it needless death after all?

For England may keep faith

For all that is done and said.

We know their dream; enough

To know they dreamed and are dead;

And what if excess of love

Bewildered them till they died?

I write it out in a verse—

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

Easter, 1916 – Main characters