The 1798 Rebellion was a major event in the history of Ireland, even though it failed. A group of Irish nationalists became inspired by the French and American Revolutions, and rose up to fight for their independence.

However, the rebels were disorganised and lacked a clear command structure. The rebellion was ultimately defeated by the British Army. Despite the defeat, the rebellion set a tone in Ireland. It paved the way for several more rebellions throughout the 19th century, and eventually the Easter Rising, War of Independence and Civil War.

Society of United Irishmen

The build-up to the rebellion started with the formation of the Society of United Irishmen, a political movement led by Theobald Wolfe Tone and Henry Joy McCracken amongst others. They hoped to unite the Catholics and Protestants in Ireland to form a strong political movement aiming to improve conditions.

They had been inspired by the American and French Revolutions, and had political links in France. When Britain went to war with France, the United Irishmen were driven underground. The group soon began plotting an uprising against the British.

Britain began to take threat seriously

Wolfe Tone and other United Irishmen leaders travelled to France to try and gain military support. A fleet of 14,000 French soldiers were recruited but they failed to complete the journey to Ireland after bad weather forced them to turn their boats around.

The British authorities found out about the planned rebellion and sent spies out to identify and arrest any United Irishmen leaders.

Wolfe Tone was forced to stay in France, and continued to try and gain support for the Irish cause.

The uprising went ahead without help from the French

A plan for an uprising was formed with the Dublin United Irishmen seizing the mail coaches leaving the city on the evening of the 23rd May. That would be the signal for all other branches of the United Irishmen to rise up in their own cities. The mail coaches were seized, but the Dublin leaders decided not to go ahead with the rebellion until military support from France had arrived. However, the rebels in the south of the country went ahead and began attacking British forces and gaining control of the cities.

This statue of Wolfe Tone at Bantry, looking out to sea, is symbolic of hope for French help, rather than literal portrayal of where Tone was at any precise moment.

Dozens of United Irishmen leaders were executed

Most outbreaks were quickly quashed by the government forces in places such as Kildare, Wicklow, Carlow and Meath. The lack of action from the Dublin rebels meant the British Army were not being overstretched in dealing with the minor disruptions. Rebel leaders were captured and executed to dismantle the United Irishmen organisation and deter others from entering into battles. British soldiers patrolled through major cities, torturing any United Irishmen suspects and burning their homes and businesses. It seemed the government had stopped the rebellion from gathering any momentum.

Victory at Oulart re-ignited the rebellion

However, a group of United Irishmen in Wexford were seriously bucking the trend. They were led by a Catholic priest named Father John Murphy. He had initially urged his parishioners not to take up arms against the British, but changed his opinion when a group of soldiers tried to intimidate the villagers by burning down houses in the hunt of rebels. A minor conflict led to the death of two of the soldiers.

The townspeople gathered at Oulart Hill, knowing that the government forces would be returning with reinforcements and hungry for revenge. Father Murphy led the Wexford rebels to a successful battle which resulted in the death of more than 100 British soldiers. The battle shocked the authorities at Dublin Castle who had not anticipated such military prowess from the Wexford rebels.

In the following days, Father Murphy led his brigade of United Irishmen – now up to 15,000 strong – in the storming of Wexford city. These victories gave hope and boosted the morale of United Irishmen across the rest of the country.

Northern rebels ousted leaders

Northern rebels ousted leaders

Many United Irishmen in the north of Ireland were growing restless and frustrated at the lack of action in their areas. The leaders that still wanted to wait for the French were ousted and that policy was abandoned.

Morale sapping defeat at Antrim

Henry Joy McCracken took control of the Antrim rebels. About 4,000 tried to take the city of Antrim, and a long and error-strewn battle took place. Initially, the rebels cleverly lured the British soldiers towards them after appearing to retreat. However, more rebels were hidden in side streets and houses and ambushed the British.

The rebels forced the British back and attempted to seize control of the city’s castle. More British troops arrived and managed to fend off the attack. Despite a promising start to the battle, the United Irishmen had been defeated. McCracken was arrested a few days later and executed after he refused to give up the names and activities of other United Irishmen leaders.

Poor leadership signalled end of rebellion in the north

Another group of Northern rebels were assembled by shopkeeper Henry Monro. They encountered a troop of British soldiers at Ballynahinch just outside Belfast on the 12th June. The British fired cannons from a distance but night soon fell and the battle was delayed with both sides holding their position. The rebels tried to persuade Monro to attack during the night but he refused considering it unchivalrous. Many slipped away in the night disillusioned by their leader’s decision.

The following day the battle did take place and the rebels suffered hundreds of casualties, with the conflict descending into a hunting and massacre exercise for the British. This defeat, coupled with the defeat at Antrim, signalled the end of the United Irishmen rebellion in the north of the country.

Monro escaped death on the battlefield but was betrayed by someone supposed to be hiding him and handed over to the authorities. He was hanged outside the front door of his home.

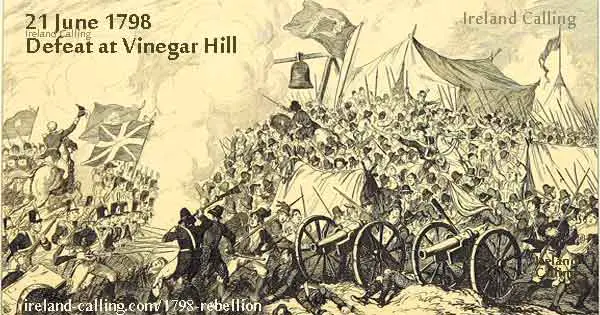

The Battle of Vinegar Hill

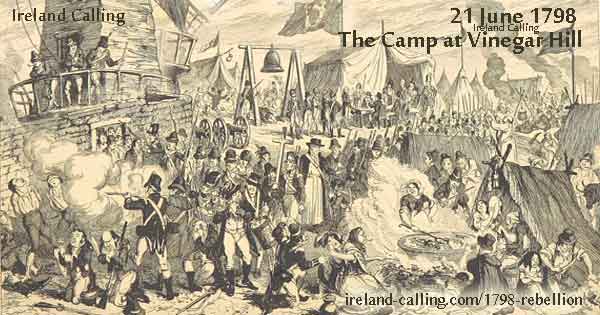

The Wexford rebels led by Father Murphy had also suffered some heavy defeats to the British Army notably at New Ross and Arklow where they lost 2,000 and 1,000 men respectively. They had been entering battles in small units and being defeated.

It was decided that all Wexford United Irishmen unit should gather at Vinegar Hill for one ultimate battle against the British. They did this and there were an estimated 20,000 in total.

The British Army, led by General Gerard Lake, had an instruction to crush the spirit of the Wexford rebels, as had been done to those in the north. The Army was also better equipped than the rebels, and equal in number. They surrounded the hill with the plan to attack from all sides leaving no way of escape for the rebels.

They fired cannons and gunshots at the rebels, who were lambs to the slaughter with most armed only with pikes. The battle lasted about two hours and hundreds of United Irishmen were killed.

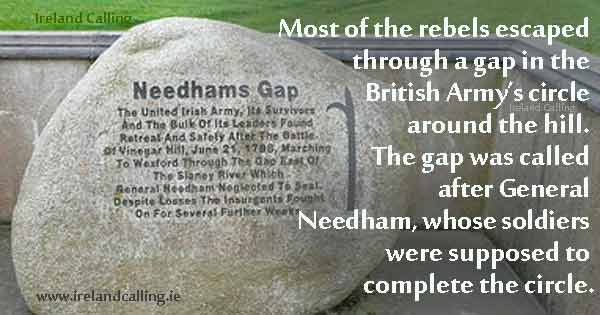

Most of them did manage to escape through a small gap in the British Army’s circle around the hill. The gap was called “Needham’s Gap” after General Needham, whose troop of soldiers was supposed to complete the circle.

Execution of Father Murphy

Father Murphy was captured a month or so later. He was stripped, flogged and hanged. His head was cut off and placed on a spike, and his corpse burnt in a barrel of tar opposite a Catholic church. The British soldiers forced the Catholics in the area to open their windows so they could smell the burning corpse of Father Murphy.

The escaped rebels mostly fled into the Wicklow mountains, and although some continued to fight in small groups, the British had taken back Wexford, the last remaining rebel stronghold. The rebellion was over.

Late arrival of French forces too little too late

A little over two months later, a troop of 1,100 French soldiers finally arrived in Ireland. They were led by General Humbert, a veteran of the French Revolution. Unfortunately, by the time they arrived, the United Irishmen had already been defeated. Humbert joined his troop with a remaining Irish rebel group and they were victorious in defeating the British Army at Castlebar in County Mayo. They briefly claimed an independent republic of Connaught but surrendered under the threat of the superior British Army.

Humbert and his French soldiers were treated as prisoners of war but the United Irishmen fighting with them were massacred.

Atrocities of United Irishmen and British Army

The United Irishmen rebellion had ended. It lasted just four months but saw the deaths of an estimated 10,000 Irish rebels and 600 British soldiers.

Throughout the rebellion there were merciless killings and horrendous atrocities carried out by both sides. Many of the United Irishmen that were captured were tortured for information before being violently executed. The British soldiers were also known to go on killing sprees through villages, with beatings, rapes and tortures occurring in extreme cases.

The rebels were guilty of equally heinous crimes. In one revenge killing following a defeat in battle, they trapped more than 100 Protestants in a barn and set it alight. The rebels reportedly stood guard to make sure no-one escaped, even piking a young boy to death as he tried to slip through a hole in the wall.

Ireland was left firmly under Britain’s control

The result of the 1798 Rebellion was that Britain removed the Irish parliament, and the Union of Great Britain and Ireland was formed in 1801. This was deeply unpopular with the Irish republicans, but they had failed in their rebellion, and ended up with less political freedom.

1798-rebellion.html”]