Paul Cullen was the one of the most influential men in Ireland’s history and the first Irishman to become a cardinal. He was the driving force that made the Catholic Church all powerful throughout the country from the second half of the 19th century onwards.

The foundations he laid were so strong that the authority of the Church was not challenged or diminished until the child sex abuse scandals of the 1990s. It meant that for most of the 20th century, the Church wielded more power in Ireland than in virtually any other European country.

No Irish politician could hope to succeed if he antagonised the clergy and no major policy could be adopted if the Church opposed it. Many people consider that this gave Ireland a strong moral core; others contend that it held the country back economically and socially. Whether for good or bad, it was Cardinal Cullen more than anyone who made it happen.

Paul Cullen was born on 29 April, 1803 at Narraghmore in Co Kildare. He was the youngest of 16 children born into a prosperous farming family. He was a gifted scholar and excelled so much in his studies at St Patrick’s College in Carlow that he was invited to continue his education at the Pontifical Urban College in Rome, which was to have a huge influence on his life.

As wealthy farmers, the Cullen family distrusted Irish revolutionaries and agitators for reform of land ownership. This was another influence that was to remain with Cullen throughout his career.

Cullen graduated as a Doctor of Divinity and was ordained as a priest in 1829. During his time in Rome, he became a strong believer in ultramontanism, which emphasised the central authority of the Pope. It was a belief he promoted for the rest of his life.

He rose rapidly to prominence in Rome and became Rector of the Irish College and the College of Propaganda. He was then appointed Bishop of Armagh on 19 December, 1849 and Bishop of Dublin on 1 May 1852.

He reached the pinnacle of his career when he became a cardinal on 22 June, 1866, the first Irishman to hold that position.

Cullen used all his skill and energy to centralise the power of the Catholic Church in Ireland and make it subordinate to Rome in all matters.

Ireland was already a fervently Catholic country when Cullen returned as Bishop of Armagh in 1849. However, although it acknowledged the supremacy of Rome and the Pope, local clergy still retained their own ways and customs. It meant practices and even beliefs could vary across the country.

Cullen set about changing all that. In 1850, at Rome’s request, he organised a national synod at Thurles in Co Tipperary. It was the first such event since the 12th century and the first national meeting of bishops for two centuries.

The synod issued a number of decrees to increase discipline and uniformity throughout the church in Ireland, and more importantly, to ensure that all disputes about doctrine, customs or practices should be referred to Rome. This weakened the discretionary authority of individual bishops and ensured only practices approved by Cullen and Rome could be followed.

Traditional practices such as gatherings at shrines and services in private homes were discouraged as they were outside central control. Instead, Catholics were told they must attend Mass at church every Sunday, go to confession regularly and take communion – all practices that brought them in line with the thinking at Rome. Cullen introduced the custom of priests wearing the Roman collar and being called Father, instead of Mr, thus making them stand out from ordinary people and giving them a greater sense of authority.

It was turning religion from an amateurish, localised affair into a highly centralised corporate structure that allowed no room for discretion or personal interpretation. It followed, therefore, that the only way to salvation was to forego personal beliefs and submit to the authority of Rome and the Pope. People had to worship in places and at times decreed by the Church.

Cullen was the enthusiastic architect of this approach and it gave the Catholic Church enormous power and influence over the Irish people, to the point that many feared and respected the local priest far more than any policeman or judge. This power lasted until well into the 1980s and was only broken when the child abuse scandals of the 1990s made people question the established order and in many cases, reject it.

Cullen firmly believed the Church should be at the heart of everything, including education. He abhorred the secular schools, which he regarded as ‘godless colleges’. His opposition helped to defeat the Irish Universities Bill in 1873, because it proposed non-sectarian education and would give no special priority to Catholicism. He preferred to promote the Catholic University of Ireland, which he had set up in 1854, with Daniel O’Connell being one of its first students.

Cullen maintained close contact with Rome throughout his time as a cardinal in Ireland and helped formulate the principle of Papal Infallibility.

His desire to promote Church authority above everything else was one of the main reasons he was opposed to Irish nationalist organisations like the Young Irelanders, and the Fenians who came to prominence in the 1860s and staged an unsuccessful rebellion. The Fenians advocated the overthrow of British rule through violence, which, of course, the Church could not support.

One other important factor, however, was that the Fenians were a secret organisation which put them outside the Church’s authority. Cullen was not in favour of British rule but if there was to be any opposition to it, he wanted to be the one in control. He preferred to pursue change through constitutional means and lobbied the government on a regular basis.

The political unrest caused by the Fenians and the agrarian reform movement prompted the British Prime Minister, William Gladstone, to offer reforms in order to quell unrest. This led to the disestablishment of the Protestant Church of Ireland, which only represented about the 12% of the Irish population. In 1873, the ban on Catholics attending the Protestant Trinity College Dublin was lifted.

These were important concessions that benefited the Catholic Church, but they were won by secular groups rather than the Church itself, although Cullen’s frequent lobbing may have played a part.

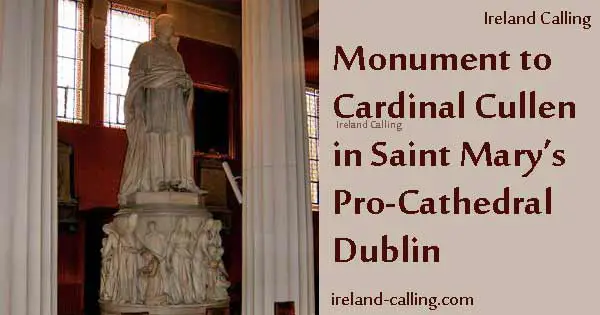

Cardinal Cullen died on 24 October 1878 in Dublin. He is buried at Holy Cross College in Drumcondra.

His legacy was to mould the Catholic Church in Ireland into a highly organised, highly centralised machine that still dominated Irish life a century after his death. Whether that influenced was always for the good has been questioned by many commentators, but there is little doubt that it owed its origins to Cullen’s work.

Paul Cullen – architect of Catholic Church dominance in Ireland