Henry Grattan was born in Dublin on 3 July 1746. He was a key figure in Irish politics during the late 18th century. Grattan, entered the Irish parliament in 1775, and quickly became leader of the National Party. Grattan was a member of the Church of Ireland, but was sympathetic to the Irish Catholics. At the time, almost all senior positions in Irish society were held by Protestants.

British soldiers sent to fight in American Revolution

Britain was facing a revolution in America, with several colonies uniting and uprising in what became the American Revolution. This caused Britain great problems and they withdrew all their soldiers who were stationed in Ireland and sent them to America to fight. Grattan took advantage of the British weakness, and built his own army of Irish Volunteers.

Grattan built army of 40,000 Irish Volunteers

Grattan pressed the British government to repeal its unfair trade laws on Ireland. The British government weren’t able to contend with Grattan at this time, especially as he had built an army of more than 40,000 men. They relented to his demands.

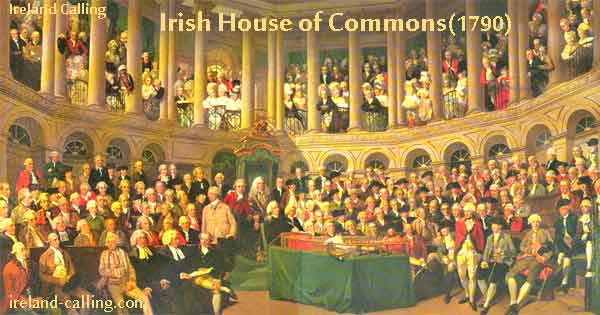

However, Grattan knew that to gain total control of Ireland, an independent Irish parliament must be achieved. After Britain lost the war in America Grattan acted. He demanded an independent Irish parliament. The British government lacked the spirit and finance to face another revolution and granted Ireland its own parliament in 1782.

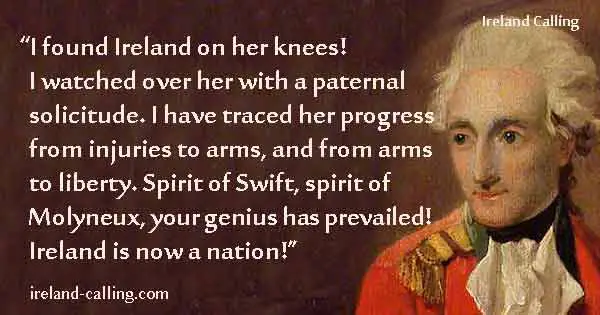

Grattan announced the news to thousands of supporters in Dublin with the following speech.

“I found Ireland on her knees! I watched over her with a paternal solicitude. I have traced her progress from injuries to arms, and from arms to liberty. Spirit of Swift, spirit of Molyneux, your genius has prevailed! Ireland is now a nation!”

He was rewarded with a parliamentary grant of £100,000. He refused to accept it until the sum was eventually halved.

Ireland still under British rule

Grattan had achieved an independent Irish parliament but unfortunately it was still ultimately under British rule. The landowners and officials all across Ireland were still loyal to Britain. All the major authority positions such as The Lord Lieutenant of Ireland were still appointed in London. The British had kept hold of their control over Ireland. They could even make changes to Irish law themselves without even consulting the Irish parliament.

However, the Irish parliament was a step forward for the country, and many of these underlying corruptions were not known at the time. Grattan set about his work running the country.

Grattan worked towards democracy

Grattan wanted to run a democratic country but knew that such a reform would not go smoothly. More than two thirds of the population were Catholic, but almost none owned land. Grattan knew that to allow every person in the country the vote would end with riots. The Catholic peasants would try to oust the Protestant regime, but the Protestants held all the power because of their superior wealth. Grattan tried to address this issue on a gradual basis. In 1792 he allowed Catholics to stand for election and take a seat in the House of Commons, but only if they were landowners.

R. B. McDowell wroted of Henry Grattan in his book, ‘The Protestant Nation’ (1775–1800):

‘Grattan is a superb orator – nervous, high-flown, romantic. With generous enthusiasm he demanded that Ireland should be granted its rightful status, that of an independent nation, though he always insisted that Ireland would remain linked to Great Britain by a common crown and by sharing a common political tradition.’

Wolfe Tone and Fitzgerald rallying the Irish

The legislation was met with hostility in Ireland. The country was beginning to stir with feelings of revolution. Irish nationalists such as Theobald Wolfe Tone and Lord Edward FitzGerald were rallying the Irish public after being inspired by the recent American and French Revolutions.

Grattan tried to warn the British government, with whom he had maintained a mutually respectful working relationship, that the feeling in Ireland was one of rebellion. The United Irishmen organisation had swelled in numbers and unless serious concessions were made to Ireland then an uprising would take place. The United Irishmen were made up of Catholics and also Protestants who were angry by the British treatment of the Irish people.

Grattan resigns in protest

The British government ignored Grattan’s pleas, so he resigned from his post in protest. He sent an open letter to the people of Ireland explaining his position and attacking the actions of the British government.

The United Irishmen were initially waiting for military support from France before uprising, but when that support was delayed they went ahead on their own.

He died on 6 June 1820, and was buried in Westminster Abbey. Soon after Grattan’s death, Sydney Smith (an English wit) said:

“No government ever dismayed him. The world could not bribe him. He thought only of Ireland; lived for no other object; dedicated to her his beautiful fancy, his elegant wit, his manly courage, and all the splendour of his astonishing eloquence.”

1798-rebellion.html”]