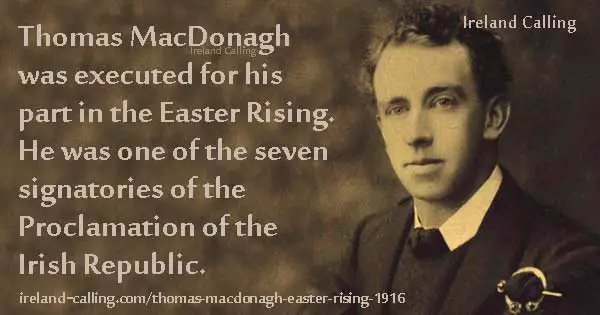

Thomas MacDonagh was a poet, academic and playwright who was executed for his part in the Easter Rising in 1916. He had only become a member of the Military Council planning the rebellion a few weeks before it began. He was one of the seven signatories of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic and a member of the Provisional Government. He wrote the Marching Song of the Irish Volunteers (see it here).

MacDonagh had no military experience but was in command of the Second Battalion of the Dublin Brigade of the Irish Volunteers during the Easter Rising and was stationed at Jacob’s biscuit factory.

MacDonagh was born in Cloughjordan in Co Tipperary on 1 February 1878. After leaving Rockwell College near Cashel he started working as a teacher in Kilkenny and Cork. In 1902 he published his first book of poems, Through the Ivory Gate.

He became a member of Gaelic League because of his interest in Irish culture and language. It was through his membership of the League that he began to associate with people like Patrick Pearse and Eoin MacNeill, who were leading nationalists and had a profound effect on him.

He met Pearse while on a visit to the Aran Islands. They became friends and MacDonagh started working at Pearse’s school, St Enda’s at Rathfarnham in Co Galway where he taught English and French, and became assistant head teacher.

MacDonagh’s first play featured rebellion

He later went on to gain an MA at University College, Dublin where after producing a thesis, Thomas Campion and the Art of Poetry, he became a lecturer in English at the university.

While in Dublin, he met Joseph Plunkett, who was also a poet and like MacDonagh would go on to sign the Proclamation and face execution.

The two men became close friends and started editing the Irish Review magazine together. MacDonagh also started to branch out as a playwright and his three-act tragedy, When the Dawn is Come, was staged at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin in 1908. Fittingly, perhaps, it was about rebellion.

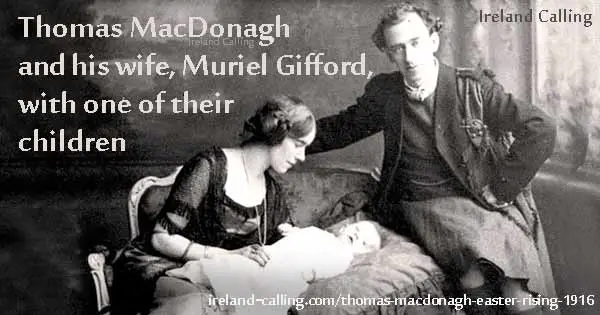

He married Muriel Gifford in January 1912 and they had two children.

MacDonagh was popular as a pleasant and charming character. Joseph Plunkett’s sister, Geraldine Plunkett Dillon wrote in her book, All in the Blood: “As soon as Tomás came into our house everyone was a friend of his. He had a pleasant, intelligent face and was always smiling, and you had the impression that he was always thinking about what you were saying.”

In 1914, he set up the Irish Theatre in Hardwicke Street together with Joseph Plunkett and Edward Martyn. They disapproved of the romantic approach of the Abbey Theatre and wanted to create more realism in drama.

MacDonagh’s nationalist views hardened as he got older

MacDonagh’s political views hardened as he got older. He had always had nationalist sympathies but had believed in change through peaceful and constitutional means. He was an active supporter of the Women’s Franchise League and became a member of the Dublin Industrial Peace Committee during the Lockout in Dublin in 1913.

Over the years, however, possibly though his association with people like Pearse, Plunkett and eventually Seán MacDiarmada, he began to think rebellion may be the only way to achieve independence for Ireland.

The three years before the Easter Rising saw his position hardening. He was one of the founding members of the Irish Volunteers and was appointed to its Provisional Committee. He then took a further radical step in 1915 by joining the Irish Republican Brotherhood, who were committed to achieving an independent Ireland by revolution if necessary.

Mary Colum, the wife of Páidric Colum, gives a clue to the hardening of his views in a comment she remembered him making shortly before the Rising. In her book, Life and the Dream, she wrote that he had told her: “This country will be one entire slum unless we get into action, in spite of our literary movements and Gaelic Leagues it is going down and down. There is no life or heart left in the country.”

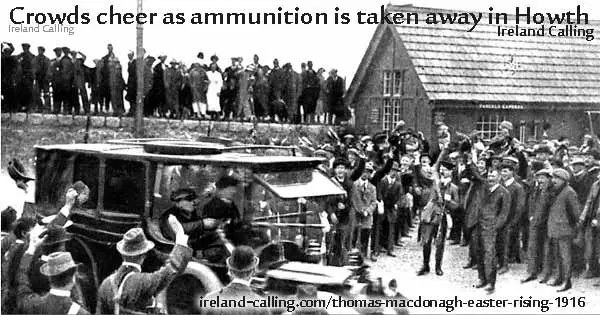

Howth gun smuggling to provide arms for Volunteers

MacDonagh was a late starter in terms of the Easter Rising but he rose rapidly to prominence. He was one of the main organisers of the Howth gun smuggling operation to provide arms for the Volunteers, and he wrote the Marching Song of the Volunteers.

He was angry with John Redmond, the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, for urging the Volunteers to enlist in the British Army at the outbreak of World War One. The call split the Volunteers, with most of them heeding Redmond’s call and enlisting. However, as many as 11,000 refused to go. These were the men who would provide most of the soldiers in the Rising. MacDonagh was appointed their Director of Training.

He furthered his reputation when Tom Clarke asked him to organise the funeral of the veteran Fenian Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa in 1915. The funeral was a huge event attended by more than 100,000 people and is now best remembered for the inspiring speech delivered by Patrick Pearse.

Independence might require ‘zealous martyrs’

Like Pearse and Seán MacDiarmada, MacDonagh began to believe that Irish independence might require a sacrifice from people willing to become “zealous martyrs”.

He was made Commandant of the Dublin Brigade of the Irish Volunteers and was drafted on to the IRB’s Military Council, the group planning the Rising, in early April 1916, just a few weeks before the rebellion started.

James Connolly replaced him as overall Commandant of the Dublin Brigade but he was still placed in command of the 2nd Battalion assigned to Jacob’s Biscuit factory, one of the largest sites chosen by the Military Council.

However, MacDonagh and his men saw very little action as the British largely ignored the factory to concentrate on more strategically important sites. MacDonagh surrendered on 30 April after receiving orders to do so from Patrick Pearse.

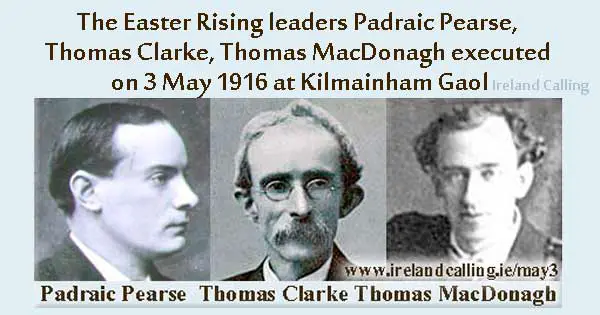

He was tried by court martial at Richmond Barracks and executed by firing squad on 3 May.

Poetic tribute: He shall not hear the bittern cry

MacDonagh’s work as a poet and playwright meant he had many literary friends, and some of them paid tribute to him in their writings. Francis Ledwidge, wrote was probably the best known tribute: Lament for Thomas MacDonagh.

MacDonagh’s wife Muriel died a year after his execution

Tragically, MacDonagh’s wife Muriel died of heart failure little over a year after his execution on 9 July 1917 while swimming to Skerries Island to plant the Irish flag, in defiance of the authorities. Her sister Grace married, Joseph Plunkett hours before he was executed for his part in the Rising.

Their children went on to become successful writers. Donagh became a poet and songwriter, and had plays performed on Broadway. Barbara wrote drama scripts for Radio Éireann, mostly under the name of her husband, Liam Redmond who was a popular actor during the 1950s.

Thomas MacDonagh’s life and work is celebrated at the Thomas MacDonagh Heritage Centre in Cloughjordan, Co. Tipperary. Various Gaelic Athletic Clubs are named after him, as are the MacDonagh Station and MacDonagh Junction shopping centre in Kilkenny.

easter-rising-signatories.html